I was not quite six when war broke out. I lived with my parents, Ted and Queenie Evans, my older sister Shirley, and (from 1942) my younger sister Kaye, behind the H.L. Jones Beegoods Factory opposite the Goodna Railway Station. In the cottage beside us lived my Grandmother Jones, my aunt Audrey Jones, and Miss Frances Wilde, retired Matron of St. Andrew’s Hospital, Ipswich. Shirley and I attended the Convent School nearby.

One of my earliest war memories is of walking through Grandma’s house on the way home from school and finding her kitchen full of activity. Grandma, my mother, and my aunt Valma Jones were busily soaking strips of calico in a thick mixture of flour and water, then pasting them in a crisscross pattern across the windows. I don’t remember what explanation I was given for this strange behaviour at the time. My father was the district’s Chief Air Raid Warden (perhaps because he was a Gallipoli veteran). After the “blackout” was imposed, it was his duty to make sure other ARP (Air Raid Precautions) members were vigilant. To this end, he would from time to time leave a blind slightly up in our house to see if anyone reported the resultant chink of light.

Breakdown of telephonic communication in the event of an air raid was a serious possibility and various ingenious alternative methods were suggested. I recall my father hanging a large heavy metal ring from our back gate, then striking it like a gong and waiting to hear a response from another Warden on Brickfield Hill. One of the benefits of my father’s ARP role was that he was granted a supply of petrol for his car. Many residents “mothballed” their vehicles for the duration of the war, including our Station Master neighbour, Mr. Blyde. I remember being intrigued by the sight of his car sitting forlornly in the side yard of his house year after year.

After Japan entered the war, householders were advised to create air raid shelters for their families. Ours was somewhat unusual in that it was above ground. My father had used many sandbags to convert our chookhouse into a (hopefully) safe haven. (I wonder where the chooks slept during the war?). In the shelter was stored a small quantity of imperishable foodstuffs, water, reading matter, blankets, etc. At least we didn’t have the problem many others had, of their underground shelters filling with water each time it rained! Included in that category was the shelter dug for the nuns in the Convent grounds.

At school, slit trenches were dug, and we all had to bring small bottles of drinking water in case of an air raid. The Police Station was next to the school, and Sergeant McErlean (whose daughters Clair and Erin were amongst the pupils) made sure there was a large poster on the classroom wall depicting various types of ammunition, with a stern warning never to touch such things if found. Sadly, I recall the day in 1943 when a bomb exploded at the Convent school. One of the boys had found an anti-tank rocket in a paddock at Redbank Plains used by American soldiers from Camp Columbia. He brought it to school and managed to persuade the nun in charge that he’d been told it was a “dud”. She and the boy showed it to the whole school (about 100 of us) so that we would know what a bomb looked like. Mercifully nothing was triggered at that point or the carnage would have been far greater. I was playing in my Grandmother’s backyard when the explosion occurred late that afternoon and the noise of the blast was tremendous, as well as its reverberations. Of the small Scholarship class (which finished school later than the rest of us), one child died and seven others were injured. Such a tragic time for all concerned!

The air raid siren was attached to a pole near the Honour Stone, and we became accustomed to hearing its regular weekly testing using the “all clear” sound. For the two false alarms that we did experience, the sudden urgent wailing of the warning siren was quite electrifying and produced immediate action as the school sprang into air raid drill mode. Because we lived so close, Shirley and I had permission to run home in the event of a warning being sounded. I can remember being absolutely terrified, desperately scrambling through the school’s barbed-wire back fence then a split-rail fence to reach the safety of home.

Another siren memory, but on a much lighter note—many a chuckle was had by those lucky enough to observe the following occurrence. Locals were used to the sight of soldiers on “route-marches” from camps at Wacol, Redbank, or Redbank Plains. On this particular morning, a group of about 40 Negroes was marching briskly along Church Street near the Honour Stone when the weekly siren test began. They had not been warned of its existence, and consequently, as the frightening noise sounded right over their heads, the entire group dived straight into the nearby ditch!

Also near the Honour Stone at one time, there was a large pile of pots and pans etc., as Goodna residents contributed any aluminium they could spare towards the war effort. My mother was intensely patriotic, and she would give my sister and me small amounts of money to take to school on a regular basis to buy War Savings Stamps. These were stuck on a special card provided, and I believe a full card merited a War Savings Certificate. (The www tells me that War Savings Certificates were one way the Government raised additional funds for the war effort. Money was lent to the Government for a specified time period, documented by a certificate, and was payable upon maturation with a modest amount of interest.)

In a small paddock between my Grandmother’s house and the Presbyterian Church, there was an old shed formerly used for storage of honey from my Grandfather’s apiary at Redbank Plains. Ladies from the Goodna Branch of the CWA met there to make camouflage nets on looms, using wooden shuttles carved by my father who, as a lad, had worked in a Yorkshire cotton mill. I recall enjoying the task of taking them morning tea prepared by my mother because they seemed to be such a jolly lot of ladies, happy to be able to contribute to the war effort.

There was a large wooden crate under our house in which my aunt’s piano had been delivered. With the Pacific war coming closer, our few valued possessions—such as my mother’s collection of crystal—were carefully wrapped and placed in the piano case. My father then dug a huge hole and buried it to…keep the contents safe from the effects of bomb blasts. I can remember privately burying one of my favourite toys, a small plaster milkmaid. Sadly, she didn’t survive this premature burial.

Because we had a cow and chooks and a vegetable garden, food rationing didn’t affect us very much except for the meat supply. I do recall yearning for chocolates! Rubber was not obtainable in any form, and at the end of the war, I was delighted to find the toe of my Christmas stocking occupied by a small, red, solid rubber ball.

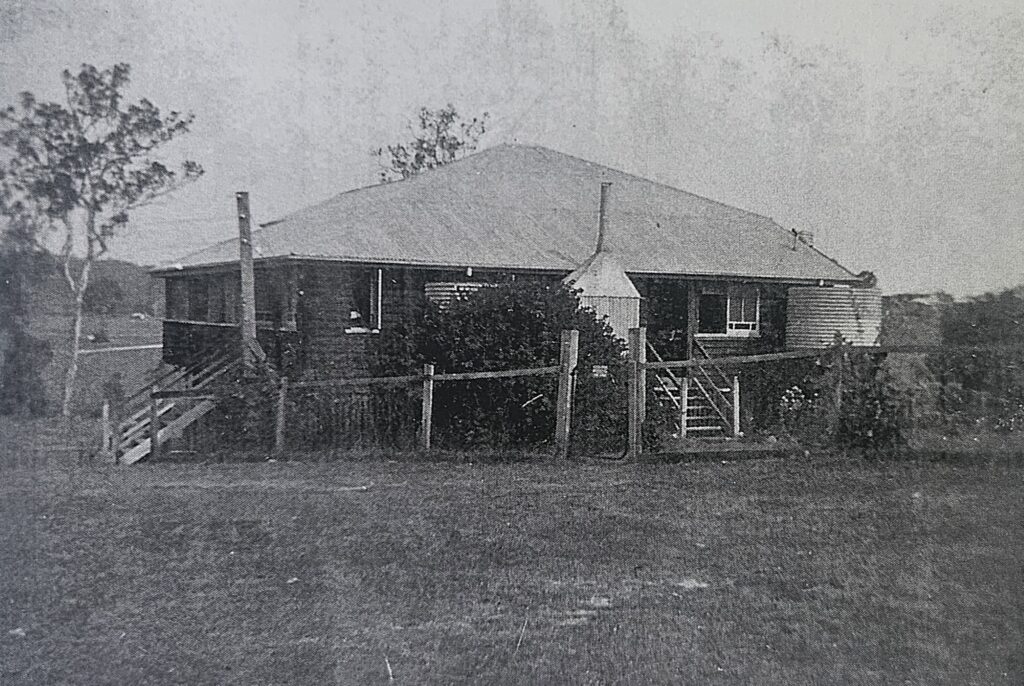

While soldiers from Victoria were camped in the bush at Redbank Plains, many Goodna residents opened their homes to their wives to give the couples the chance of some extra time together before the men left for overseas. A curtained-off bedroom section was created on both front and back verandahs of my grandmother’s cottage for two of these wives.

Shirley and I very much looked forward to the parties held at our home in the early years of the war. Our side verandah would be cleared and planks placed across drums to provide seating. My father would sprinkle something called “Pops” on the wooden floorboards, then my sister and I would take it in turns being dragged around the verandah on a chaff bag to create a polished surface for dancing. Partners for the soldiers were mainly provided by my Aunt Valma, who was nursing at Ipswich Hospital, and my cousin Olive Campbell, who worked for a Brisbane firm. In the lounge room beside the verandah, talented Aunt Audrey (who was blind) would play for hours on her “baby grand” piano, for both dancing and community singing. My dance favourites were “Hands, Knees and Boomps-a-Daisy” and “The Lambeth Walk”. I soon became familiar with songs such as “Pack Up Your Troubles”, “There’s a Track Winding Back” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”.

Games were also popular at these parties, but the only one I can remember is “Haircut, Shampoo or Shave?” This entailed the positioning of three attractive young ladies each behind a chair and offering one of those services. An unsuspecting young man would be called into the room and asked to make his choice. Once seated, he would be blindfolded, and his “attendant” would pretend to begin the service. My father, wearing thick lipstick, would then sneak out from behind her and give the victim a big kiss, after which the blindfold was removed. Great hilarity would ensue as the onlookers witnessed the good-natured discomfiture of the kissed one (except for one man I remember being extremely annoyed) when they realised the identity of the kisser. Suppers on these evenings were magnificent home-cooked repasts, but sadly, my sister and I would have been banished to our beds by the time it appeared. I do remember much finger-licking as we helped our mother in the kitchen earlier in the day.

Living so near the railway line, we would usually see the troop trains from Redbank as the “boys” set off for destinations unknown. On one occasion when some of the men we knew best were due to depart, my mother stationed Shirley and me on what was known as “the flat” in front of our house, just across the road from the station, with an enormous flag to wave between us. There were tanks on that train, and some of “our” lads waved to us as they rode on top of their tank, bare-chested under a beach umbrella!

In the latter years of the war, we got to know some of the Dutch soldiers as they visited our home for meals, music, and relaxation. I have a letter from the family of one in Holland, thanking my Aunt Audrey for the parcel of hand-knitted articles she had made for them. American soldiers also visited our home, and we entertained the crew of the American submarine, the “USS Grampus” for a short time during their stay in Brisbane. After the submarine was lost at sea in 1943, my mother corresponded with some of their families for many years.

Books were very hard to come by during the war, so I was thrilled when our Victorian soldier friends arrived one day with a box full of children’s books. They’d been amongst a quantity of second-hand books sent to the camp by well-wishers. It was a real bonanza for me! One of the books, Mary Grant Bruce’s “A Little Bush Maid,” started me off on a lifelong love of this series. My parents had plans for our evacuation if necessary to the dairy farm at Boonah owned by my uncle and aunt. Because I loved visiting there, it was somewhat of a disappointment to me that this never eventuated!

I have only vague memories of the day when peace was declared in August 1945. My father took my sister and me to Brisbane by train to join in the celebrations. Though I was aged eleven by then, I think I was rather overwhelmed by the numbers of people noisily thronging the streets.