The following article was written by Douglas Hurst and includes the information he received from Joan van-Embden-Butler (nee Butler) one of the Women Army Corps (WAC) who also stayed at Camp Columbia in Brisbane.

The Women Corps

Our lives are often shaped by events beyond our control, and so it was for Ineke Thysse during WWII. Had the Germans not invaded Holland in 1940, she would have studied architecture there instead of Sydney. And if the Japanese had not invaded the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia) in 1942 she would have finished her degree. Instead, Ineke became a medic in the VK (Vrouwen Korps) – the Women Corps of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (the KNIL).

The VK was authorised by the Dutch Government-in-exile in London and founded on 5 March 1944 in Australia. Throughout the world, Dutch women (by birth or marriage) were notified and responses came from far and wide. Ineke recalls: ‘Netherlands West Indies women, followed by women from the USA, Canada, and even South Africa.’ She also: ‘knew a woman who had escaped the Netherlands, still occupied by Germany. She arrived in England as a so called “Engeland Vaarder”. From there she travelled to Australia to join up in Melbourne.’[1]

Ineke had been studying in Australia for two and a half years when the VK was founded. Born and raised in Bandung in the Java hills, she had travelled to Australia on a KPM ship, arriving in Sydney in September 1941. At first, she stayed at Hopewood House, a finishing school at Darling Point, Sydney, along with two school friends, Julie Vreeburg and Nanny Weiffenbach. There, with good friends and pleasant surrounds her: ‘first few months were happy ones and the new environs, customs and the Australians themselves, exciting to me’.[2]

Unfortunately, this idyll did not last, for by March 1942 things had changed greatly. The Japanese now occupied virtually all the East Indies, cutting Ineke of from her family (who she later learned were interned) and from her funding. The Dutch Consul provided a monthly loan – only half the amount her father had been sending – to be paid back after the war. On this reduced budget, she stayed with a Dutch family for two months and then boarded at the University Women’s College until mid-1944.

A reduced budget is better than none, especially when you consider that the Dutch Consul got no money from either Holland or the East Indies, as both were in enemy hands. Nevertheless, good pre-war planning allowed the Dutch in Australia to provide student loans and pay armed forces wages and operating costs throughout the war. Australia gave a grant to help Dutch forces relocated from Indonesia settle in, and provided training, military facilities and supplementary manning for the air corps. Otherwise, the Dutch largely paid their own way.

This was no mean feat. By April 1942 Dutch forces relocated to Australia included the cruiser, Tromp; a minesweeper; three submarines and some hundreds of aviation personnel from the Army Air Corps and the Naval Fleet Air Arm. (Only a handful of army ground forces had relocated as almost all the 121 000 strong KNIL had been killed or captured by the Japanese).

As a result, Dutch military strength in Australia was some two thousand by mid 1942. With time, three more warships, three extra submarines, escapees from Holland and the East Indies, several hundred graduates from flying training in the USA, and Dutch volunteers from around the world arrived, adding another two thousand or more by 1944. Numbers increased still further in mid 1945 following the liberation of Holland from German occupation.

During the war the Dutch also bought and paid for hundreds of aircraft and additional ships. The money came from two main sources – private Dutch wealth in neutral and allied countries (which was appropriated and paid back post-war), and Dutch Government funds pre-positioned in places like the USA, England and Australia.

In some cases, large sums were involved. In a US magazine article of late 1941, Major General Van Oyen – then head of the East Indies Aviation Corps and later head of Dutch forces in Australia – stated that his government had US$500 million to spend on American aircraft. As he could then buy seven B25 Mitchell bombers for a million dollars, this sum alone helps explain what seemed a Dutch financial miracle to most people – including many Dutch servicemen who had no idea where the money to buy equipment and to pay them came from.

So it was that some canny Dutch management not only paid for their armed forces in Australia but kept people like Ineke Thysse solvent as well. Study took up much of her time, but as she later wrote: ‘I wanted to contribute to Australia, the hospitable country in wartime, and worked as a volunteer (in Airforce House) …the Land Army as a cherry picker (Nashdale)…(and) as a draughtsman at CSIRO drawing-office on the university grounds.’[3]

The formation of the VK provided an opportunity to do more, but only if she eventually sacrificed her studies to serve. Nevertheless: ‘Although the choice was very hard for me, I joined the corps in Sydney immediately.’[4]

As one of seven initial trainees (her registration number was 4/VK) she soon began military training, doing marching on the roof of the Kembla building and driving instruction at Liverpool with Australian instructors. The all-important medical course was lectured mostly by Doctor van Leent from the Sydney base of the KPM shipping line.

Van Leent was one of many unsung heroes who did significant extra work to help the war effort in those times. Liewe Pronk, the war-time manager of the KPM Sydney base, described him as:’ not only a damn good doctor, but a brilliant organiser as well.’[5] One example of his lateral thinking and organising skills was the building of the Princess Juliana hospital in Turramurra to cater for KPM personnel based in Sydney throughout the war.

In this case, he ran the VK medical course in addition to his normal duties as doctor to some 1 800 Sydney-based KPM personnel. And, from Ineke’s description, he cut no corners in doing so. The training was very thorough, consisting of lectures on anatomy and physiology, injections, laboratory work, and practical work ‘in a Dutch clinic, hospital and sanatorium’, where ‘patients were mostly (native) personnel from KPM ships’.

Then, ‘about ten months after joining we – the first group – were sent up north to New Guinea (to Hollandia, now Jayapura) and further on. The idea was by ‘island hopping’ to reach reconquered islands of the Indies and care for the sick native people…. A second group of women were also medically trained by the KPM doctor in Sydney. In Melbourne women started in the administration course. Some…went to Brisbane later on. Women from Perth also went to Camp Columbia in Brisbane.’ [6]

One Perth women who worked in Camp Columbia was Joan van-Embden-Butler (nee Butler). Recruited in Perth by visiting Dutch officers, she and two others – Ms. Dina Freese and Mevrouw Johanna Mol – travelled first to Melbourne on a train journey ‘which seemed to never end across the Nullarbor’. There they were measured for uniforms and sent on to Brisbane, second class, arriving on 15 August 1944.

Camp Columbia, at Wacol, was the site of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) government-in-exile in Australia – the only such government ever based in Australia. Formed in April 1944 by royal decree and with exceptional temporary powers lasting until the restoration of Dutch rule in the NEI, it had seven departments: defence; NICA (Netherlands East Indies Civil Administration), a bureau to re-establish civilian rule in the restored NEI; economic affairs; education; home affairs; finance; and public works.

NICA was originally established in Melbourne, where all Dutch government and military forces were first administered on arrival in Australia. However, in 1944 Dutch civil administration, and most of the army’s ground force that had now grown to some hundreds, was relocated to Wacol.

At Wacol, Joan Butler found that ‘although army life didn’t disagree with me, I had plenty to learn. In camp Columbia there was Soldatenschool (Army School), Maleise Les (Malay lessons), and last, but not least, Nederlands Dutch. My parents, having come from Zeeland only spoke their Zeeuwse dialect, as did I.’

As VK 43, after a few months she was promoted to Corporal. Army life was ‘definitely different from my life before on my parent’s farm. Then I was a Land Girl, doing my part for the men at the front. I milked cows, picked fruit, managed a team of eight horses out in the paddocks and rounded up sheep with our Border Collie dog…plus many other chores.’[7]

Today we would call Joan ‘multi-skilled’ and she continued to be so at Wacol, working at the switchboard, in the motor pool as a driver, and at a range of clerical tasks, mostly in the Supply Depot. In all, her life was complete contrast to the family farm. ‘Meals were in huge mess halls. We were given P.T. (physical training) by ex-boxer Bep van Klaveren’…and… ‘there were open air movies, at night, when we didn’t have lessons of some kind. Our uniforms were very smart, I thought, Olive Drab. For summer we wore Khaki.

When we were free, we went to Surfer’s Paradise, or were sometimes taken by an officer with a car to dine at Lennon’s Hotel in Brisbane (General MacArthur’s headquarters, with guards at the door- ed his office was in what is now the MacArthur building, not in the hotel). There was a shuttle bus to and from Camp Columbia to the town hall, Brisbane.’ One popular spot was the ‘Dutch Club’. ‘Here you would meet military and civilian people of all sorts – flyers, sailors, officers, NCOs, soldiers, NICA people – in general, all kinds of people having something to do with the war effort.

Romance was in the air with so many young men and women…one dashing Lieutenant stood out – he meant business. He asked me to marry him, we became engaged on 15 March 1945, and married on 2 August 1945.’[8]

Joan’s husband, Otto van Embden, was typical of many Dutch servicemen in Australia who had gathered from around the world to fight the militarist Japanese. A B25 Mitchell bomber navigator- bombardier, he had escaped from Holland just before the German occupation, trained in America at the Dutch flying school at Jackson, Mississippi, and finished up in Australia, flying operations mostly from Batchelor airfield, just south of Darwin.

A wireless air gunner friend, Hans van Beuge, wrote of him that ‘Otto was a Dutch Jew. His father had been a prominent figure in the Netherlands – a professor of one thing or another and a member of the Dutch Parliament. The family lived in a stately home at one of the best addresses in Amsterdam and were just one step ahead of the invading Huns when they escaped to England’.[9]‘

Such is war. A young woman from Western Australia and a young man from Amsterdam meet and marry in Brisbane, a place neither may ever have gone to in peaceful times.

Ineke too met her husband because of the war – he was a Dutch civilian working with NICA – and also married in Brisbane, but otherwise her wartime experiences are generally quite different from Joan’s. As a medic, Ineke worked mainly with small medical teams in hospitals and clinics, not in large camps like Camp Columbia, and so meet few other VK members in those times.

She did, however, travel to many and varied locations dispensing medical care and administering POWs. Following two weeks in her initial posting in Hollandia, she was sent, along with a doctor and two nurses, to Moratai (an important allied island base to New Guinea’s northwest) to work in the hospital. They were later joined by VK members from Surinam and Curacao, and ‘we cared for many ill locals, worked in the laboratory and gave injections for all sorts of illnesses. We even went around the island in a PT boat to visit coastal sick people. We learned a lot from the Indonesian nurses (men) who were also in the small hospital.’[10]

The Pacific War over in August 1945, Ineke returned to Australia to join a small team sent to at first to Singapore to register Dutch POWs in hospitals and within the safety of camps. They also did this work in Palembang and Lubuklinggua in Sumatra. Names and addresses of ex-prisoners were sent to Batavia where a Displaced Persons Register of the hundreds of thousands of people made POWs or otherwise displaced during the war was being compiled.

Along with two VK members from Canada, she then worked handing out clothing material to ex-POW women and generally helping with things like mail deliveries. This again took her to Palembang where ‘we had to be protected by Japanese, Ghurka and Sikh troops against Indonesian extremists’.[11] Sadly, the humanitarian nature of their work gave them no protection and force of arms was essential. Faced with anti-colonial extremists targeting Dutch and Chinese people, British forces in Indonesia to take the surrender brought in Ghurkas and Sikhs and rearmed some Japanese troops. These measures saved many lives, but many Dutch and Chinese still were killed in these times.

In December 1945 Ineke was allowed to travel to Bandung to visit relatives released from prison camps, but did not see her eldest brother, who had been a POW in Japan, until months later in Batavia. Meanwhile, her husband was working with NICA on Banka Island. She eventually joined him there and worked in the local hospital until her demobilisation on 31 December 1946.

Joan Butler travelled less than Ineke, but through her time in Camp Columbia met more people. Some were civilians – her lifelong friend Jean Ayling, a civilian co-worker, among them. Most were military, however, and quite a few were from the VK, the source of which changed a good deal with time. The early VK was drawn from women already living in Australia – VK 22, Mia La Bree, a student at Presbyterian Ladies College in Perth, was a typical example. Others had left the Indies for Australia before the Japanese invasion – VK 47, Hazel Whitton, Ms. Dina Freese and Mevrouw Johanna Mol among them.

Some ‘Engeland Vaarders’ who had escaped occupied from occupied Netherlands to England, also arrived in the early days. One, Lieutenant Yvett Bartlema, was decorated on the way through by Queen Wilhelmina (then in exile in England). Another, Helen Sisage, had played a role in the British movie, ‘One Of Our Aircraft Is Missing’, about a bomber crew who were shot down and sheltered by Dutch farmers.

Joan also recalls that: ‘Some VKs were in Camp Columbia for only a short time before being posted elsewhere; some as nurses, some as parachute packers in Dutch controlled New Guinea’[12] Still more passed through after the southern part of the Netherlands was freed in October 1944 and women from the Netherlands joined up and subsequently came to Australia.

Recruitment did not end when the Pacific War ended. Many women joined the VK for service back in the NEI to help with POWs and other abused or needy people. Some freed from internment in Japanese prison camps joined to be trained and return to help restore health care and other civil services.

On 18 September 1945 the VK Commanding Officer, Captain Janet M.Meerburg, issued a movement order transferring all VKs at Camp Columbia to the NEI. Many served there until the Republic of Indonesia was declared on 27 December 1949.

In all, 1019 women served in the VK over a period of almost six and a half years. The NEI army, the KNIL, closed on 26 July 1950, and with it the VK. In recent years reunions have been held in the Netherlands and Joan and Ineke, who had never met despite both being part of the VK’s early days, have finally become acquainted.

In concluding her notes on the VK, Joan wrote that: ‘I gained no medals, but I consider I did my duty doing what I could.’ Much the same could be said for the VK as a whole. Little known and almost forgotten, it served its country loyally and professionally in critical times, and in doing so became a part of the shared history of Australia and the Netherlands.

[1] Notes provided by Ineke Thysse, 18 June 2004.

[2] My Australian Memories, an article by Ineke Thysse dated May 1989, an unattributed copy of which supplied by Hans van Burge.

[3] My Australian Memories, by Ineke Thysse (as above)

[4] Ibid

[5] KPM 1888-1967 – A Most remarkable Shipping Company, by Lieuwe Pronk, a private publication

[6] Notes provided by Ineke Thysse, 18 June 2004.

[7] Notes provided by Joan van Embden-Butler, 14 May 2004.

[8] Ibid

[9] Notes provided by Hans van Beuge, 24 February 2004.

[10] Notes provided by Ineke Thysse, 18 June 2004.

[11] Ibid

[12] Notes provided by Joan van Embden-Butler, 14 May 2004.[12] Notes provided by Joan van Embden-Butler, 14 may 2004.

See also: In exile but not passive: the Dutch women’s Vrouwenkorps in Fremantle

Multi-skilled WAC Joan Butler

These are the original notes provided by Joan as she wrote them down for Nonja Peters in 2022

A friend of mine, living in Perth, Dina Freese, who was a few years older than I, had read in the local newspaper that Dutch officials would be coming to Perth to explain the details of the Dutch Women’s Auxiliary Corps (V.K.).

On 17th May 1944, two gentlemen arrived in Perth: Lt. Col. de Stoppelaar (for the Army) and Lt. Commander de Groot (for the Navy). They came to address the Dutch women at the Palace Hotel, Perth, with arrangements made by the Consulate of the Netherlands.

In a letter from Lt. Col. de Stoppelaar, Temple Court, 422 Collins Street, Melbourne, dated 13th June 1944, I received forms and a medical report to be filled in by myself and a medical doctor.

My Movement Order, dated 20th July 1944, directed me to travel to Camp Columbia, Brisbane with Mej. Dina Freese and Mevrouw Johanna Mol, to arrive there by 15th August 1944. We traveled by train across the Nullarbor, a journey that seemed endless. In Melbourne, we were fitted for uniforms, including the cap, marking the beginning of our military life. We reported to Camp Commandant NEI Army H.Q., Sub. Lt. Bieger, from whom we received 2nd Class Tickets to continue our journey to Brisbane.

Before I left W.A., I had received a letter from the Camp Commandant at Camp Columbia, Lt. Col. de Stoppelaar, stating that we would be met at the Brisbane station on 15th August and wishing us a good trip, “een goede reis.”

Upon meeting him at the Camp Commandant’s Office, I’ll never forget the welcome. His first words were: he’d never seen such healthy girls! I took this personally to heart, being the youngest of our group. I presumed the healthy farm life must have shown! A mention of our departure from W.A. had appeared in The West Australian and Daily News.

Although Army life didn’t disagree with me, I had plenty to learn. In Camp Columbia, there was Soldatenschool (Army School), Maleise Les (Malay lessons), and Nederlands (Dutch). My parents, having come from Zeeland, only spoke their Zeeuwse dialect, as did I. Initially, I had my own room in the “C” Area (women’s area), closed off from the rest of the camp with barbed wire. My neighbor was none other than Mevrouw Spoor, the wife of the General. Later, I moved to the Barracks, sharing a room with a mate (“slapie”).

We had to learn a lot: marching in single and double files (exerceren op een gelid), standing to attention (de houding), forming ranks (het aantreden), “geeft ACHT” (Atten-TION!), standing at ease (het op de plaats rusten), numbering off (het nummeren), at ease (het rusten), breaking ranks (het inrukken), forward march (voorwaarts-MARSCH), etc. Learning the ranks (Rangen) was essential, and all orders were given in Dutch, which some of us were still learning!

After a few months, I was promoted to Corporal (Korporaal). I was V.K. 43.

Army life was definitely different from my previous life on my parents’ farm. As a Land Girl, I milked cows, picked fruit, managed a team of 8 horses, rounded up sheep with our intelligent Border Collie, and handled many other chores. I even followed a dressmaking course by correspondence, which wasn’t easy without a telephone to ask questions.

At Camp Columbia, I first operated a switchboard, then moved to the Motor Pool where we learned to drive with American WACS. By then, other women from the West Indies had arrived. The first Australian group had already done some training in Melbourne and were established in offices. I eventually worked in the Supply Department opposite Lt. Col. de Stoppelaar’s office, keeping records on equipment and clothing.

Our meals were in huge mess halls. We received physical training from ex-boxer Bep van Klaveren, who also ran the PX Store. We had open-air movies at night when we didn’t have lessons. Our uniforms were smart, olive drab for winter and khaki for summer.

We were once invited to an American Women’s Army Camp to showcase our marching skills. The C.O. was impressed, given our short training period.

During free time, we visited Surfer’s Paradise, dined at Lennon’s Hotel in Brisbane, and took a shuttle bus to the Town Hall. We often went shopping and attended the well-known Methodist Church frequented by Americans. We also visited the “Dutch Club,” meeting various military and civilian personnel involved in the war effort. Sometimes, civilians invited us to their homes, leading to lifelong friendships. My good friend Jean Ayling was a civilian co-worker at the Supply Department, and we maintained our friendship for over 42 years.

Romance was in the air with many young men and women around. One dashing Lieutenant stood out, proposing to me. We became engaged on 15th March 1945 and married on 2nd August 1945. Otto’s parents had escaped from Holland on a fishing boat during Hitler’s invasion, leaving behind their possessions. They spent the war in humble accommodations in Cambridge, England. Otto passed away on 7th March 1981 after 36 years of marriage.

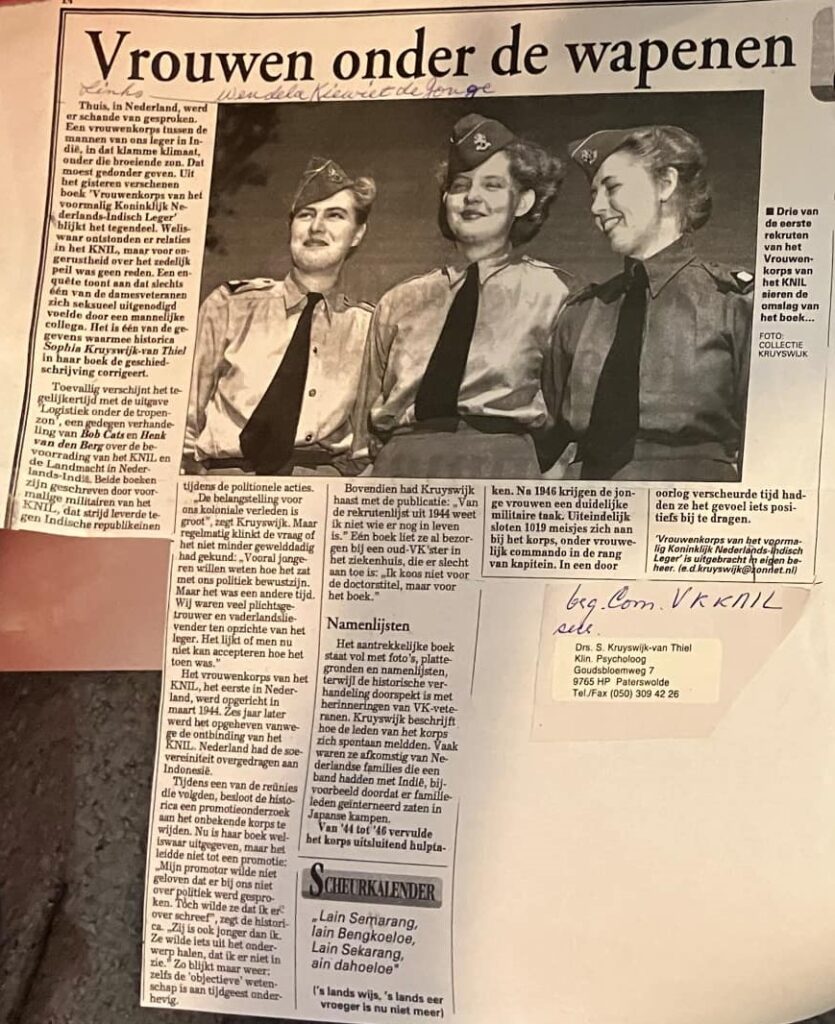

Recently, I attended the graduation ceremony of Dr. Sophia Kruyswijk, who wrote a dissertation on “Vrouwenkorps Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger 1943-1950.” However, her history mainly covered post-war recruits from Holland, with little mention of Camp Columbia except some photos from my barracks mate, Wendela Kiewiet de Jonge.

A large group of VK’s from Australia was left out of her book. The first VK women were already living in Australia, some studying at colleges, like Mia La Bree, V.K. 22, at Presbyterian Ladies College, Perth. Others had left the Indies before the Japanese invasion and were living in Australia, like Hazel Whitton, V.K. 47, Mej. Dina Freese, and Mevrouw Johanna Mol. There were also “Engeland Vaarders” who had escaped from occupied Netherlands to England, like Lt. Yvett Bartlema and Helen Sisage, who had played a role in the British movie “One of Our Aircraft is Missing.”

Some VK’s stayed at Camp Columbia briefly before being posted elsewhere, like nurses and parachute packers in Dutch-controlled New Guinea. Later, VK’s arrived from the USA, Canada, Dutch West Indies, and Suriname.

On 18th September 1945, a Movement Order was issued by Captain Janet M. Meerburg to transfer all VK’s at Camp Columbia to the Netherlands Indies. I have an original copy with all the names, ranks, and numbers of the VK’s at that time.

My connection with Wendela Kiewiet de Jonge is twofold: her brothers, Coen and Joost, were pilots with the 18th Squadron, NEI Air Force, and my husband Otto often flew as Navigator/Bombardier in Coen’s crew. Otto was a skilled navigator, ensuring safe returns to base and locating minute islands in the Pacific.

We remember all those who sacrificed their lives for freedom.

I gained no medals but believe I did my duty.

Joan

Ella Bone from Fremantle to Camp Columbia

Ella Bone was living and studying in Western Australia before the Pacific War, part of a small Dutch-connected community that included students from the Netherlands East Indies. Her civilian life was abruptly disrupted in December 1941, when the Japanese entry into the war led to emergency evacuations and sudden uncertainty for Dutch and British nationals in Australia. Ships carrying evacuated children and students returned almost immediately to Fremantle, illustrating how quickly the strategic situation deteriorated. During the war years, Ella moved into Dutch–Allied wartime structures in Australia and later worked in Melbourne in an administrative environment linked to Allied headquarters. In 1944, following the establishment of the VK-KNIL, she enlisted and was posted to Camp Columbia at Wacol for training. Her service reflects the experience of many young women who transitioned from civilian displacement into formal military support roles and connects Western Australia, Melbourne, and Camp Columbia within the broader story of Dutch women’s wartime service in Australia.

WAC story of Sophia Kruyswijk

See also: