The Loff Family

My mother Tilly was born in Darra on 4 November 1905. The youngest of six children, she was born at home, in a railway house. Darra was little more than a fettler’s camp then—though Brittain’s Brickworks had been going since 1899. The fettler’s houses were beyond the brickworks, near the “Nine-foot bridge”—which was really an underpass under the railway line. This house was later moved into Darra to become the station master’s house, next to the station. By about 1910, the family had moved to a farm on the river bend. Loff’s Road is named after my grandfather.

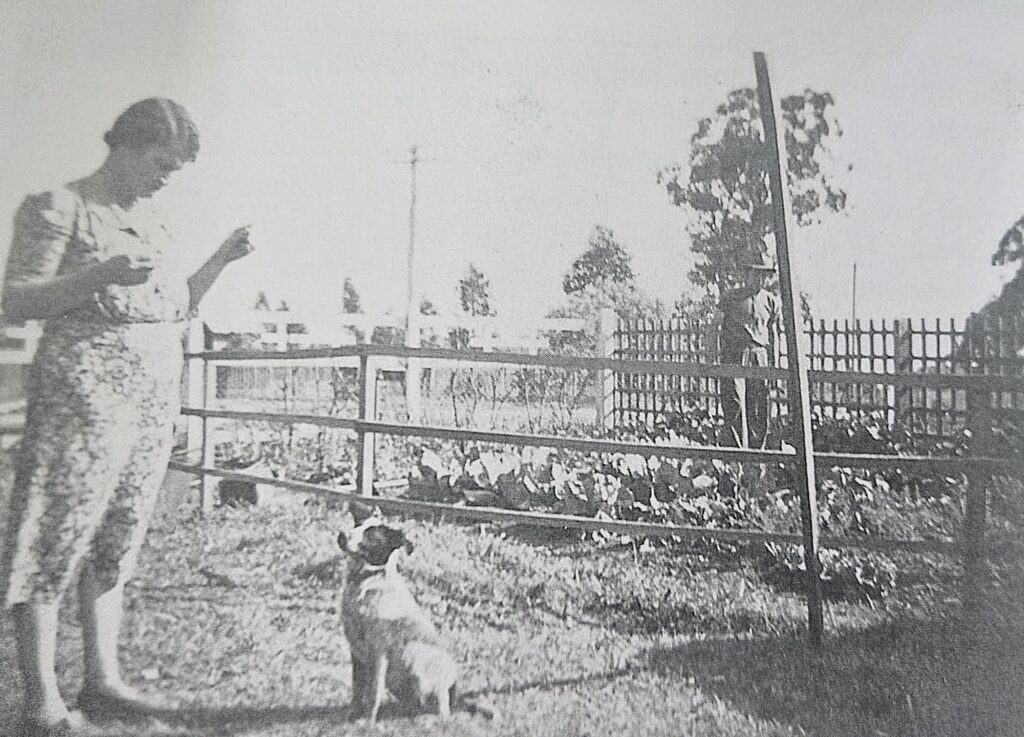

(The road ran right to the farm gate at the river then—now it disappears into the golf course at Jamboree Heights, and reappears as just a track at the river end). This area is now called Westlake, but then Darra was still the closest settlement. The closest school was at Pullenvale. My aunt and my mother would row across the Brisbane River each morning, then walk two kilometres to school. Then when her sister left, Mum stayed with her married sister at Oxley and went to Oxley school. This was her eldest sister, who married Arthur Brittain. He had a poultry farm in Douglas Street behind the brickworks. He was always “Uncle Chook” to us—and “Chook” to the whole community).

And when the Darra School opened in 1916, Mum finished her schooling there—though strangely she is not recorded on the first-day roll. My mother always said her father turned the first sod for the Darra Cement Works about 1914—but I think maybe he did the spadework. So my mother’s family were very early members of the Darra community.

The Scotts

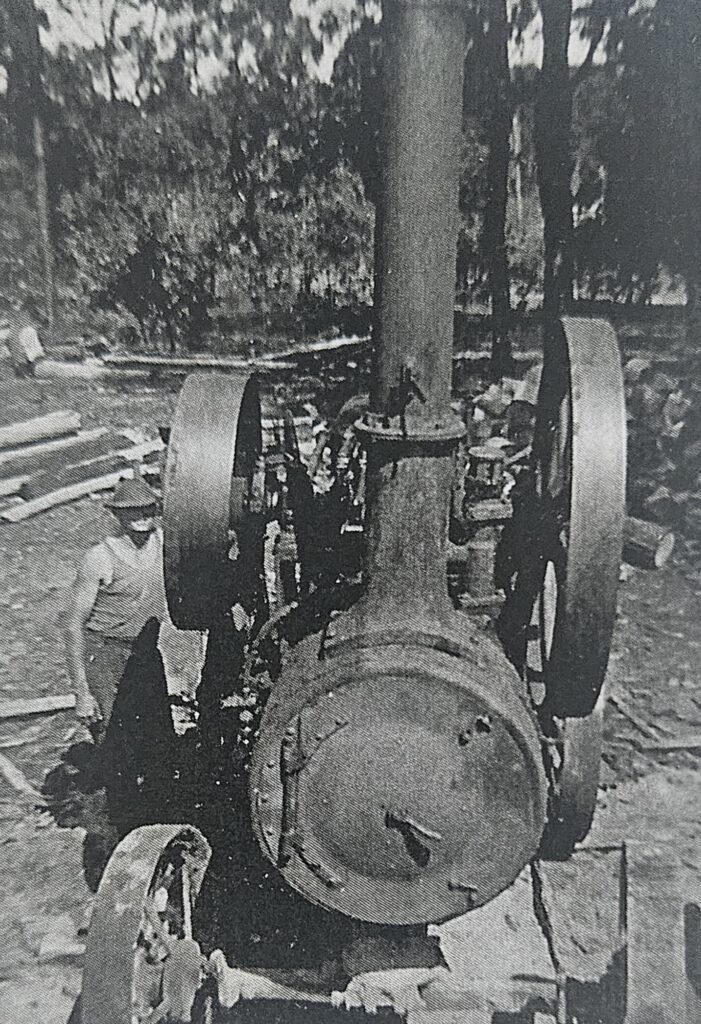

My father was born in Salisbury in 1901. His father was a Presbyterian Scot, and his mother an Irish Catholic: they left the religious differences behind and emigrated in the late 1800s. My father was too young to go to WWI, but his brother Bill did. Bill came back affected by gas and settled in Station Road, Darra. In 1919, my father came to Darra too and set up a sawmill. At first, he had a partner, Bill Bowers, but not for long, I think. Eventually, he owned all of Warrender Street, and every second fellow in Darra seemed to work for my father at some time. The business and the family became quite strong in the community, and I have always assumed that Scotts Road in Darra was renamed for my father.

My parents were married in 1927, at the Yeronga Church of England, and came back to live in Darra. I was born in Warrender Street on 2 October 1932, with a midwife. My sister Shirley was born in 1935. By the time I went to school in 1937, my father had built a new house on the corner of Warrender Street and Station Road, in front of the mill. We went to the Darra School, but I never liked school much. I remember the Darra Junior Red Cross Circle—we had nurses’ uniforms, veil and all. And I remember Richlands people would leave their bikes under our house—and Browns too—when they caught the train to work each morning.

Darra Hall

I remember the school fancy dress balls in Darra Hall. It had a beautiful dance floor, and when they showed pictures they set out the old canvas seats which were stacked at the back of the hall. I know nothing of the Army dances there during the war—we were still children and often unaware of adult things. Years later, in the early 1950s, a Mr. Shay demolished the original Darra Hall and built the Glen Theatre, which was a real picture theatre with a sloping floor.

World War II

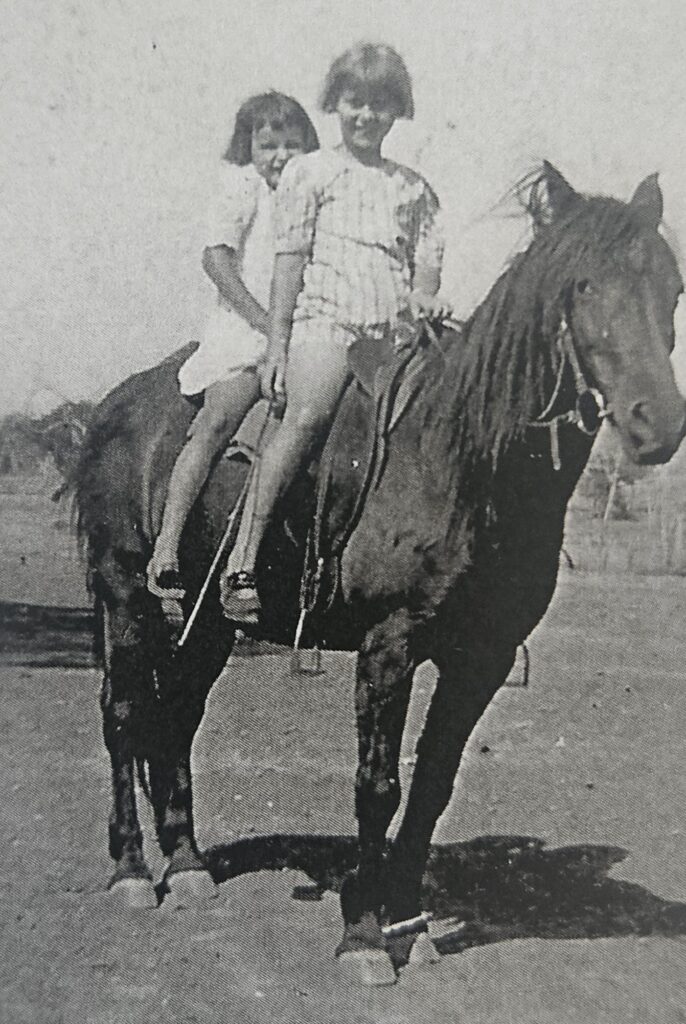

I don’t remember when the war started—I was only seven. But I do remember when we had brown paper over the windows, and Dad’s ute had to have special slit lights—that must have been in 1942. I was ten by then, and the family went down to my uncle’s sheep farm in Texas for a holiday. While we were there, Darwin was bombed, so my parents left my sister and me there for safety. We were there for nine months, two little city girls, with no electricity, washing in the creek with leeches, scrubbing the pinewood floors, and being tormented mercilessly by our sixteen-year-old cousin. We were glad to come home, but found it hard to settle back into school. We had missed so much while down on the farm—though we were supposed to be learning by correspondence, we actually did very little.

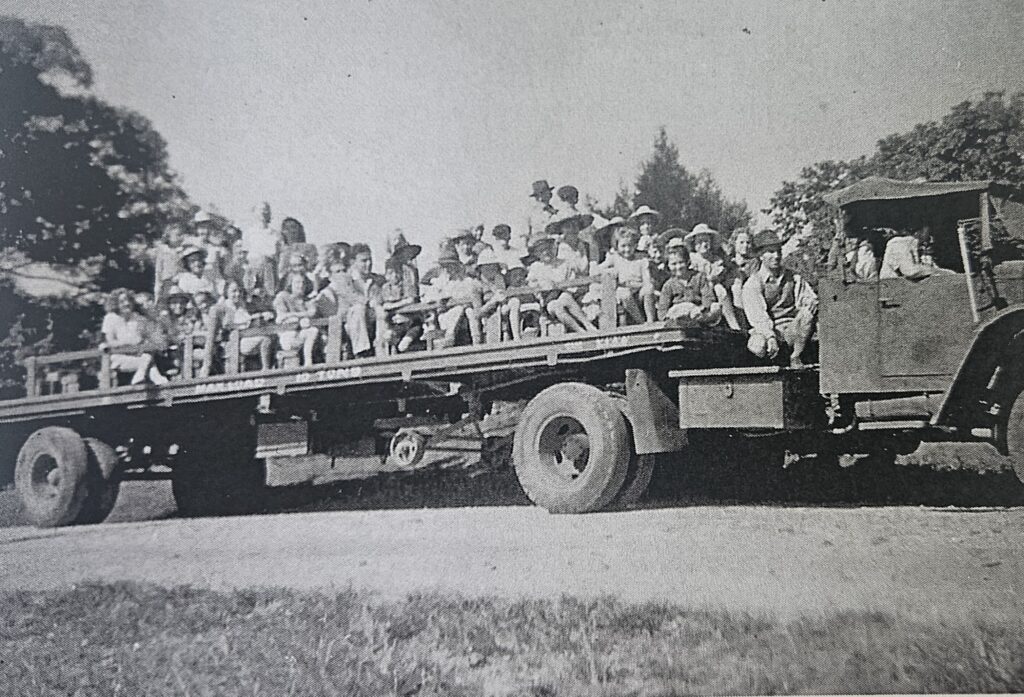

There were lots of soldiers around Darra then—truckloads of colored Americans. They were the first “darkies” we had seen, and we would run and hide from them. But then, I was scared of the swaggies too. Some businesses boomed during the war, but not ours. The sawmill was not considered an essential service, and our trucks were requisitioned for war work. Each night at five, I had to ring Luya-Julius to be told where the trucks were to go the next day, and what they were to carry: often it was munitions. This was the start of my involvement in the family business—I was eleven. Local people were always coming to my father for help—he had trucks and tarps and machinery and gear, and he became involved in many projects, like the Progress Association, Sunday School outings—even the Convent fetes, though we went to the Methodist church.

Darra Ordnance Depot

In 1939, my father had bought 400 acres in Richlands—the high side all along Government Road, in partnership with Fred Weber, Mum’s cousin. They planted pineapples on five acres, and came out at weekends to tend the plants, then sold them in at the Roma Street fruit markets. They were huge, and they sold for two shillings each.

After the war, they built a house at “Pineapples”—from an Army hut left behind by the Americans. Early in 1942, the Military resumed all 400 acres for the US Army but allowed us to work the five acres which we had planted. In fact, our pineapples were growing inside the Darra Ordnance Depot! The US security gate was down at the corner of Archerfield and Government Roads, and throughout the war, Dad and Fred had to have a special permit to come to our land to tend the pineapples. One day they arrived to find several American soldiers in the paddock, among the plants that had not fruited yet. They were pulling them up, looking for the pineapples—apparently hoping they grew underground like potatoes. Obviously, these were real city boys. Another time, they arrived to find a bulldozer digging a great hole in the front of our land. The US soldiers explained that they were “going to take the hill away”—we were on third-grade gravel, and they wanted lots of it for the roads throughout the Darra Ordnance Depot—right next door. My father immediately went into town to convince MacArthur to use the local quarries instead. He never received a penny in rent or compensation for the use of our land—and my husband and I had to fill in the great hole ourselves when Dad sold us the 3½ acres in the 1960s.