I was born in the family home in Wacol, on 14 December 1923. The house was behind my present house at the golf course end of Wuriga Street. (Then the road was called Florence Street—and the suburb was Wolston). My father Fred was born in Wolston too, in 1896, in a slab hut just two doors up. Grandfather James Holland was born in Sussex, England, in 1857. He married Mary Dann in 1882, and in 1884 they came to Brisbane, then Wolston (now Wacol). They and the Olsens were the first families to settle here. About 1886, he and Bill Brittain tried their trade—brick-making—in Wolston. But the local clay had “too much stone.” Bill Brittain moved to Darra and made a fortune (now Boral Bricks); Grandfather tried in Goodna, but met more stone. In 1913, Mother was adopted at age nine, from the Alexandra Home in Coorparoo, by Harry Olsen and his wife Ellen (nee Crookston), whom he had met when working at the Asylum. (Descendants were at first horrified to learn his address: like many staff, he lived in the grounds). Harry Olsen was a gardener at the Asylum; and back then they took 40-50 patients a day into the garden—good therapy, better than they give today, despite all the promotion. My parents were neighbors, and they married here in Wacol in 1923. My name is Keith, but I have been known as Dick since I was a little tacker. I didn’t like to go to the slaughter yards where several of my family worked, and so my uncle called me “Dickie Trout.” And it stuck. I was the eldest—my brothers and sisters were Colin, Jean, Betty, Les, and Ann. I went to school at Darra State School from 1928 to 1937. We caught the train each morning. There were over a hundred kids there, and 12-16 per class. More kids went the other way to Goodna school and convent.

Grandfather Holland was an engine driver—a mechanic really—he ran the steam engine which drove the machinery at the Redbank brickworks. When the brickworks closed about 1932, he moved to tend the only other steam engine left in the area—at a big local bee farm run by HL Jones at Goodna. He sold queen bees. The whole area was covered in bee hives then—there must have been over a thousand around Wacol. And Grandfather was in bees too. Grandfather owned three properties in Wacol. For many years, he was paid to rest and water cattle en route to the Redbank abattoirs. He could water a lot of stock because the waste water runoff from the Wolston Hospital flowed through his land. Steam locomotives also stopped at Wacol station to refill their boilers with this freely available water. “Pumper Greer” ran a steam pump to bring the water up from the waterhole—”the Pumphole”—where it gathered. The mobs, often of 500-800 bullocks, were driven from the saleyards at Cannon Hill across through Inala way, I think. This continued I’d say from about 1900 to 1932, when they built the abattoirs at Cannon Hill. The women went shopping on Thursdays, and if a mob came in, Dad would meet my mother and aunt to tell them that “the bullocks are down.” This meant that they were exhausted and cranky—and dangerous—and to keep the children away from them. Two of the drovers were Goodna men—Darky Harnell and Charlie Hassett (who had been the whip-cracking champion of Australia). They usually came in on Thursday morning, then went on to Redbank the next day. The stock were then yarded for the weekend, ready for slaughter on Monday. In 1932, the Redbank meatworks was closed and we saw no more drovers’ mobs through Wacol. But today there is a huge meatworks at Dinmore, and some cattle are still loaded at the railway siding at Wacol.

The Depression

During the Depression, Father did Relief work, about four days a week. Uncle Tom was cut to one day in six at the meatworks—until it closed in 1932. But Grandfather still worked every day on the steam engine.

There was an old sawmill near Wacol Station, and the “swaggies” would bed down in the sawdust for warmth. They weren’t real swaggies, but to get “The Sustenance” (the dole), the unemployed young men had to move around looking for work. They would beg in the community, knocking on our door, asking for a billy of hot water “and could you put a bit of tea in it?” These were the first men to sign up for WWII—young men in the prime of life, but with no jobs.

Wacol in 1939

At the start of WWII, there was just one shop in Wacol. Mr. Free (the local sanitary contractor) had built a general store and garage near the corner of Ipswich Road and Wacol Road—where the car yard is now. By WWII, I think Percy Hammond was there. There were eleven families living on the river side of the railway, five on the Ipswich Road side, plus five in railway houses. (Six of these were Holland families). There was little employment—the Railway, Wolston Hospital, and Redbank Woollen Mills, which opened in 1937, I think. Uncle Tom continued working for the meatworks when they moved to Cannon Hill in 1932, and Father for the Railways.

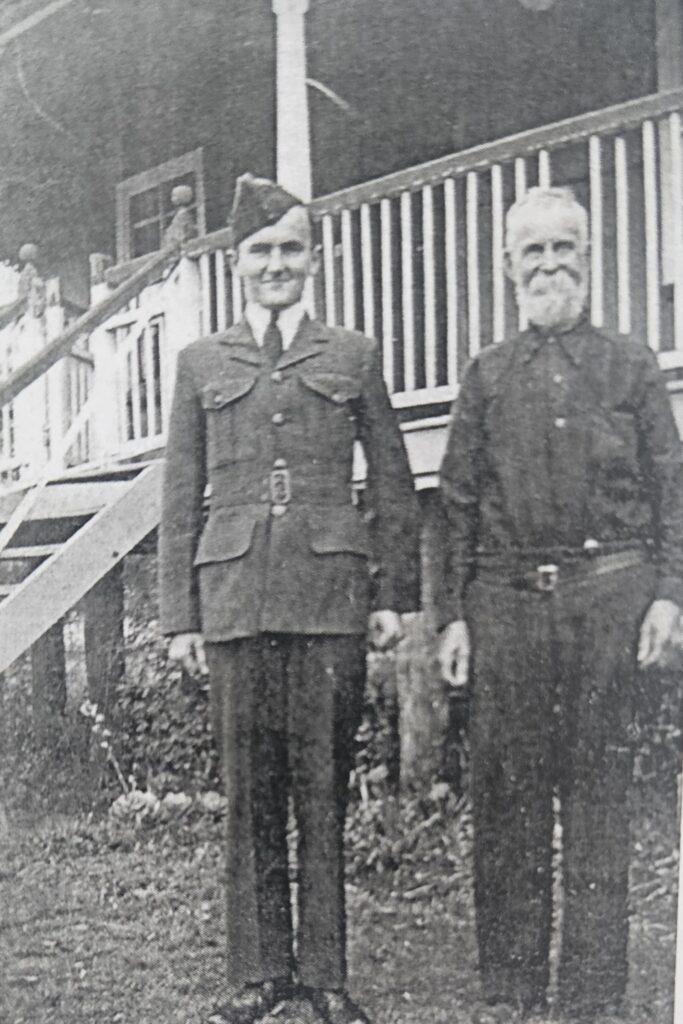

Joining Up

When I left school in 1938, I worked at Morrows Biscuits for twelve months. Then at fifteen, I was apprenticed to an Italian mason at PJ Lowther & Son in Lutwyche Road, where I learned stucco, terrazzo floors, etc.—so I could later build my own house. I enlisted on 11 Feb 1942—in the CMF because I was still eighteen (nineteen was the minimum age for the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), and Grandmother wouldn’t sign to let me go earlier)—and was placed into the 3rd Works and Parks.

I enlisted as a building mason and was sent to North Queensland with the engineers. We were to destroy facilities (bridges, wharves, etc.) to slow the Japanese invasion. Luckily, the Battle of Midway turned the tide, and the war moved north again. Back in Brisbane, I was working at the Albion-Wooloowin railyards with an engineers supply unit, and when there was no building, we helped load trains with materials and equipment. A colored US transport unit from Darra Ordnance Depot brought supplies here, and they would often give me a lift back to Progress Road on their way back to Camp Freeman (Richlands). I got to know a few of these fellows, and they were good men.

I remember one—Albert—was a card. One day he wanted to visit his “little Australian girl” on the way home. He was a little drunk (they often were), and he decided to drive his truck up under the verandah of the place she worked. The verandah came down—and three provosts down the road came up and roared, “What do you think you are doing, you black bastard?” (and worse). “I just swerved to save the life of one of our men—and his little Australian girlfriend!” said Albert. “There they go, round the corner.” Luckily for him, they accepted his story. Another day, the road was flooded when we got to Rocklea. There was an open car with US Air Force officers—done up in their dress uniforms, hats, and shiny badges—at the water’s edge. Albert raced his truck into the water right by them—then braked and reversed quickly “to apologize.” They were soaked twice—and threatened him with a labor gang. Again, he escaped extra punishment. The white officers and provosts were very hard on the Negro men, and I guess these little acts of insubordination showed the men they could win sometimes in the war within the army. When I turned nineteen in mid-1943, I joined the AIF and ended up in the infantry (in the 2nd/1st Pioneers).

Australians and Americans

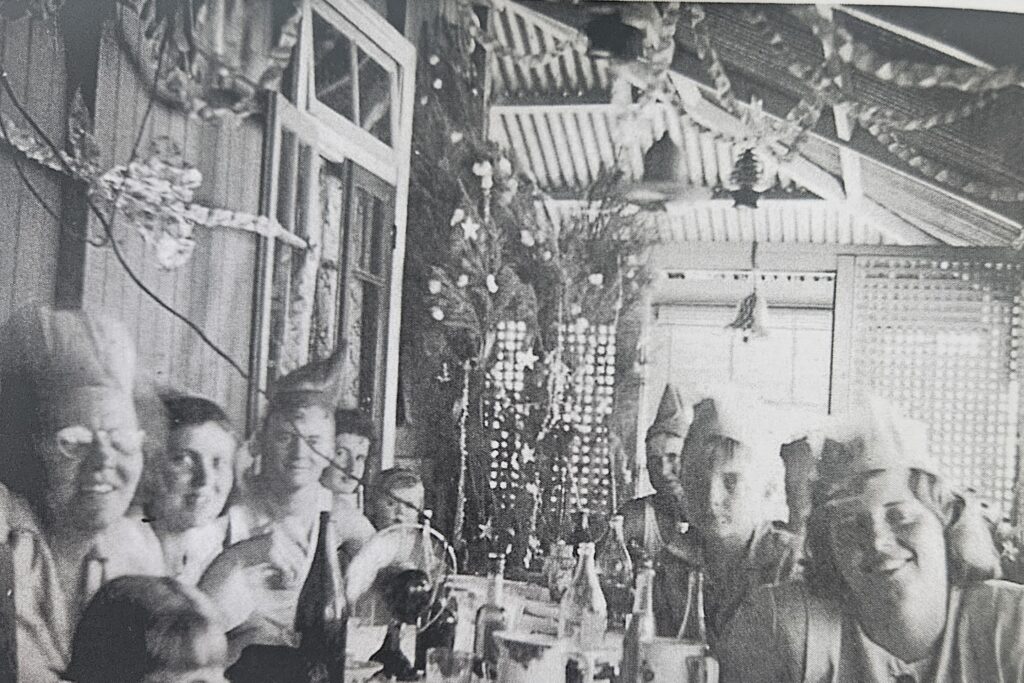

The fighting between the Australians and Americans was terrible: the Australians were aggressive, and the Americans had the pick of the grog and the women. There were even shootings and bayonettings. I later nursed a man in Wacol who had been shot in an Adelaide Street canteen—with a US Tommy-gun—over a beer! His name was Corrie—and I had been in the CMF with his brother. It seemed that all Australians were shipped North asap. About Xmas 1943, they sent five Australian divisions to the Atherton Tablelands—probably to relieve the pressure on the Yanks. I came back to Brisbane only once in three years—a home leave at Xmas 1944 before shipping out to Borneo and Morotai. The American soldiers were friendly to the locals, who were invited to go to the picture shows in Camp Columbia. But there were no facilities in Wacol, so the troops went into Brisbane for their leisure. There were a few girls at Oxley and Goodna who were interested in the Americans—they seemed to love the Negroes, though that was taboo for many of the older generation.

Camp Columbia

This was a staging camp for 5,000 men, plus a 500-bed hospital, and later the HQ of the US 6th Army too. There were thousands of US soldiers and also hundreds of nurses at Camp Columbia. The US hospital was at the corner of Grindle Road and Wacol Station Road. I remember seeing hundreds of wounded soldiers lined up along the road from Wacol station to the hospital—in their red dressing gowns, just sitting, patiently waiting. The building of Camp Columbia was a huge task: the location was really just a huge area of bush outside Brisbane, with no facilities there at all. They had to start from scratch—and they did. The locals told a story that went like this:

The American Colonel shouted: “Where is the nearest goddam water?”

“Darra, Sir.”

“Then it’ll be here in the morning!” (And it was—in canvas pipes along the ground—but it was there!)

“Where is the @#&* electricity?”

“Darra, Sir.”

“It better be here in the morning.”

(And it was—strung along the telegraph poles—but it was there!)

The Americans seemed to have endless equipment, money, and “know-how.” With five thousand men, the Americans needed a good sewerage system. There was a big ablutions block on the hill between Wacol Station Road and a railway bend (on land owned by Burton, I think). No doubt it was sometimes a bit sniffy. After the war, you could see rows of pedestals left on the site. Poo Corner it was called. The US Army commandeered Jim Grindle’s house near the station, and he moved up to Wolston House. Jim used to cart their milk to the hospitals—Brisbane General and the Mater. Thiess Brothers built up their business working for the Americans around here. Herbie Hooth was a much bigger contractor than Theiss at that time. But his quote for Progress Road was way under, and he lost his business, his house, everything! Maybe the alcohol helped too. For locals, it was good to get a job with the Americans because they paid better. Australians earned each week roughly what American soldiers earned in a day. I got 7/6 a day because of my trade (unskilled infantry got 6/-). I remember Jack Sardis, an Italian mason, was paid good money working for the Americans. But he had to hide at times when the Australian authorities were on the prowl for “aliens” to intern.

The Railways

At Wacol, where much of the munitions from Darra Ordnance Depot were loaded to go north, you could walk from the railway to the highway without touching the ground—on thousands of bombs lined up out in the open. My father worked for the Railways, and he said that most weeks ninety goods trains left Roma Street Station taking men and munitions north. He started as a weighman for the coal trains at Wacol, but shift work didn’t suit his family life, so he ended up on a crane at Roma Street. My brother Col joined the Railways at age fifteen, and became a train driver. Throughout the war, he brought coal trains through Wacol. The locals hated the coal-weighing facilities. Each railway truck had to be weighed individually—and all that time the gates on Wacol Station Road were closed. It was very inconvenient. My uncle Bill Holland’s house was moved to make way for an overpass for Wacol Station Road. That was in 1949, but the overpass never eventuated, so he continued to live there until he died; then the house was let out for years. In 2005, it still sits in the Car Yard on Ipswich Road.

American soldiers would throw sweets out of the troop trains—with their name and unit, hoping someone would write to them. This happened in the country towns, my wife says. Australian soldiers were more likely to hand out blown-up condoms to the girls.

The American Provosts

There were no soldiers wandering around Wacol—the Americans were very disciplined. Their provosts were armed with Thompson sub-machine guns—and they weren’t afraid to use them, by jingo! They shot several soldiers who reportedly raped local girls. Those shot were all Negroes—though they were no worse than other men. The Negroes, who were mostly a good style of men, suffered at the hands of the big white provosts. Bill Watson, a night officer at Wacol station, told me what he saw one day. A Negro who got off the train at Wacol was attacked by white soldiers, called a “black bastard,” and pushed onto the railway line. He came back up onto the platform with his knife drawn (all Americans seemed to carry knives) and stabbed a white American as he opened the gate. Bill rang the hospital—but they sent the provosts. The provosts hunted down the Negro—and brought him back shot to pieces. Mrs. Owens, wife of a burner at the brickyards, said she found a Negro soldier hiding on their veranda. “I mean you no harm, Ma’am, but the provosts will kill me for something I didn’t do.” She could see them, banging another poor man’s head into the rail line. She let him stay hidden, and he did no harm. She always wondered what happened to him. I heard they shot another man at Darra, near the RSL Hall. He ran into the thick lantana to hide—but they used their machine guns.

The End of the War

The Australian 6th, 7th, and 9th divisions were on the Atherton Tablelands for eighteen months, marching around with nothing to do! When the US set off to retake the islands, MacArthur refused to take us and apparently said we should “go home and make uniforms and grow food.” He planned to send the 7th to Cambodia to get us out of the way. We could probably have helped at Okinawa. Instead, we were sent into Balikpapan. I was in Borneo when the war ended—and we had to wait there until the Americans got their men home first. I left the islands in April 1946, and I was demobbed from Redbank soon after. By the time I got back to Wacol, the military had gone, and the first “displaced persons” from Europe were being housed in Camp Columbia—mostly Polish and Dutch people who had lost everything in the war.