My father was born in Italy in 1898. (We have a photo of him at the family house in his village. When it was demolished, it was found to be 300 years old). When Pilede turned seventeen, he was conscripted into the army. (In 1915, Italy joined the Allies in WWI). He fought for two years, then became sick, was hospitalised in Albania, and almost died.

Dad met my mother in Malara. They married, and my sister Dorville was born in 1920. Dad found work in a cheese factory. (Years later, he tried to make cheese in Richlands, but it was so hard we had to grate it).

Fascism was spreading across Europe after World War I, and my father hated the anti-worker flavour of it. Later, Mussolini came to power, and Dad was known for being anti-fascist—he always wore a red handkerchief. Eventually, he was in grave danger and went into hiding. His elder sister harboured him, and she was beaten up by the fascists. He had no alternative but to leave the country. So he came to Queensland with a group of men from his home village. That was in 1925. They worked on the cane fields at Halifax, with lots of other Europeans trying to make a new life. My mother and seven-year-old sister followed three years later, in 1928—along with Dorville Zerlotti and her son Pino, who had also waited behind in the same village in Italy.

After recovering from the journey, my mother immediately started work, cooking for a cane gang of about ten men. Dorville went to school first in Macknade, then Halifax. I was born at home in 1931, and the midwife’s name is on my birth certificate—Mrs Maria Rusticalli. My mother was not pleased at first—they were so poor and worked so hard that another child just added to the burden.

Coming to Richlands

By 1934, my parents had saved enough to buy a piece of cheap land and be their own bosses. We moved down to Richlands on Boxing Day 1934. Timo Zerlotti had settled his family here, and we lived with them in their shanty for eight months. Then he sold us one of his four-acre blocks—at 99 Government Road—and we were neighbours again.

The Italians here kept in contact with those up north in the cane fields, and Mum also wrote home to Italy frequently—at least until the war. But this was their home: they had become naturalised in Halifax in 1932.

Our block was virgin land, and my parents cleared it together. My Mum was out there with Dad on the tree-puller. She helped dig the well too, using a winch. She must have wished she was back on the cane fields at times. Dad built our house himself—and all the timber came off that paddock! I think the Scotts cut the boards for him in their sawmill at Darra. He added to and improved it over the years and lived there until 1959.

This was Depression time, and the only paid work Dad could get was relief work on the road gangs—for about 27/6 a week.

Dad’s English was OK, but Mum knew very little. And nor did I when I started school. I couldn’t understand, and I would cry. The teacher would sit me outside, and I used to run away. Dorville would take me back. After the initial fear, I learned some English, and then I loved school. I made friends—like Beryl Clark—who are my friends today. We played hopscotch and rounders, and we girls often had to make up the soccer or cricket teams.

Mum never actually taught us to cook. We were always around, helping, and we just picked it up. I always wanted to help make the spaghetti, and I still have a “broomstick” to roll it on. I remember we made ravioli with chicken—and a wonderful one with pumpkin. And we made gnocchi too. Vito Pianeda often caught hares—he set traps all around for them—and Mum’s hare stew was a real delicacy!

Mum didn’t sew so much, but she knitted and crocheted very well. My sister did the sewing from the time she was ten—and I was one of the best-dressed kids in school.

World War II

I don’t remember when the war started—I was only 8, and it didn’t touch us. Then after Italy joined the war in 1940, a few kids at school called us “Dago”—but I didn’t know what it was all about, and it wasn’t too bad—I still had my girlfriends.

For a while, we were worried that Dad would be sent to a concentration camp—which was odd considering he hated Mussolini. A couple of others were taken, but Dad only had to report to Oxley Police Station regularly. But the men seemed to just shrug it off and get on with their farming and families.

The Shops

When the Americans came in 1942, I was eleven. My sister had married Jim Sparrow the year before, and she worked with his sister Beattie selling drinks and ice cream in Mr Stanley’s shop (later called the Old Post Office) on Archerfield Road—not far from her house.

Later—in 1944—she worked with Ulmer Formigoni in another small shop on Archerfield Road (corner of Littleton Road), selling the same things to the Americans. She dipped whole chickens briefly in boiling water to loosen the feathers for plucking. They then cut them in four and fried them in boiling oil. They were three-month-old chickens—very tender—and the Americans loved them.

Cantoni Family Income

My parents at last paid off their mortgage during this time. Dad made a killing one year! He was the only one who planted cabbages – and the Americans loved sauerkraut. They loved his strawberries too-by then he was growing tomatoes, beans etc too, and there was a ready market in the Army camps. Mr Zerlotti was the carrier at that time.

Mum made extra money doing American washing. She had a big boiler, which Dad would light every morning for her. And then she had to iron everything – being sure to put three pleats in the back of every shirt. I reckon my sister helped with that too. Then we’d have to fold everything, wrap it in brown paper, and label each package – 1/6 for a shirt, or 2/6 for trousers.

We went to the Americana picture show at the camp. There had to be an American at the gate to bring you as his guest. We went every week!

Richlands Rationing

There was rationing, but we always had enough food on the table. We had chickens and also our own cow, so butter was no problem. We grew fruit and vegetables, and we all went up to the Homestead for mangoes—there was plenty for everyone. But rationing did affect us for sugar and tea.

Sugar was the problem—we all took two spoons in our tea. We took to buying honey from Gordon Keith for our sweetener, then later Golden Syrup. That didn’t taste too good—and from that time, none of us took sugar.

Clothing was rationed too, but that was not a problem for us, as my sister was a great seamstress. Parachute silk could always be found—often as a gift from a soldier. It was used to make petticoats—and undies too. There was a shortage of elastic, so many of the undies had buttons at that time.

The petrol shortages didn’t touch us: we had no car, and we rode bikes to Darra Station. My sister bought the first bike in our family when she was seventeen.

The End of the War

I was still at home when the war ended, and I remember nothing of VP Day. But by 1946, I was fifteen and started work in town as an apprentice at Pike Brothers, trouser makers.

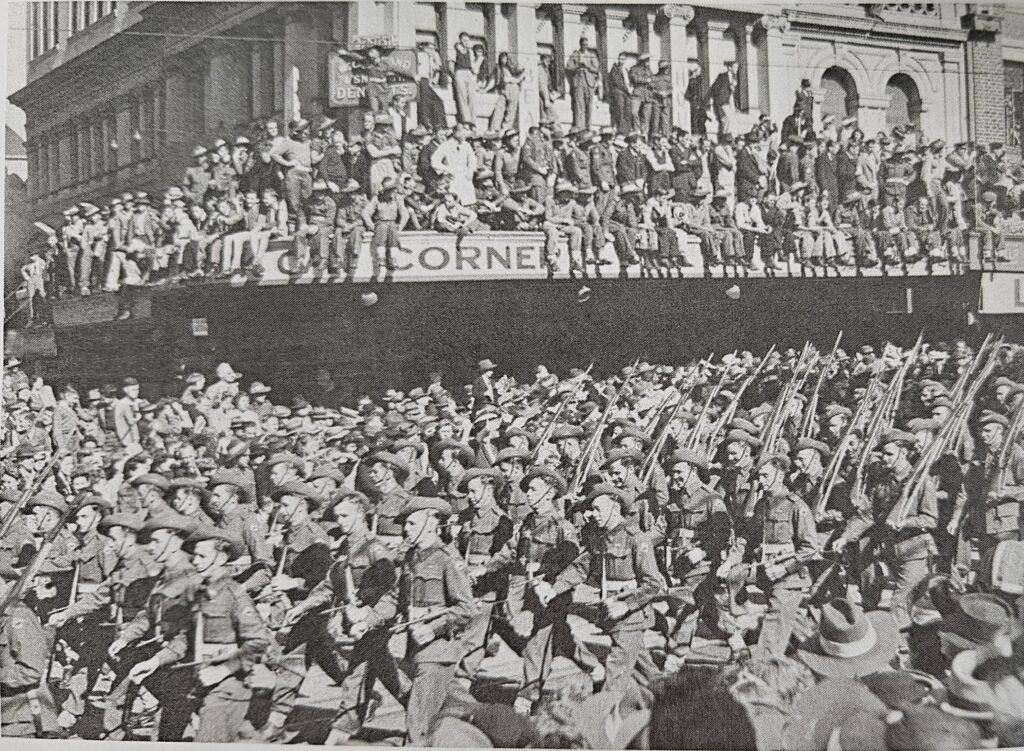

I remember as the Australian soldiers came home, they would parade down Queen Street—on foot or in trucks—and we would leave our machines and go to the windows to cheer them: it was very exciting!