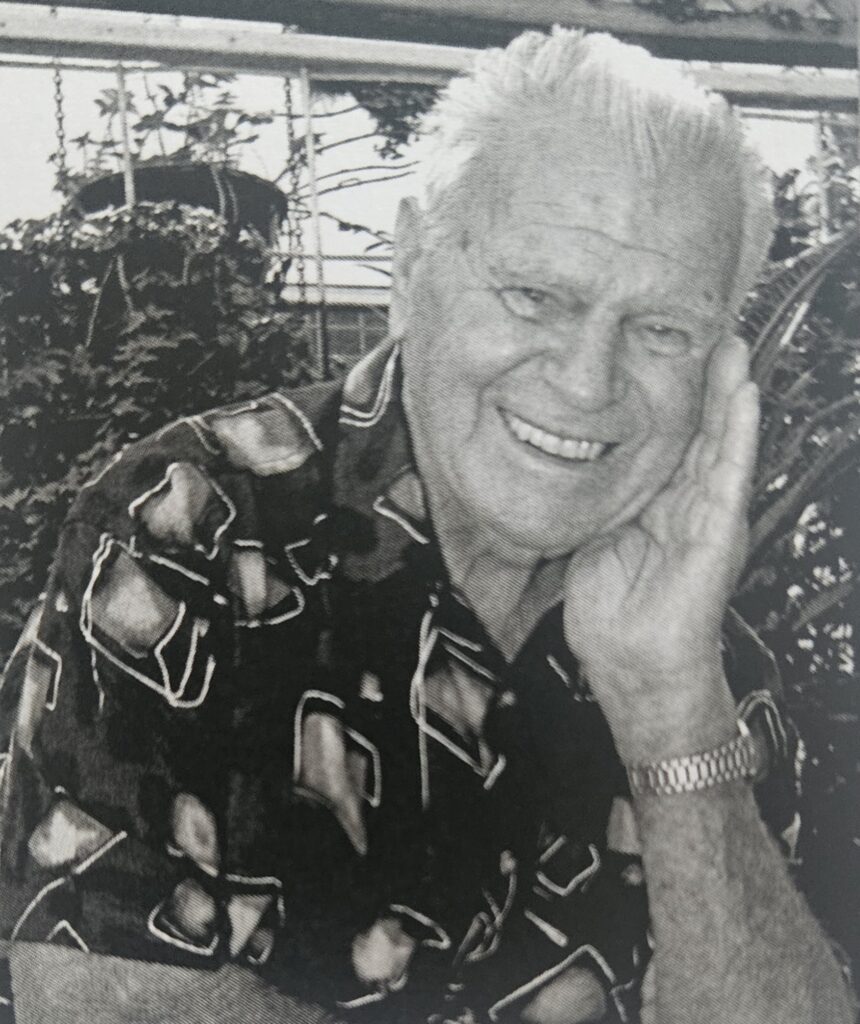

It was the early part of 1942, and I was seventeen, when the Americans came. One morning I was standing in Archerfield Road, talking to a friend, when four or five trucks came up the road and pulled up right in front of us. Dozens of soldiers got out and set to making a clearing opposite us. Curiosity got the better of me, and I was just about to enquire what was going on when an American jeep with officers pulled up, called out to the soldiers that they had the wrong place, and told them to follow him a bit further up.

They stopped at what is now McEwan Park at the corner of Archerfield Rd and Azalea St. That was the beginning of what was later called Camp Freeman. This camp largely consisted of about two hundred coloured soldiers, quite a number of barracks and 4-man tents, a mess-hall, canteen, and a huge motor pool including repair shops. An igloo-type picture theatre was added about twelve months later (others say it was totally open-air at first).

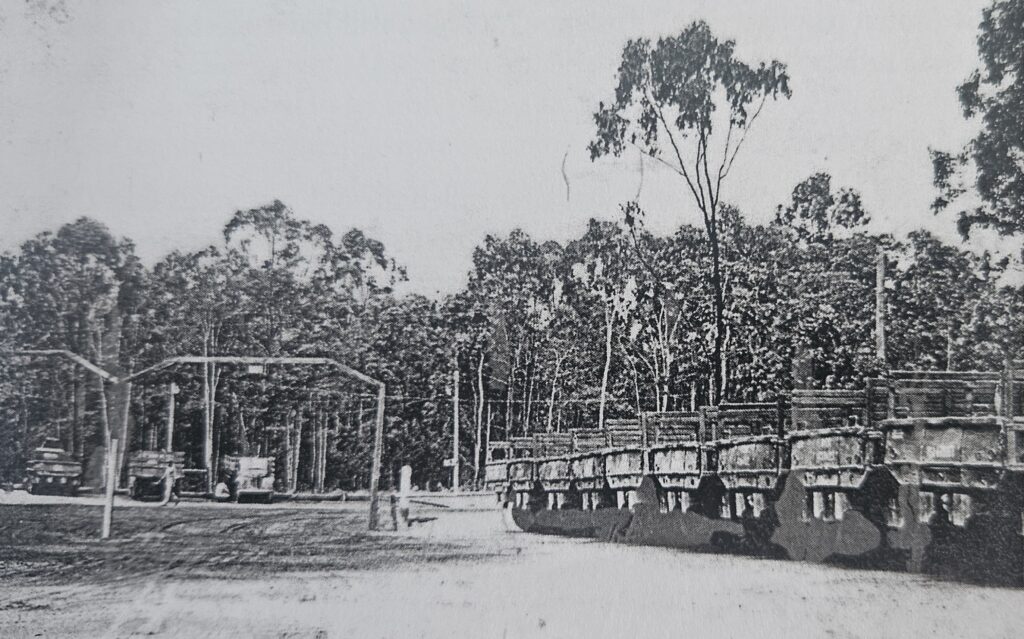

Wacol Siding

Wacol was the closest station suitable for a siding (needed to despatch the huge amount of ordnance necessary to supply the entire SW Pacific!). When the US Army approached the station master and asked for a siding, he said that “Head Office” would come out to check the request next week. The Americans could not wait and went ahead anyway, and their engineers had the siding up and running in a matter of days.

Thiess Brothers

The war really kicked them off. They put in all the roads throughout the ammo dump, and the munitions road from Richlands to Wacol. They also bitumened Archerfield Road, since US convoys continued to use it throughout the war.

Richlands

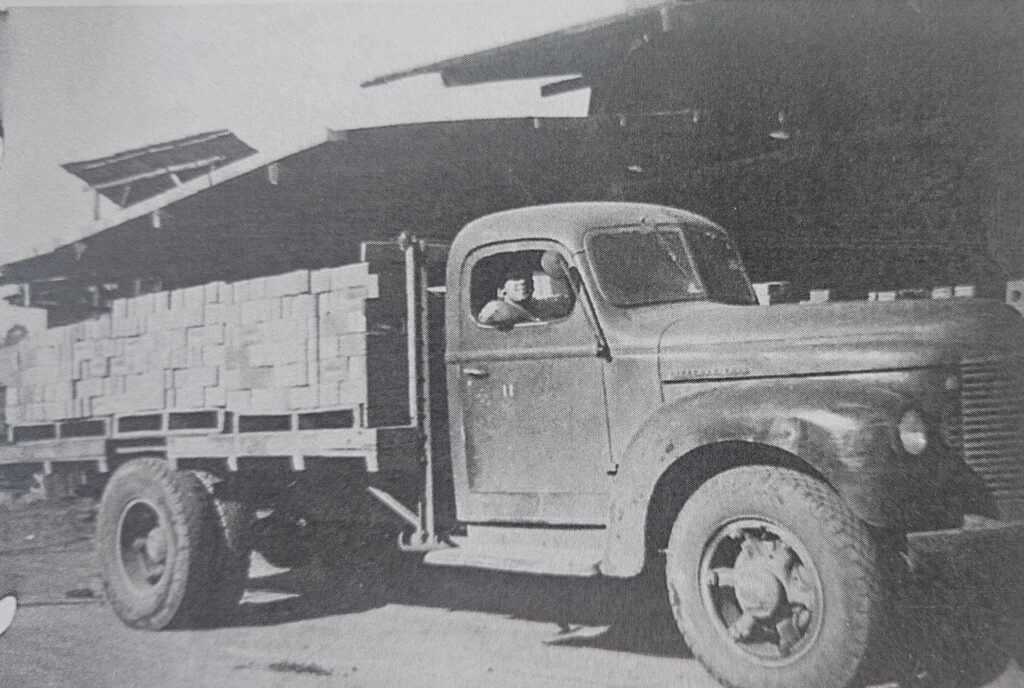

It seems to me that all incoming ordnance came by truck from the wharves, and all outgoing munitions went to Wacol and then north by train. The four Thiess brothers used to come down to have a drink at night with my brother and others—they had a camp in the bush for some time, right on the job. They started with old pre-war trucks, which often broke down. Because they had the skills for road-making, the US Army offered to provide new trucks and to negotiate a price at the end of the war. A lot of people prospered during this time.

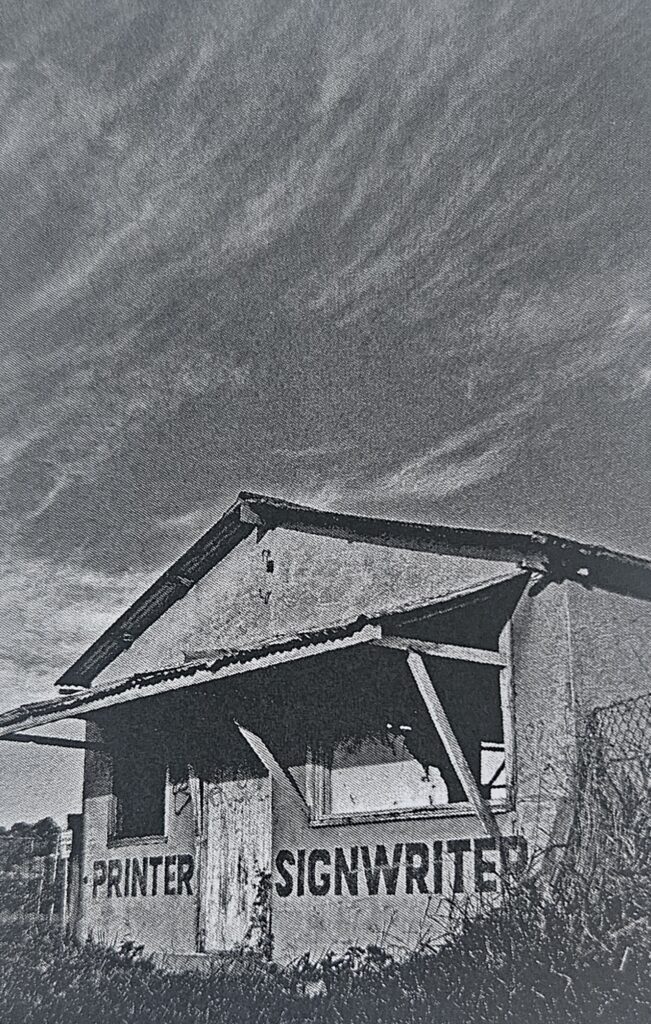

The Shop

My elder brother had the last farm before the gate to the ammo dump (Archerfield Road then finished at Government Road). The American convoy drivers were frequently stopping at the house asking for a drink as there was no water laid on—even in the camp. Though we were all on tank water, no one minded. I happened to be there one day when the soft drink man arrived. I said to my brother that he should buy a couple of cases of Green’s soft drink and sell it to the soldiers. From the first day, it was a great success! My brother added Peter’s ice cream cones (3d) to the “pop” sales, then burgers, and eventually built a small shop on the roadside. The convoys passed at all hours, and he often cooked steak and eggs at 10pm. It was a good business for the years of the ammo dump.

Coca Cola

The soldiers loved Coca Cola. The CO of the US camp gave my brother a permit to buy Coke from the factory in the Valley. Since he had to transport the cases and return the empties, my brother decided to add a penny to the cost and started charging 4d a bottle. Soon after, he received a visit from the CO, who told him: “The price of a Coke is 3d! Either you charge 3d for a Coke, or you will have no Coke to sell.” The price was reduced instantly!

More Shops

In 1942, Ned Scalia built what was later called the old Richlands Post Office in Archerfield Rd—200 metres from the Camp Freeman gates—as a shop selling to the soldiers. His was basically a chook farm then, and he sold fried chicken to the troops. He only had a horse and buggy, and he used to drive that poor old horse all the way to West End to the Peter’s factory to pick up ice cream. And he used to take the cart over to Camp Columbia in Wacol to sell there too.

Trucking

About 1942, I took over my brother’s ice run, delivering to the local families, and when the Americans came I added Camp Freeman and Camp Columbia to my run. That was in the morning; each afternoon I helped my father on the farm, especially with deliveries. One day in 1943-44, I was driving along Ipswich Road, taking a truckload of watermelons to the market. An American Army truck came up beside me, so I moved over and slowed to let him pass. But he just stayed beside me—fast or slow. Here we were, travelling two abreast on a fairly busy road which had just one lane each way! I yelled, but he just grinned, and stayed beside me. When I looked in the rearview mirror, I realised why. Two soldiers were leaning over into my truck, with their mates holding onto them so they wouldn’t fall. And they were passing watermelons back to the men in the back of his truck!

The Walking Stick

After Italy entered the war, the young men of the district made it hard for us—at least for the Italian young people (I was sixteen). We were called “Dago” or “dingo” and pelted with stones when shopping at Darra—even by boys we had gone to school with. One night I got off the train after going to the Sherwood pictures. The Darra boys were there—about 12-15 of them, wanting to fight. Eventually, I said I’d fight just one of them. Maybe because I was so wound up, I started to do too well. Things were looking bad for me when an elderly lady came along and took to them with her walking stick, hitting some on the head and yelling, “You call yourselves Australians, ganging up and all picking on one fellow.” They stopped, and I grabbed my bike and went for my life. She really saved my bacon, and the next day I went round to her house and thanked her.

Aliens

My uncle, who lived in suburban Annerley, was interned for no particular reason. My father kept saying, “He did nothing, knew nothing! So they will come for me for sure: we live close to the gates of a huge US Ammunition Dump!!!” But they never did. The police came, but they only impounded Dad’s shotgun and my .22 rifle. Everyone had a gun then, and most were good shots. My dad would aim his rifle out the kitchen window and pot the rats that dared into the yard from the chook pens. But without the guns, the hare population exploded—and we had to devise intricate hare-traps to save our beans. (During the war, guns were confiscated from all the Italians, but when the war finished all guns were returned. We were glad to get them back). Then when I turned eighteen I was called up. But I was needed for the farm work, and was exempted for that. My father was happy. He had been in the First World War, and he said, “War is not a good thing: if you take my advice, don’t volunteer to go to war.” My cousin from Annerley was called up too. But he refused to become a soldier and said, “If my father is interned because he is your enemy, then I am an enemy too!” He spent a lot of time in and out of the brig at Redbank camp. My father had put up a huge radio aerial—about 20 ft high. Concerned about family in Italy, he tried to pick up Italy by short wave radio to find out what was going on there. He did receive Italian stations a few times, but there was so much static and interference he couldn’t make sense of it. My mother did washing and ironing for the Americans. She ended up with an assortment of unclaimed keys—and after the war, when I bought an old Harley Davidson (American surplus), I found one to fit from her collection.

Internment

One gentle fellow was interned from the start. I suppose it was his own fault in a way. When the police came and told him of the 6 pm curfew, he explained that he lived and worked alone, and that his only human contact was to visit neighbours at night. “Like tonight, I am going to that house over there,” and he pointed to a house 200m away.

He went that night, the police were waiting, and when he walked out the gate they took him away! After a long time in Enogerra, he was sent to a Tasmanian labour camp—then called the CAC (Civil Aliens Corps). After a time, he found it so freezing he complained—so they sent him to Alice Springs, working in the heat—from one extreme to the other. When he eventually came home to his land, he had to start all over again. He never really recovered.

Mortar Fire

Warplanes were fitted with a device which sent out smoke—so they could be found if they ditched in the sea. One night in 1945 some of those stored at the ammo dump got wet and ignited. A couple shot into a mortar storage area nearby, and some of those started exploding—sending others into the air in all directions—Boom! BANG! Some of the fallout went through the roof of one of the farmhouses—the house nearest the camp gates. The Fire Brigade came from Corinda, but they were stopped at the dump gates—there was nothing they could do but watch the fireworks.

After the War

During the later part of 1945, the Americans had to get rid of surplus munitions. A large quantity was shipped out and dumped at sea in Moreton Bay, and a lot were exploded in large pits approximately two miles south of Richlands. The noise of these explosions caused some nervous civilians in Richlands to scream. Windows rattled, and thousands of chooks squawked and cackled. After the war, some Army surplus was sold off. I bought a .303 rifle. It was too powerful for me, so I gave it to my cousin in North Queensland to hunt feral pigs. Over a period of time, I bought three Indian motorcycles and three Harley Davidsons, which I reconditioned one at a time and sold. I bought a large toolbox too, with open-end, ring and socket spanners and many other tools, which I sold just recently. As well, I bought a 1942 three-ton Dodge truck: I used it for my ice run after the war.