Pino in 1939

I was fourteen when war was declared. I was attending Central Tech three days a week, studying architecture. I would ride my bike the three miles (5 km) from Richlands to Darra, put it under the Station Master’s house, take the train to Brisbane, then walk to the Tech (now QUT). Even on those days, I was needed to help my father on the farm—it was my job to milk the cow and feed the fowls before I left. When I turned eighteen (in 1943), I was called up but exempted because of farm work.

I was called up a second time in 1945—but the war ended the next day!

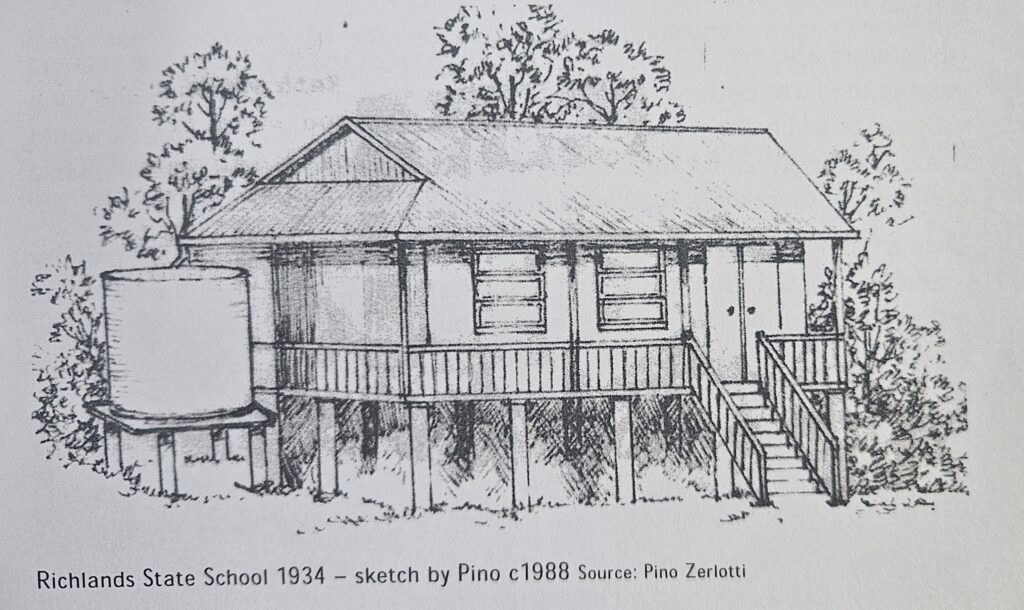

Richlands in 1939

The Richlands area was then considered an outpost of Darra. There were probably only 30 plus families in the immediate area—about 10 Italian families, the rest mostly Australian. Families (especially the Italian men) would often get together at night at one family home for a game of cards and a chat. There were two houses at the end of Archerfield Road made of bush timbers, with walls of corn sacks covered with a slurry of cement. Our first house had been similar. Richlands School (opened in 1934) had one teacher and about 60 students. The elder students often tutored younger ones out on the veranda. I had completed Year 7 in 1938. The area was all dirt roads—and there were very few vehicles. Most people cycled or walked to and from Darra (3 miles/5 km each way) along Archerfield Road. We had to go to Darra or Oxley for everything—shopping, churches, doctors. Richlands mail was delivered by Mr. Gudge. He couldn’t read, so Oxley PO would sort, and he would deliver to those in Archerfield Rd, then leave the rest on his veranda for locals to pick up.

The Zerlotti Home in 1939

My father had worked hard, even through the Depression, to buy us land. We had now worked our 16.5 acres at Richlands for seven years, my parents were on the school committee, and we felt at home at last. We had just moved into our new house on the corner of Orchard and Progress Roads. This had been built over three years, in between planting and harvesting, by my father Timo, my uncle Vito, and me, with the help of local carpenter and neighbor Len Sharman. It was made of broken bricks—bought from Rylance Brickworks in Dinmore for £1 per thousand—then rendered with concrete. Like all the locals, we had a house cow, chooks, ducks, a veggie garden, and fruit trees: Mum made our own butter and ricotta. While later there was rationing of some things (like tea and sugar), we lived quite well on these “rich lands.” My father had ten acres of land under cultivation, growing pineapples, grapes, melons, tomatoes, beans, peas, etc., commercially. I was always expected to help on the weekends, and Dad had employed Jim Sparrow full-time. Uncle Vito (Mum’s brother) joined us. Our water came from tanks and two bores.

Italy Entered the War on 10 June 1940

Things changed then for many Italian Australians. Overnight we became the enemy—even in the eyes of some neighbors we had known for years. The police visited all Italian families (then about a third of Richlands families). We were given a curfew—no one was to be out after 6 pm. All guns were confiscated—most families then had one to shoot the hares that loved to nibble the new crops.

We were often taunted with “dago,” etc. I was roughed up each night after Tech school at Darra Station. If there were MPs or other people around, the local lads simply waited up the hill. My father—a naturalised Australian citizen—was accused of having tunnels under our house, dealing in guns with the colored Americans, and flying the German flag at night! The accusations were so ridiculous even the Oxley Police had a laugh when they followed up the complaint. A couple of local men were interned. They seemed to be selected randomly just to keep the Italians under control. Both were single—maybe that was a small consideration by the authorities. They were sent to a concentration camp at Enoggera and later into the Civil Alien Corps. But we all continued to work hard and support our families and friends, as always. We really didn’t care about politics and war.

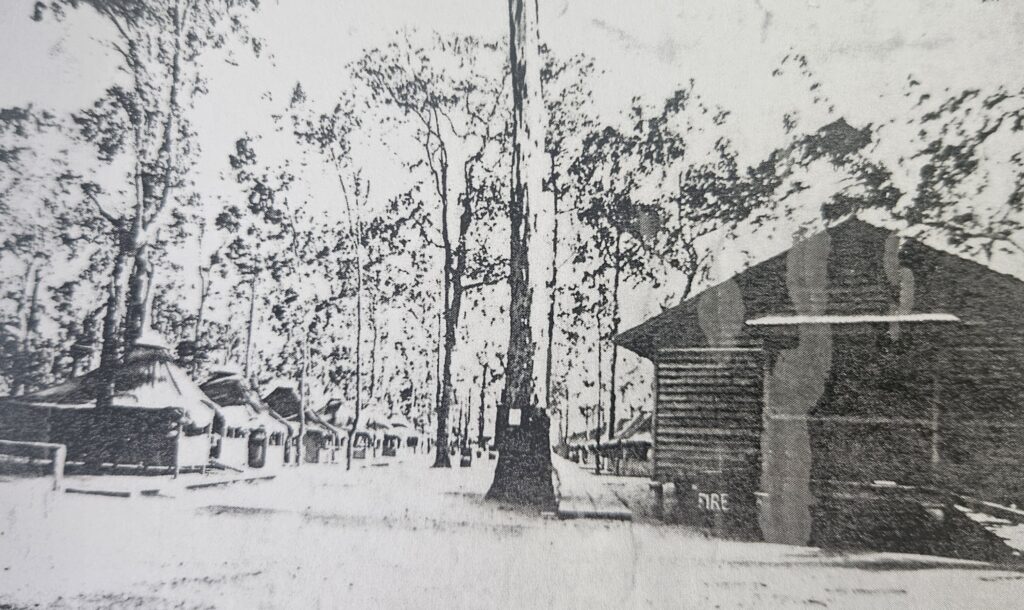

When the US Army Came

It was early 1942 when the first American troops came to Richlands. There was great excitement. Dozens of trucks, tanks, etc., came rumbling through quiet Richlands. They set up camp at the junction of Archerfield and Pine Road (now Azalea St). An area was cleared to make way for tents, and in no time barracks—and an open-air theatre—were erected. Movies were shown every night for the soldiers, and the locals were allowed in gratis. Every day we could see the troops marching around the dirt roads. Their convoys ran day and night, and put up so much dust that, after a few bomb-carrying trucks ran into each other in the murky conditions, the US Army sealed Archerfield Road. Everything was different—so we accepted it all. These were the first Negro men we had seen, but I don’t remember any particular local reaction to the “colored” soldiers. However, we did soon notice that all the officers were white.

Zerlottis Working for the US Army

My father Timo drove his produce to the Municipal Markets in Roma Street twice a week, and I always went to help. He had an International 3-ton truck. Soon after the US arrival, a Negro quartermaster began to buy our whole truckful at the markets and later arranged that his trucks would pick up direct from the farm. The US Army bought a lot of the Zerlotti vegetables throughout the war. My mother also provided support for the Americans. One day, two soldiers passing the farm noticed the chicken pens and asked Mum if she would cook up some fried chicken. From that day, Mum was kept busy: Negro staff would come to order them for the Officers’ Mess—and she would cook them up in a boiler. Soon there were 1000 hens in our fowl pens. Then a young Officers’ Valet came to ask if she would do the officers’ laundry—and she agreed. Soldiers would deliver and pick up clothes for the white officers. My mother was a strong woman, but she later found it was getting too much for her, and called on her friend and neighbor Mena Cantoni to take on some of the workload. So both my parents did ongoing business with the Americans.

Pino and the Ammo Dump

I guess Mum told the soldiers I was studying Commercial Art and working as a sign writer (I was employed by Burns-Philips in Mary St. I was also working two nights a week as a waiter at the Bell Vue Hotel and Bonds Café). What they wanted was for me to write signs for pegs to identify each row of ammo throughout the dump, which was huge, and posters as needed. This was a lot of work, and it continued from 1942 to 1945 when the US forces left Richlands. I worked for them most weekends, but only went to the depot occasionally. Mostly they brought what was needed to the house, and I made up the signs at home. They often brought cigarettes (Chesterfields and Lucky Strikes), which were hard to get. My uncle was the only one who smoked—and he often smoked out the room we shared!

They would sometimes come and get me in a jeep and drive me all over to see the dump. There were miles of tracks, with some ammunition under cover and rows of bombs out in the open. In one area—over near Blunder Road—I saw rows and rows of hundreds of drums of chemicals. One day I saw four graves—two of them open—in the camp, and the officers explained that they were a reminder to the troops “that they could be next.” I was shocked at such stark discipline measures. But the Americans paid well, and I was able to save quite well.

The End of the War

Our family income was greatly increased by the presence of the American camp, and we all worked very hard to make the most of the opportunities of those years. But when they left, we didn’t give it another thought. It was the same when the war ended. Of course, everyone was happy to see the end of war. But I don’t remember any special celebrations in Brisbane or in Richlands. Life went on—work and study, family and community. I was twenty-one when the war ended—and life was good.