I was born in November 1931 at Lady Bowen Hospital in Brisbane, the first of four children. My parents were living in Woolloongabba (Balaclava St) then, and they saw the ads for cheap land at Richlands Estate in the local Agent’s window.

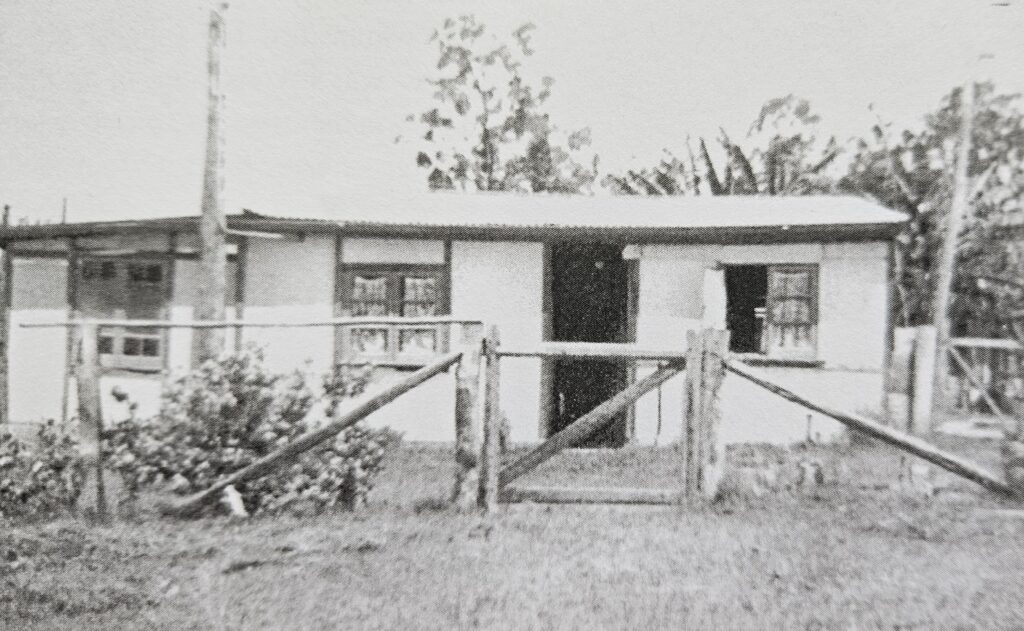

So, I was just twelve months old when we moved to our bush block at Richlands, on the corner of Garden Road and Progress Road. There was nothing there! For some time, we lived in a tent. It must have been hard for Mum with a toddler, and not even basic household facilities.

The Carter and Dabelstein man came to collect the mortgage payment—, I think. I suppose he did the rounds of Richlands Estate collecting from everybody every month. We kids always noticed because a car was an unusual sight in Richlands then. Dad often did Relief Work during the Depression—he was frequently away working on road gangs.

HOME MADE

My father was very handy, and he cut and split timber from our land to make the frame of our house. He mixed cement – and later he made bricks. So, he gradually improved the house over the years.

Dad made toy prams and cots for us girls: Mum made the rag dolls to go in them. I remember a pull along toy which was simply a tin of stones with a wire handle. We did lots of pretending, like using leaves as money – it’s a pity the kids today don’t use their imaginations so much in play.

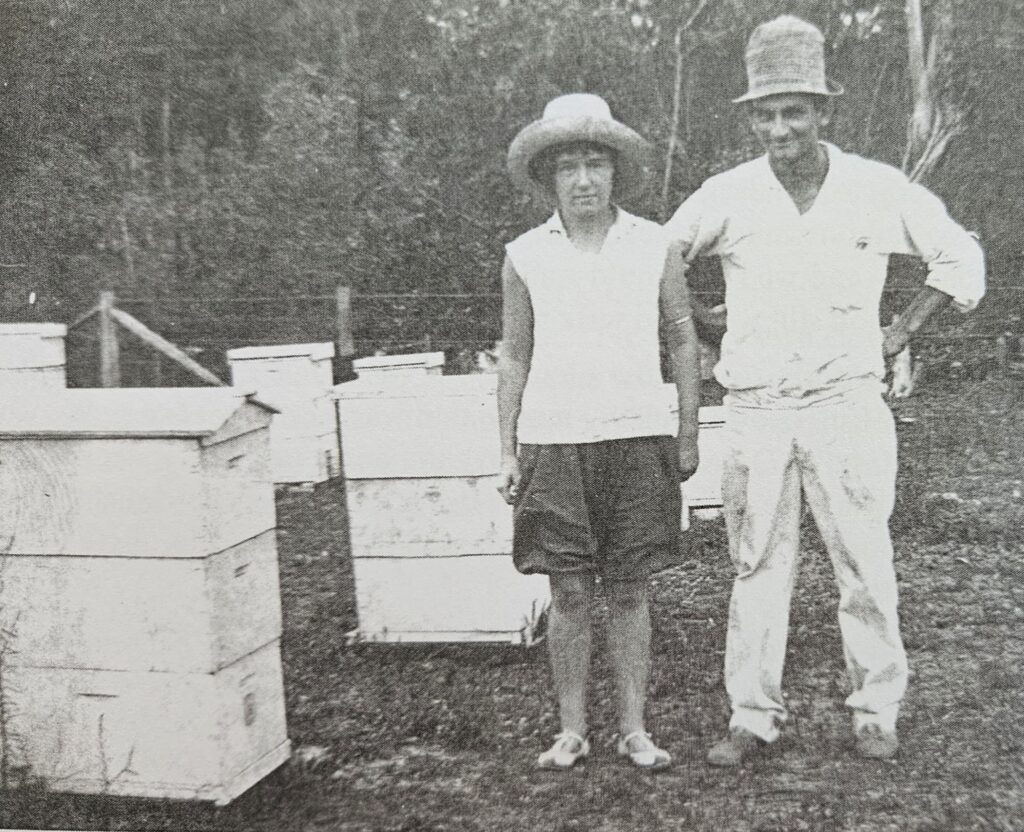

Dad kept a vegie garden when he was home. And he loved his roses. Mum was no gardener, but our neighbours were Italian market gardeners. They invited Mum to take whatever she wanted, but she wouldn’t. So, every so often we would open the back door to find a big box of fresh fruit and vegies on the doorstep. Gordon Keith and his son Donald kept their bee hives on our land – twenty or so I reckon. We would watch him smoke out the bees to collect the honey, but we kept our distance. He gave us lots of free honey.

We of course had chooks and their eggs, mandarin and orange trees, a banana clump and a beaut mulberry tree – it provided jam and pies for the whole neighbourhood. Up around Archerfield Homestead there were old Mango trees: they lined the driveway which ran off to the right-hand side of the house, and all the kids would go up there for a feed. We would climb all over these old trees. And on the way there were guavas – enough for Mum to make jam.

We all helped to chop and stack the wood – cut from our own land. In winter, we would gather around the wood fire for warmth, sometimes cooking toast on the flames, or making holes in cakes of soap with the hot poker. We had two tanks for water, but it sometimes ran out. And if a frog got in there and died, we had to drain the tank: this happened a few times. Then we had to cart water from the creek in the land opposite.

SEWING

Mum and her sister made all our clothes. (Mum had worked in a clothing factory in Stanley Street; she caught the tram in from Clayfield. So, she could make well). We had a treadle machine – a Singer, I think. Years later, after I started sewing too, we put a motor on it. One of Mum’s friends knitted for us – and when Dad was away up north, she taught Mum to knit.

By the time I was twelve, I could sew, and at fourteen I left school and started work in a factory that made frocks. From then I made my own clothes. My job at Goldman and Son was in town, at the corner of Edward and Mary Streets. I had to leave home at 6.30, ride my pushbike to Darra (5 kms), take the train, then walk through the city. I finished at 18 minutes past 5 and didn’t get home again until after 6.30pm – a twelve-hour day!

WASHING

At first Mum had washed in Kero tins, but later Dad built a washhouse, with a fire under a copper boiler and cement tubs. Mum would boil up the clothes, then rinse and blue them (with knobs of Reckitts Blue) in the troughs. She had clotheslines and props all over the yard. We kids had to bucket the water to the washhouse. Two of us would carry a kero tin full on a pole. This water came from the creek – the drinking water was too precious to use for washing.

And then we recycled the water for our baths! We had a set of 3 bathtubs – the deep tin ones with handles – and after the washing was done, we bucketed the water into the biggest one. The water was lovely – warm and soapy. The washhouse wasn’t so warm in winter – there was no door and we used to hang a blanket to stop the cold.

ANIMALS

Wallabies were commonly seen in the area then. The Brumbies were further out.

There were plenty of snakes around. Once there was a red-bellied-black up on the wooden frame that held the mosquito net over Mum’s bed. Somehow Mum got rid of it – I think with a knife. Another time I was scared by a snake crossing the back doorstep. But it turned out my brothers had tied a string around a dead snake. Boy, it stank too.

We always had cats and dogs. One cat we would dress up in doll’s clothes – and even the dog would drag her around, she was so placid. Only Mum milked the cow. We had one called Mabel. Every so often she would escape – looking for a husband – and we kids would walk miles searching for her. She had a bell, but if she stood still we could walk right past her in the bush.

Dad had a workhorse for the plough, but we didn’t ride him. And later I remember Mum drove a sulky – maybe that was a different horse. We would all pile in to go to Darra, and she’d leave the horse near the water trough by the station while we shopped. Once she drove us all over to swim at the beach at the Indooroopilly bridge. We took a picnic – you had to, there were no takeaways then.

SCHOOL

I started school as soon as I turned five – for just the last few weeks of 1936. I loved it from the first. Richlands school then had two rooms – on stilts with concrete underneath. Cook Street ran beside the school. This was later extended and became Orchard Road – proof is that Cook St appears on Gerry Gillespie’s marriage certificate.

I had the same teacher throughout my school days: F C Cooper. He lived at Eagle Junction, and every day he caught the train to Darra, where he kept a bike in a shed, then rode for three miles – and he only put on his tie when he got to school. At the end of the day, off would come the tie and out would come the bike.

We lived close to the school, so it was easy to walk. Some lunch times we would walk halfway home to meet Mum. She might bring us something she had just made – I especially remember hot potato chips on a cold winter’s day.

Richlands pupils invented a game we called “Beam,” played under the schoolrooms. Each player had to bounce the ball up onto the beam above, then catch it without dropping it. We all counted. There was also Vigoro and Rounders, and the boys played Marbles – and Brandy too! We had a basketball (netball) court, but only once do I remember another school visiting to play us.

I did Year 7 twice – the only other Year 7 student did Scholarship, which had just come in. Each week I travelled to Milton State School for Domestic Science. We had rotating classes of Sewing, Theory, Mothercraft and Cooking. I had to be very careful bringing what I had cooked home – tied up in a tea towel – on my push bike from Darra.

THE SCHOOL COMMITTEE

Mum was on the School Committee, and the ladies would often gather at our place – maybe to sew for the school fete over a cuppa. I remember Mum copied a pattern for a stuffed panda bear and made dozens for the school fetes.

I learned to dance at weekly dances the Committee held at the school: the music was played on the school’s gramophone. Most local families went. Some (like Mum) played Euchre on the veranda: I remember the smelly sulphur lamps out there. The kids milled around, and then we all had supper under the building (everyone brought a plate). That was the Friday night community social contact.

The end-of-year outing to Shornecliffe was a favourite. The school reserved a carriage on the train – and each year there was trouble at Darra Station when we found others were already in “our” carriage.

Pino Zeriotti’s dad was always waiting at Shornecliffe with a truck full of watermelons and pineapples from his farm: there was a lot of sharing in the community then. All day we would swim and play organised games, and the school committee supplied lunch – sandwiches, I think. Just before we left, we would line up for a bag of lollies – with plums and apricots too. The committee had to look out for ring-ins – all the kids on the beach wanted a lolly bag. Then on the train on the way home we would munch our goodies, sing songs – and the young ones would fall asleep. It was a great end to the school year!

MEDICAL MEMORIES

My younger brother and sister were home births. I seem to remember the midwife coming when my little sister was born: Dad took the other three of us up the paddock with him that day. Doctor Buchanan (son and father) would come to the house if you were really sick – but I don’t remember them coming to our house. A day in bed was usually all we needed.

A dose of castor oil was common. Antiseptics were Gentian violet and Condes crystals in water – and they stained everything they touched. For colds, we were given a spoonful of sugar with a drop of eucalyptus, or cough medicines that Mum would make up from a mixture called Heenzo – the Vicks Vapour Rub came later. Mum bought medicines from the travelling Rawleighs man.

Everyone got measles and mumps – and one year whooping cough went through the school. When I was twelve my mother took us in to City Hall for the new, free diphtheria vaccinations. But we had fresh food, fresh air and plenty of activity – and we were strong and healthy.

FREE TIME

We played in the bush – Mum never knew where we were. And we all had push bikes – so we rode everywhere. My brothers loved Cowboys and Indians – and were forever fighting over who wouldn’t “lay down dead” when “shot.” We would sometimes catch lobbies in the creek, using a length of cotton and a bit of meat. We would light a fire beside the creek, boil a tin of water, and cook and eat them there.

SHOPPING

Each week, Mum would walk to Darra – pushing the big cane pram on the unmade roads – to order the groceries: they would then be delivered by car. The Baker and the Iceman delivered to the house. We also shopped locally sometimes at Brown’s store on the corner of Freeman Road and Archerfield Road – not a very big shop, but it had the extras you wanted. The shop was often shut, because the owner was up at the house drinking.

The Americans

I was ten when the Americans came, just a schoolgirl.

They were a bit cheeky. They blocked off Government Road, and the Bull’s had to have a pass to get to and from their own house! There was a sentry box just down the road from us, and when Dad left the VDC (Voluntary Defence Corps), he needed a pass to get to his job at Goodna Mental Asylum. And they just took a triangle of Dad’s property to put their road through to Wacol.

But the soldiers were friendly, giving the kids chewing gum, and chatting to us. Some visited private homes. We never felt threatened. Some of the older girls were smitten, and a couple had soldier babies. Of course, the girls weren’t sent away (only posh people did that) – and the babies were kept in the family.

Old Scalia ran the “old post office” shop in Archerfield Road, though it was on Mr Stanley’s land. He sold mainly to the Americans – he didn’t want to serve the locals!! My girlfriend’s sister peeled the onions for his hamburgers. I remember Coca Cola was 3d a bottle then – and I still have an empty bottle.

We certainly had ration cards during the war, for sugar, tea and clothing – but I don’t remember shortages. Mum used her ration cards at Darra. We were pretty self-sufficient – and maybe we had more ration cards than money.

We often went to the pictures at the American camp at Azalea Street: I remember “Dumbo.” We also went to the matinee at Darra at times – when Mum could afford it.

Dad had always been away a lot, so nothing changed for me when he went north with the VDC. He went to Port Moresby, and Daru Island in the Torres Strait (just off the southern coast of PNG) – into a war zone, though the VDC was for home defence. Our news was frequent letters from him – with holes cut in them by the censors. Mum didn’t get the newspaper. We had a crystal radio, then later a mantel radio which was kept on a shelf: the battery was put on the carrier of the pushbike to take to the garage to be charged.

After I started work, our haunt was the dances in the building opposite Central Station: we went twice a week. I knew people there, and the only servicemen were some from the Air Force base at Amberley. We could pal up with one of them and chat on the train on the way home – then wave them goodbye at Darra.

I went to a few dances at the Darra Hall – it was also the Darra Picture show! But I don’t remember any Americans there, so it must have been after the war.

Even the local evidence of war was of no concern to teenage girls. So for me the war years came and went without much effect.