The information below is the exact text of a letter from Jean van Schilfgaarde to Dr Jack Ford in 1992. Jack had contacted her for his research for his publication: Allies in bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two.

This is one of the few if perhaps the only personnel record of a civilian staff member of Camp Columbia during the Dutch occupation of the Camp. Jean worked at office of the Netherland Forces Intelligence service (NEFIS).

As she mentions several events that I have described in more detail elsewhere in the story, I have added links to those events and situations where appropriate.

Dear Jack,

I find it very interesting that you have chosen the Netherlands East Indies Government in exile for your thesis. I hope you will be able to glean some information from my experience of that time ea 1942-1945.

Sometime in 1942 there appeared in Swanston Street Melbourne many luxurious cars containing gold-braided naval personnel who we were told were the “Dutch”. Nothing so exotic had been seen on the streets of Melbourne before. They had come to take refuge here after the invasion of the Dutch territories by the Japanese. My first impression was that they must have a lot of money and that idea was enhanced throughout my association with them.

As my work with the Melbourne City Council was coming to an end and hearing through the Architects’ Institute that the “Dutch” were requiring staff I applied and became one of the first Australian recruits to work in a newly formed unit called Netherland Forces Intelligence Service NEFIS. This organisation was created by the Dutch Navy headed by Commander Salm and his objective was to supply information to the Australian Air Force in regard to Indonesia. At first, we worked in several houses in St Kilda Road and later in a very large house in Domain Road in South Yarra. My work along with others was drawing and annotating sketch maps and aerial photos with information which would be useful to the allies if raids were undertaken against the Japanese occupied territory in Indonesia. Gradually more Australians were employed including two women from the W.A.A.F. and two men from the Australian Air Force.

In July 1944 the whole set up of NEFIS was moved by special train to Camp Columbia at Wacol, a camp built by the Americans who had by this time moved further north. The huts were surrounded by trees and I was told well camouflaged from the air. The Dutch improved the wooden huts by putting showers and toilets in each one. They had new office buildings erected and expanded the club facilities – one for the officers and another for lower ranks. Civilians were welcome at both. After work we usually went to the club for a drink and social activities. A barbed wired fence was put around the female quarters and the gate locked at night. It was amusing to us Australians that a camp occupied by the Americans, who were known to have high standards of comfort for their camp, needed to be upgraded for the Dutch. The same high standard carried through to meals and services. We used to say jokingly that it was all being paid for by the sale of Queen Wilhelmina’s jewels and the gold bars that were brought out of Indonesia.

In answer to your question about political prisoners, the headman of Indonesian staff who waited on tables in the mess and whom I think we called “Mandrake” could have been one. I remember him very clearly, but I am not sure of his name. Someone told me he had been in prison but at the time I though it would been as a criminal. He had an air of superiority and even a little contempt especially when we tried to speak to him in Malay. He certainly was involved in the strike at the end of the war which I shall describe later.

Gradually more people were recruited to work at the camp from many parts of the world – flotsam and jetsam thrown up by the circumstances of war. The head of the department where I worked, which was called “Mapping Room”, was Hendrik van Schilfgaarde whom I married in January 1946. He with others had been working for the Shell company (Dutch) exploring for oil in Dutch New Guinea. They were evacuated to Darwin down through Central Australia to Adelaide and then Melbourne. They were in Darwin when it was bombed by the Japs. There were two American missionaries and a Canadian who had been in hitherto unexplored regions of Dutch New Guinea. Others were Swiss, Rumanian and a Jew who I knew well who had been working in England when war started so he could not go back to Holland. He was eventually reunited with his family and now lives in Melbourne. Another group were on the last planes which left Java and were attacked by Japanese bombers when they reached the Western Australian coast. One survivor, with whom I worked, described to me how the Japanese strafed the people in the water. Many died and he was shot in the leg. He married an Australian and now lives in Melbourne.

There must have been other accommodation provided in Brisbane but I cannot give you any details of this. Four bus loads of people used to come out of Wacol every morning and go back to Brisbane in late afternoon. Brenda Lewis was one of these and she lived at home with her parents.

I remember Dr. Van Mook and Dr. Van der Plas being at the camp at times but as far as I know they did not live there.

As to the allied and Government officials which you mention I have no knowledge of them ever visiting the camp maybe other sources could verify this.

As well as the Navy and Army personnel and the various European and Australian motley of civilians there were a number of Indonesian civilians, all male, evidently evacuated to be used as servants. Their quarters were at one end of the camp and sometimes at night we could hear the Gamelan Orchestra playing – a strange sound in the Australian bush. One day some distance from the camp I came on a group of Indonesians on top of a hill, all facing east praying to Allah. Not so surprisingly now but 50 years ago a strange sight. At their quarters in the camp many chooks could be seeing running around which proved a useful source of supply when feathers were needed for headdresses when they performed their dances.

I have said that the main arm of the Intelligence Service was to liaise and supply information to the Allies. There was another unit known as NEFIS 3. The activities of this unit were somewhat secret, but I know now that they were compiling information about dissidents in Indonesia. My husband told me later that they had a large file on Soukarno. I knew personally two Javanese sergeants who were dropped into the Japanese occupied territory to live as best they could and gather information. Months later they returned looking very tired and thin and would not speak much of their experiences. In the light of later events, I wondered if they were spying on their own people rather than the Japanese.

I don’t know of what value our work was to the Allies. They did bomb the oil fields at Balikpapan in Borneo, and I was told that information supplied by the NEFIS was used. Other people would be able to assess this better than I.

Australian – Dutch relations appear to be good at the military level, the Air Force lending a few low-ranking personnel and the Army providing two women drivers for high ranking Dutch army men. Socially the Dutch integrated very well. At another level whilst I was still in Melbourne some workers at the airport were critical that a separate car was sent to pick up individual officers instead of pooling. This at a time when petrol rationing was quite stringent. Post war the Dutch were resentful that they were prevented from getting their people back to Indonesia by the Communist dominated Unions. Maybe they blamed the Australian Government for not taking a stronger stance against the Unions.

In regard to racism between Australians and Indonesians there was none at all, many friendships being formed between the two nationalities. This was apparent when we had the concert of which I shall tell later. However, I was shocked at the division caused by the colour bar which appeared in many incidents involving Dutch and Indonesians. When we Australians arrived at the camp there was a large truck piled high with heavy luggage – we had come to stay for who know how long. There to greet us were some naval officers, Hendrik van Schilfgaarde (civilian) and two or three very small Indonesians (peasants). Hendrik helped with the unloading, but he told me later that the other Dutchmen would not be seen doing manual work with their “inferiors”. Throughout my stay at the camp, I watched with sadness the subtle division of brown and white, outwardly friendly but at times the line would be drawn which leads me to the concert. Brenda would have told you something of this because she took part in a quite spectacular way. Here is my story:- Indonesian night in Brisbane raised 300 for the NEI and Australian Red Cross. The evening was supported by Australian ladies from Camp Columbia. Collection Jean van Schiffgaarde Jack Ford.

The Indonesian in the camp were of many distinct races – inhabitants of Java, Celebes, Sumatra, Halmahera, Ambon etc. (all male). They needed a chorus of women for the Tari Piring dance so they invited some of the Australian girls to be trained and to take part – note that no Dutch girls were asked as they would surely have refused. Hendrik, our boss at the time, asked me to persuade the Australians not to take part as fraternising with the Indonesians, in his opinion, would surely lead to trouble. I laughed at this idea and the concert arrangements proceeded with great friendliness and enthusiasm. There was a man from Macassar, well educated, who remarked to me that it was very important that the concert should be a success because some of the Dutch were predicting that the Indonesians were not capable of organising such a big event.

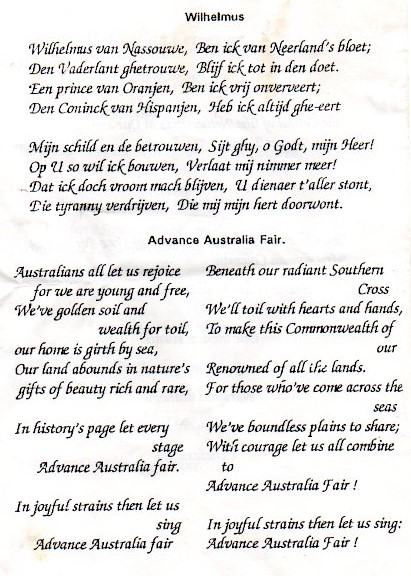

At the city hall in Brisbane on Wednesday the 18th of July 1945 the concert took place before an audience of 2000 and 300 pounds raised for the Red Cross. The Australian girls performed the lighted candle dance with great distinction with a native of Sumatra as the sole dancer. It was a cultural event the like of which had not been seen before in Australia. Did Brenda give you a copy of the program? If not, I can supply one.

When Holland was liberated in 1945 a number of people were brought to Australia and came to live in the camp. I remember some resentment from the Dutch girls against us Australians because they had suffered such hardship during the German occupation, whereas we had been living in comparative luxury paid for with Dutch money. Soon after that, when Japan capitulated came a number of Eurasians from Indonesia from Indonesia and they were still living in the camp after I left in later 1945. I have wondered since if they were permitted to stay in Australia remembering that the White Australia Policy was still operating at the time.

The first indication to me of impending trouble was arriving at work and seeing a leaflet which had been placed on the desk of a Javanese called Sarbini, who worked with us in the Map room. Before Anyone could read it Hendrik had torn it up. Soon after that the strike occurred which seriously disrupted the running of the camp. It was feared that there might be physical attacks, especially on women but we Australians walked freely at all times knowing that the Unions were supporting the Indonesians. “Mandrake” and his fellow workers, walked idly round the camp and because they were on strike, were refused access to the canteen. I was in sympathy with them but did not know how to help.

From that time on the Dutch were desperately trying to get their army back into Indonesia, thwarted by their ships held up in Brisbane and Sydney by the striking crews. The film “Indonesia Calling” gave a good account of the events of that time. A few planes managed to lift some of the people but not nearly enough.

It was decided to load and man the vessel Van Heutsz with Dutch naval personnel. The wharf was closed off, supplies were made available through war time regulations thus avoiding the Union ban. Everybody had to work. With friends I stood on the banks of the Brisbane river and waived goodbye as the Van Heutsz steamed away without the aid of tugs and to the applause of other crafts sounding their sirens. A newspaper cutting of the time gave the ships destination as Sumatra but I have always believed it was to Java. Many of my friends were on board, including my future husband and it was not long before some came back and settled in Australia.

There is another story of an Indonesian who was in Melbourne in 1942 with his wife and child. I shall try to find out more of this, but it is difficult to find members of the CPA who were active at the time. The CPA member who asked my friend to hide him is now dead. It seems he was broadcasting anti Dutch propaganda into Indonesia and Australian police were trying to find him. I am puzzled as to how he came to be here. My friend gave him shelter for a week of so but has no knowledge of what happened after that. All that he can remember is that the wife was very frightened.

Now events have gone full circle. The oppressed have become the oppressors. The Australians who supported the Indonesian independence are now opposing the take over of East Timor and Irian Jaya – a familiar pattern down the ages.

I don’t want any acknowledgement in your thesis, but I would like to have the photos back. The writing on the back was done at the time

Jean van Schilfgaarde

Below: Indonesian night in Brisbane that Jane mentioned, raised $300 for the NEI and Australian Red Cross. The evening was supported by Australian ladies from Camp Columbia. Collection Jean van Schiffgaarde Jack Ford.

An additional letter from Jean to Jack (15-6-1992) includes the following information.

Unfortunately, I cannot tell you much about Commander Salm and Colonel Spoor.

The former I saw only a few times in Melbourne and my memory of him is a portly man, not very tall, in naval uniform with lots of gold braid. I did not see him in Brisbane, but I think he might have been involved in the sailing of the Van Heutsz.

Colonel Spoor I remember as a tall good-looking man in army uniform who lived in the married quarters in the camp with a woman known as Mrs Earlis (phonetic spelling as I did not see the name written). They were a bit aloof from the rest of the inhabitants and I saw them walking on Sundays through the surrounding bush land. My late husband had great respect for him and told me he was a very talented man.

There are Dutch people in Melbourne who could tell us much more, but I hesitate to approach them as it is such a long time since I have seen them.

See also:

Joan McConachy – secretary at the Dutch Army at Camp Columbia