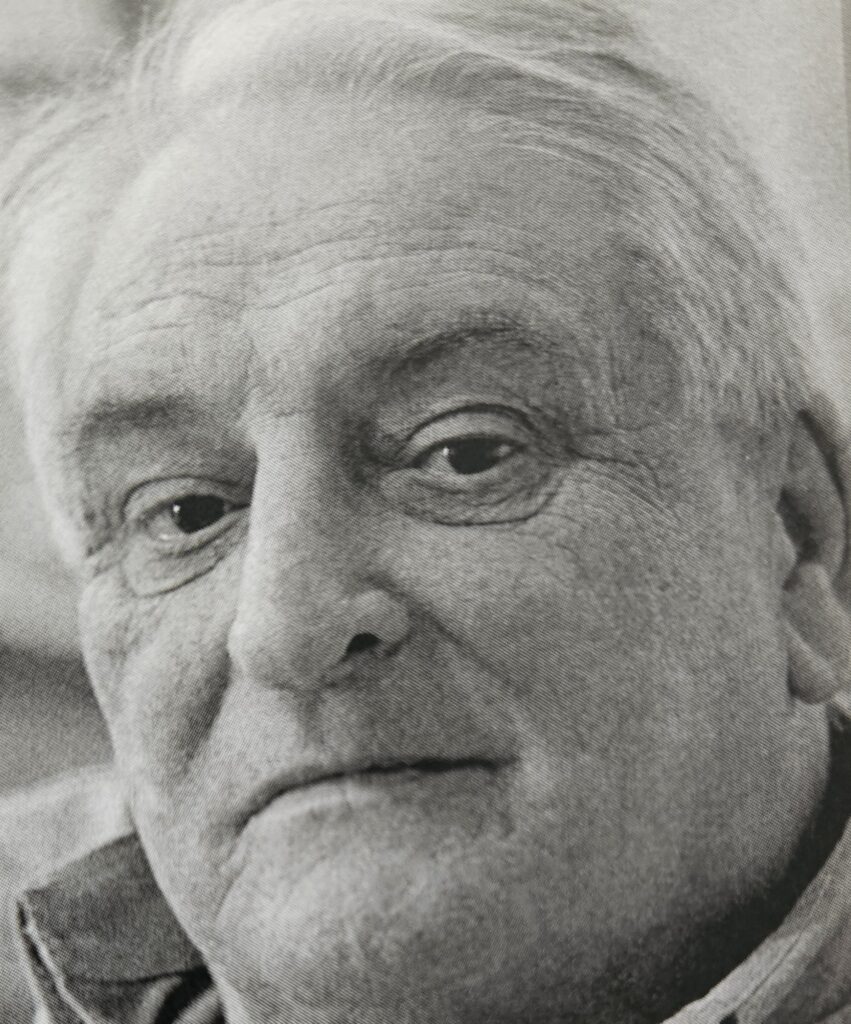

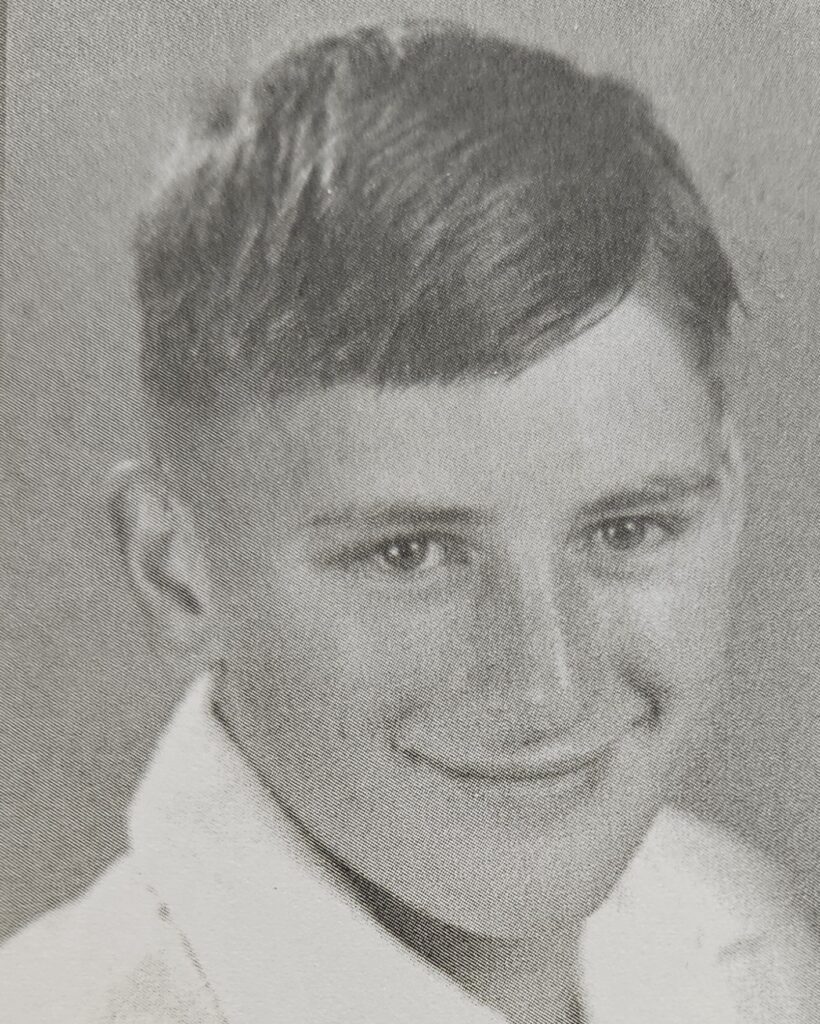

My parents were both immigrants. My mother was English, born in 1897 west of London; she arrived in Australia in 1915. My father was born in 1906 in Switzerland, and he came to Australia in 1929-1930. They met and married here and moved to Richlands in 1931. I was born in 1932, at Lady Bowen Hospital, Brisbane. My half-sister Joan was born in 1918, and my younger brother Marc in 1934. Our family lived in Richlands from 1931-51.

Before the war, there was little employment available. My father did “Relief work” for a Depression program in the late 1930s—about 3 days a fortnight for a married man—on road works at Breakfast Creek, then later at Somerset Dam. For that time, the whole family would walk to Ipswich Road on a Sunday evening, where a ute would come along and pick him up: the men would camp at the dam for the week. He collected the dole at Oxley Police Station.

Mother worked as a cleaner during the 1930s, with clients in Graceville and Chelmer. At home, she was a good manager, so we were unaware of any hardship.

\

Wartime Richlands

I was about 7 when the war started and 13 when it ended. The Richlands I knew then consisted of only about 20 families, about 7 of them Italian. It was an isolated place consisting of mainly 2 groups—Aussie battlers worn down by the Depression, and hardworking immigrants determinedly building a new life.

We had no car, but I remember many motor cars at that time had gas producers attached. This ugly contraption generated gas from charcoal. Travel was particularly restricted during the war—so we were quite an insular community.

Entertainment was an occasional picture show at Sherwood. Little amusement was expected: we simply lived our lives, and we were never bored.

Richlands State School 1938-46

There were only 30-40 students and one teacher when I started school in 1938, and just three or four at my level. No one wore shoes to school—they were only to go to town, and I hated wearing them. We always had cuts and sores on our feet: forcing them into shoes to go to town was no fun! Our feet hardened so that even on a frosty winter’s morning we didn’t suffer.

Pino Zerlotti (who had left school) would come and play the violin for our singing activities. I remember “Drink to Me Only,” “Last Rose of Summer,” and “Marching Thru Georgia.” Maybe they were the teacher’s favourites; they made no sense to me!

In the grounds, we played Cowboys and Indians, marbles, and cricket and soccer—though it was often hard to find two teams. On Sundays, Mrs. Sparrow ran a small Sunday School under the school building for the Anglicans. Only a few kids attended.

From 1942, we had air-raid trenches in the school grounds; I think the parents dug them. I remember the older boys working in them, but perhaps they were just bailing out the water after rain.

We had to have regular drills. The teacher would blow his whistle, and pupils would come racing from all over the four-acre grounds into the trenches.

One day, a few of us obtained a similar whistle and blew it. It had the desired effect—kids came running. But so did the teacher—and were we in trouble!

Windows were taped to prevent flying glass in the event of a bomb blast. The threat of Japanese invasion was real.

The Borgeaud Home

We lived on eight acres at the corner of Pine and Orchard Roads. My father built our house, with help from neighbors; this reciprocal help was normal in the community.

The house was made of fibro sheets, unlined and unpainted, with a tin roof and a veranda on the front. Our light at first was from kerosene lamps—we pumped the kero from a square four-gallon drum with a pump—and our only heating was from the kitchen stove. I remember the day the electricity was to be put on in 1940-41: I could hardly wait to get home from school to switch on the electric lights. We all helped to chop wood for our stove—and unlike some, my father cleared just the undergrowth on our land, so we always had trees for wood.

There were no council services. The roads were unmade. There was no sewerage service; we used an earth closet and buried our own. There was no rubbish collection—which was no problem because what little waste we created, we buried.

We were on tank water—with a tap through to the kitchen. If you turned the tap on carelessly after a storm, the pressure would spurt water with considerable force across the room! Some people lined their tanks with concrete to prevent rust; this provided beautifully cool water in the hot summers. We also had a well to water the gardens, with a pump to raise the water.

Like everyone, we had a vegetable garden, chooks, and a cow, and so were largely self-sufficient. We had no fridge or ice chest, just a meat safe. All our food was freshly prepared, bought that day or picked from our garden—and all was cooked at home. Our standard evening meal was meat and three vegetables, and always a pudding—sago or tapioca or stewed fruit, maybe junket.

My father put about two acres under cultivation, growing lettuce, tomatoes, etc. The produce was taken to market by Timo Zerlotti and Bill Beauclerc, who carted for the district in two of the few local trucks. Most people had a horse to plough their land—there were no tractors in Richlands!

Darra and Richlands

For us, Darra was the centre for shopping, services, and social activity—at the Darra Hall. There were shortages, and from 1943 we needed coupons for some food, e.g., meat, sugar, and for clothing. We boys would ride our bikes to Darra to the closest butcher and baker for our mother. We were always on tenterhooks in case we didn’t have enough coupons. I particularly recall one trader who became a “Little Hitler” during the war.

At first, we had our hair cut by a Russian barber at Darra; it was a luxury to have him put scented water on our hair after our “short back and sides.” Later, we had to go to Corinda. Our doctor and pharmacy were at Oxley—Dr. Angus Buchanan (Snr) and Mr. Hal Houghton.

The War

In 1942, my father built an air-raid shelter in the wall of the creek about eighty yards from the house. There were no air-raids, but it was a great place to play by candlelight.

My father was beyond the call-up age (and he was not a British subject at that stage). There were a number of WWI veterans in the area, e.g., Gillespie and Connell, and most others were farmers, so very few locals enlisted.

In the hysteria of early 1942, some people were quick to label the local Italians as enemies (and some Australians were simply jealous of those immigrants who had made good). In fact, a number of local Italians were passionately anti-Fascist, and the rest were just thrilled to have some land in Australia, so it was unfair that the term “Dago” was thrown about after Italy joined the war. My father forbade the use of the word in our house. He had an accent too, and had felt isolated, so he had an affinity with the Italians and liked to visit them for a chat.

Communication

Everyone followed the news closely on their battery/valve radios. (There were official ABC war news bulletins at 7:45 am, 12:30, and 7 pm, which all stations broadcast). I remember on December 7, 1941, I heard of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on the news at 7:30 am. On the way to school, I saw Alfie Gavioli working on his father’s farm, and I told him the news. I was nine.

We listened to the news both morning and night. I remember my (English) mother was very upset when she heard that Coventry had been bombed by 500 German planes, and Coventry Cathedral destroyed. But when I told the boys, one said he “couldn’t care less.” The plight of the Australian Rats of Tobruk got more attention.

The daily newspapers were read from front to back. All the families picked up their “Telegraph” from Mr. Jim Gudge’s, who brought them by bicycle from Darra. (Or maybe it was from Johnson’s Garage on Ipswich Road, where they were tossed off the Telegraph truck on its way to Ipswich).

The nearest phone was at Frank Johnson’s garage on Ipswich Road. My father had to run there to call the ambulance when the births of my brother and me were imminent. I remember my father telling us he heard our old Boer War veteran Jim Gudge, ringing Chandlers about his radio—”I don’t know what’s wrong with my wireless! It won’t sing, and it won’t talk.”

The Americans

It was a wet day, probably January or February 1942, when the Americans arrived. My father was home, and we were sitting on the veranda when we heard a low roar. The rumble continued all day, and when I went to pick up the evening paper, I saw Archerfield Road totally churned up, and the troops setting up camp across the road. And I saw them most days from then, marching about their camp. I was curious but never ventured closer; there was a guard hut on Archerfield Road (now at the corner of Azalea Street).

The Americans cut a road right through the bush to Wacol station. That was when I saw my first bulldozer. It was huge! We didn’t realise they could turn on a sixpence, and when it turned towards me, I really got a fright. Their huge equipment was always fascinating to us.

All through the war, there were, of course, jokes about the troops, but no animosity towards the coloured soldiers by the local people, who were battlers too. I never saw a coloured soldier with a gun, but the officers and MPs, who were all white, always wore them.

The MPs were rather racist. There were shootings at Darra. A local resident tells a story of a black soldier knocking on their door, terrified. The family hid him and lied to the MPs when they came searching for him. We heard other disturbing stories too.

A few local families invited soldiers home; we kept to ourselves. We did go to the open-air pictures at the camp a couple of times. I remember “Green Hell” (about the jungle) and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” These were exceptional experiences for us.

Fraternisation

I remember hearing some local girls—about twenty years old—giggling excitedly about their trip to Brisbane wharves to see the American ships—and the servicemen, who were a hit with the local girls.

The American soldiers were nicely dressed and had more money—plus gifts for the local girls. The Australians couldn’t compete, and there was a lot of resentment.

Of course, there were some “camp followers.” A group of women came into Richlands and rented a house in Pine Road, quite near the camp. There always seemed to be some soldiers hanging about there. And there were a few local black babies. A couple may have been adopted out because the mothers were so young, but others grew up in the community, e.g., one went to school with my sister-in-law.