My father, Bill Eason, was born in Highgate Hill in 1886. Mother was born in England in 1890 and came out in 1909. They met and married in 1911.

My father and his brother Len took the train from Indooroopilly to look at land in Darra in 1914, when the first advertisements for town blocks appeared—1/4 acre blocks were £5 then. Unmade roads were newly cut through the bush, but that was all that was here. Then, from 1915, my father worked as a fitter and turner at the Ipswich Railway Workshops with Percy Dyne. Dad had served his apprenticeship at the British India Co at Kangaroo Point with Percy, who had a lot of land—including a quarry—in the Darra area. Bill Dyne’s land on Ipswich Road was taken for part of the US Camp Columbia. And it was on Alf Dynes’ 400 acres in Richlands that Serviceton—later Inala—was established. Eventually, my parents moved to Darra in 1923 and rented first in Scott’s Road, then a little red house at the corner of Balfour and Winslow Street. Both houses were owned by Percy Dyne. I was born in 1924 in a nursing home in Hamilton, close to Mum’s sister. My sister was born three years later, in the red house in Darra, with Nurse Burns in attendance. (There had been an older brother who died aged two, and a sister who died of diphtheria at nine). In 1929, we moved to this house, and I have lived here for nearly eighty years. The house was originally built in Orchard Road, Richlands, in 1916 I think, by the Seddons. About 1921, they moved it here—in pieces I should think—and sold it to my family in 1929. I added the front section much later, in 1977.

Darra School

In 1929, I started school at Darra. Mum said she was very pleased with my first school report—”Place in class – 3.” That was until she read the next part—”Number in class – 3.” I’d say there were about a hundred kids at the school. A few walked over from Richlands, and more caught the train from Wacol. One or two were driven in sulkies (there were no cars then), but most walked or rode bikes. In the summer storms, flooded creeks kept some at home—and others stood under the school downpipe so they would be sent home! (We lived right opposite the school, so I didn’t miss many days at all).

I remember the annual school Fancy Dress Parade in the local hall. We marched around, and Mrs. Cross played the piano. I remember dressing as Robin Hood, and I recall a costume labeled “Why did I kiss that girl?” The boy was covered in sticking plaster. My mother was on the school committee, but she was not a good fundraiser. Once, to try to raise a shilling, she (with others) set off with a cartload of pumpkins to sell. She came back with an empty cart—and only 1½d! At times we saw silent films in the Darra Hall—with the pianola providing background music. The music was often inappropriate—I remember an exciting charge of the Indian hordes on screen—and the pianola played a slow death march! The accompanist was Gladys Drew. When I was about nine, there were two epidemics that closed the school. First, diphtheria went through the school—and one local girl died. The authorities swabbed the whole school, and found six carriers: I was one of them! We were quarantined in Wattlebrae Infectious Diseases Hospital at Royal Brisbane for three weeks. Then a polio scare gave us ages off school—and Mum made us gargle with Condy’s Crystals daily. We didn’t get polio. Cars were a rarity. So it was exciting when Mr. Bishop, the baker, drove four of us to Ipswich on Saturday mornings for Scholarship practice. He had a phone too—only businesses could apply then. That was in 1936.

Ipswich Road

Most local families had a cow then. Each evening I would bring five cows home over Ipswich Road—you couldn’t do that now! We paid 10/- a year to the BCC, which entitled our stock to roam freely—and I had to find them and bring them back for milking. The Cliffe family owned the others: I brought home whatever cows I found, but I only milked our own cow. Ipswich Road was also part of the stock route from the Darling Downs to Brisbane. The stock route was as old as the road I reckon. We would hear the whips cracking and the dogs barking, and all the local kids would rush up to see the mobs of cattle and sheep pass—en route to Foggett Jones Hutton (who had holding yards at Oxley) and/or to Cannon Hill saleyards. But I didn’t see these droving mobs after about 1932-33. (Brisbane was still a country town not so long ago—I knew a man who drove cattle from Newmarket down Queen Street to Cannon Hill).

Ipswich Road was a single lane then, with deep earth gutters on either side and only the occasional car. The Wacol-Oxley stretch was the last to be bituminised, about 1926—and the families of two men who worked on it lived in tents on the Darra Recreation Ground.

Darra Before the War

Local Employment

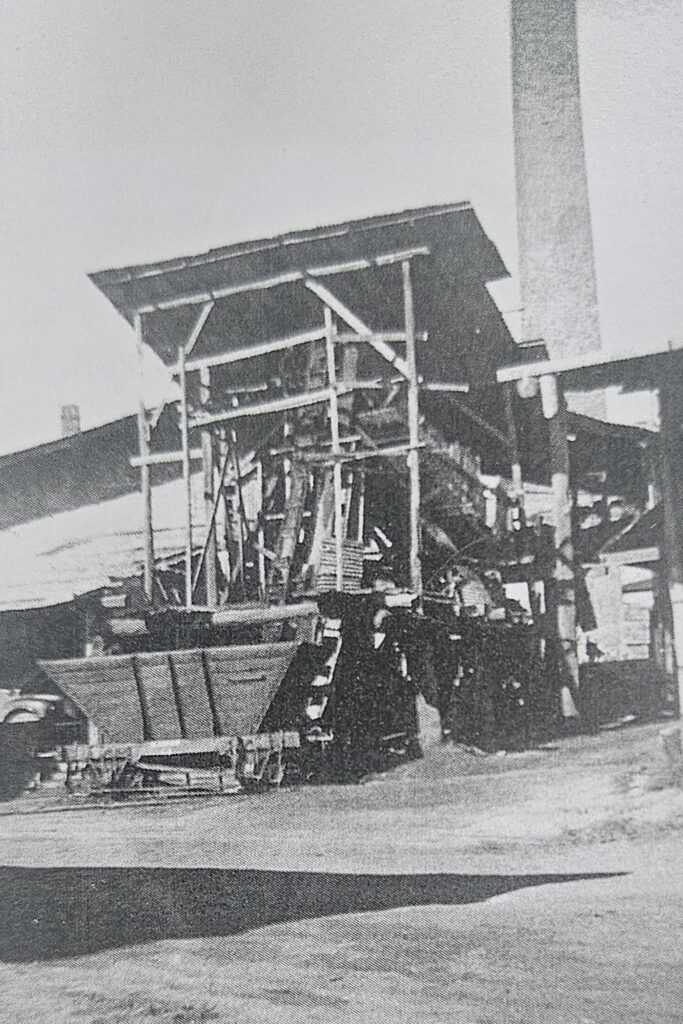

Darra was a workers’ settlement. Many men worked at the Ipswich Railway Workshops, Goodna Asylum, or the Redbank woollen mills or meatworks—and a few girls worked in city factories and offices. The married women stayed at home. Without the mod-cons and takeaways of today, there was a lot to do to look after a house and family. And also—men would be tormented at work that they were “too miserable” to support their wife. It was only the manpower shortages during the war that sent the women out to work. In Darra, there were the Cement Works, Brittain’s Brickworks, two sawmills, and a small foundry. There was also a charcoal burner. Steve Noble (from Goodna) had lost a leg. He wore an old wooden one that he made himself, and he would go out alone and fell the trees, and cut them into six-foot lengths. He would burn the timber, then pour water on at a certain stage to make charcoal. This was covered with sand to cool—all in the bush. Then he would bag it and load the truck. At Darra, he would grind it and sell it to be used in chook feed—and during the war for car fuel. There were some farms—over along the river mostly—and everyone had a vegetable garden, chooks, and a cow. About 1930, there were just three or four shops in Darra—a butcher, a bakehouse, and two grocers. For a time there was a hairdresser’s, but most families cut their hair at home so it didn’t last.

Darra Station

The station had two platforms, a ticket house, and the Station Master’s house, which was right by the crossing gates, next to the footbridge over the line—which none of us used. Passenger trains were made of first-class wood—often cedar or beech—there was a lot of work in a carriage. I think Brisbane/Ipswich trains ran every half hour—at least in the peak times. I didn’t travel to Brisbane until I went to Brisbane Grammar School (1938-39)—and I had a free train pass to go to school.

The Cement Works (the only one in Queensland) had a branch line—always with wagons lined up. At the station siding, there was a ramp for loading and unloading logs into the railway trucks. I remember silky oak coming in from North Queensland to Scott’s sawmill. The Brickworks had a siding too for a time, but trucks were better for them. During the Depression, old Bill Brittain, rather than putting men off, had them fill in the trench dug for the siding with unsold bricks. Then, when there was a shortage during the war, he dug them up and sold them. He was a real “captain of industry”—he led his workers. If a 14-year-old boy was off sick, Bill would take his place on the line. Bill Brittain was a character. With his braces and beard, he didn’t look like he owned a brickworks. There is a story that he went to town to buy a new Ford truck for the brickworks, with cash for the full cost in a sugar bag! The people in the Ford car yard ignored this eccentric old man—so he walked down the road and bought a big International. During the Depression, there was a lot of unemployment, and many men did relief work. Much was in the local area—on roads, etc. There was a big project at the school—the men worked for months, terracing the grounds with pick and shovel, horse and dray. The dole was 4/6 a week. At the Railway Workshops, my father was cut to three days one week and two days the next. It must have been hard on the parents, but we didn’t seem to go without.

Swaggies

There were swaggies about then, old Sundowners with big beards. We had bought the vacant blocks on either side, and on one, there was a big ironbark stump that the swaggies—often three or four—would light their fires by. They would knock on the door and ask for “a spoonful of tea and sugar please, Mum.” When I woke up the next morning, I would look out to see them rolled up in their swags. They were always gone by 9 or 10 am. But they seemed to have a circuit because we saw the same fellows two or three times a year. My one regret is that I never took a photo.

“Dan Kelly”

Every so often, I suppose when I was nine or ten, word would go around school that “old Dan Kelly” was camped up at the Recreation Ground. We would all go up and gather round while he told us of the Kelly’s Last Stand. He said that after the fire at Glenrowan, relatives secretly found him and nursed him back to life. He certainly had terrible burn scars.

Years later, I met a young fellow in a Christian group I was supervising who was the spitting image of old Dan! I thought, “By Jove, these two must be related!” His name was Earl Quinn, and his mother Hannah—a lady who wouldn’t lie—told me that her husband was related to the Quinn branch of the Kelly family. Neither man looked like the photos of Dan I have seen—more like Ned—but because of Earl Quinn, I would certainly believe that our “Dan Kelly” was related to the Kellys.

World War II

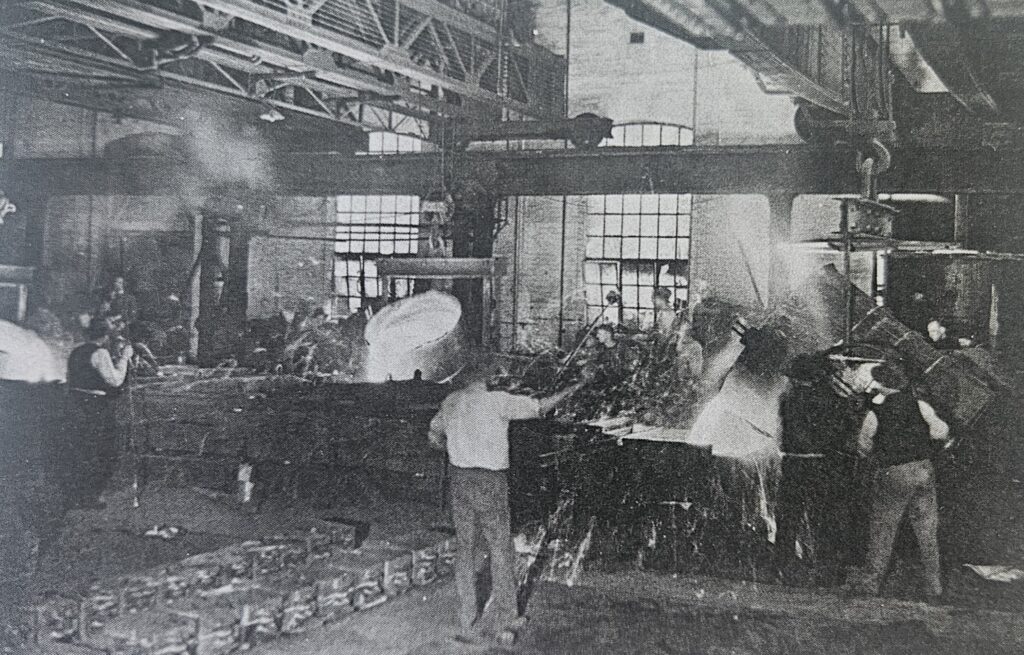

When I turned fourteen, I left school and started work at Burgess’s foundry up near the brickworks. The building is still there. The foundry produced brake blocks for the trams, mill loading for the cement works (like large ball bearings, used to smash the coral), and brass bearings. Every night I came home exhausted. It was hard work, but we used to sing at the foundry. How many people sing at their work today? That was in 1939—and that was also the year that the war started. My parents had been through WWI, so they were not keen to dwell on it. We had no wireless then, and any news was clearly heavily censored. And since the war was a long way away, I gave it little thought at first. I remember there were real shortages of materials for the Army. Soldiers often trained with wooden guns, and a joke was “Halt—or I’ll fill you full of white ants!” When I was 15, I became the full-time grocer’s boy at McSwan’s in Darra. I would serve, pick up orders, and two days a week would deliver on my bike—as far away as Richlands and Wacol. But on Fridays, I would have dinner at work, then with Mr. McSwan, we would deliver the big orders in his truck. I remember he bought a great new truck—a Chev ute with the new column gearstick. His brother-in-law (home on leave from the Army) took me for a spin—and we did 90 mph—the fastest I’d ever travelled in my life! But the military commandeered the Chev, and replaced it with an old Dodge.

Soldiers in Darra

Local men enlisted—some automatically because their fathers had been soldiers, others for the adventure. And some were conscripted. Cousins and neighbors all went—and soon most of the local young men had gone—and at least two never came back. My first experience of the US Army was one day early in 1942 when I was visiting over in Richlands. I saw a huge machine—my first bulldozer—tearing roads through the bush. Camp Freeman would be black, but these men were definitely white. Maybe they were engineers laying out the ammo dump. By then I was seventeen, and soon I received my call-up papers. I was passed as medically fit, but then when he saw my trade, the officer said, “Get out of here! Don’t waste my time!” I was in a wartime Essential Industry—and they even brought men back from overseas if they had skills that were needed for the war effort. Parts of the district were appropriated by the government for the Forces, like Scott’s 400 acres at Richlands, and Bill Dyne’s house and land on Ipswich Road. The US Army ended up with 8-10,000 acres. The war brought a boom in demand for materials and equipment. The cement and brickworks took on more men, and small businesses benefited too, from both the locals and the soldiers. One fellow I knew was asked to provide a ton of carrots a week to the US Army. Ipswich Railway Workshops made munitions for the war effort. Munitions trains from Wacol clanked through Darra day and night at times. The trains did a mighty job during the war—they were the only reliable transport we had to cover the country. Darra was the closest station for troops from Camp Freeman to go to the city. The US soldiers didn’t walk to and fro—they always had plenty of trucks and equipment. And the soldiers had no rationing at all, while civilians were severely rationed—for petrol, tea, butter, meat, clothing, etc.

Shootings!

American MPs were certainly Gung-ho. As I remember, a few were colored—and they all had guns! We heard gunfire every so often. They were quick to shoot into the bush—and to hear a dingo howl for the first time would certainly scare anyone! It seems to me that the soldiers were city boys—more scared of the bush at night than of the MPs. There are stories, but I never met anyone who actually saw an MP shoot a soldier. But I did experience the fear of the MPs one night. I was home alone when there was a knock on the door. A terrified Negro with no shirt on pushed past me into our house. “The MPs will shoot me,” he said. Not long after, a couple of white Yanks walked in and searched around, poking under beds and yelling, “Come out, Nigger.” They found him outside behind the Queensland nut tree, and took him away. Whether they shot him I don’t know, but he certainly thought they would!

When my parents came home that night, they told me that there had been a brawl, so what the story was I don’t know. I do remember another big stoush in Darra—between the black and white Americans. But then, a fight could start in Brisbane and end up in Darra. Darra was declared a black area by the US military authorities in a bid to separate their warring soldiers.

Anti-American?

Certain people in the community were anti the US soldiers—black or white! But I like to remember Peter, the Aboriginal blacktracker from the Oxley Police Station. He was as black as the ace of spades, but here he was complaining loudly about the Negroes. Some people are never in doubt—but often wrong! Certainly, there were some local people who would have been intolerant of angels. And wartime is a difficult time. There were endless uncertainties and restrictions, and these brought frustrations and resentments. In addition, Americans have a different culture. There are many similarities, but also many differences. And this caused problems too. The Americans were certainly an overpowering presence at that time. But really, it was for a very short time—they were gone in two years. And in the end, we thought—better the Americans than the Japanese!

Fraternisation

When two Negro soldiers knocked on our door (they probably knew my 16-year-old sister lived here), my mother welcomed them and invited them in for afternoon tea. They were polite and charming. But when they said that they would visit again, Mum put them off. When I asked her why she had entertained the soldiers, Mum said, “If you were a soldier sent to a foreign land, I’d hope that people would make you welcome!” Racial comments would not have been countenanced in our house, and my parents thought we could at least be gracious to these soldiers who were fighting for us. But the white American attitude was, “You have undone in a short time what we have taken two hundred years to establish.” And some neighbors also were critical of Mum for inviting them in. I offended too. One night, a Negro knocked on the door and asked what he could do in Darra. There wasn’t much! But I knew there was a Card Night on at the school opposite, so I took him over there. It went over like a lead balloon. But people always have differing views on religion and politics—and this situation touched on both. No real harm was done to community relations. Young men are always chasing girls—and young soldiers more so! And young women the world over seem to like a uniform. Often the old people disapprove—sometimes with reason. So that was a source of ongoing discussion in the community. I worked in the corner shop in Darra for Mrs. McSwan. An American soldier asked her out, and as “a married woman” she was deeply offended. Then she was even more offended by his reply—”That don’t make no difference, sister.” One American soldier I came to know well. I really got to know him after the war—shooting and fishing. Russell was a Cherokee—but Indians were not classed as coloreds, so he was in a white troop—I think he was an MP. Rusty married a Darra girl, and was later discharged from the US Army and lived here. They set up a roadside shop on the Toowoomba highway—and the sign “Rusty’s” can still be seen up near Plainlands.

The End of the War

The whole nation had been engaged in the war—everything was geared towards the war effort. We had a common purpose, and so the celebrations were intense, with a deep sense of sharing. Not like today—when a few of us are at war, and many watch it on television as entertainment. The Cement Works whistle was a local signal—used to warn of escapes from the Goodna Asylum or from the Oxley police cells. We all knew it would eventually announce the end of the war. My father had told me about the excitement at the end of WWI, so when at last we heard the whistle blasting, we foundry boys headed for town. There were thousands packed into the city—for hours we didn’t move from Anzac Square. There was no drunkenness or fighting—everyone was so relieved. The surrounding fence was pulled down to make a bonfire, and the girls kissed everyone. It was great!