This story is written by Maria Douwes and published in her book: Back to Australia

The Douwes family was one of the last families to move from Amsterdam to Australia for a hundred guilders. Both the Australian and Dutch governments sponsored this trip. On December 9, 1960, Maria Douwes emigrated to Australia with her parents, five brothers and four sisters. They sailed via the Azores to Curaçao, through the Panama Canal to Tahiti and via New Zealand to Sydney. The story of their trip on the Zuiderkruis is available here.

The were registered at the Wacol Migration Camp in Brisbane where they arrived in January 1961. The part of Maria’s story at Wacol is told here.

Now the story continues here about her early life as a Dutch migrant in an Australian community.

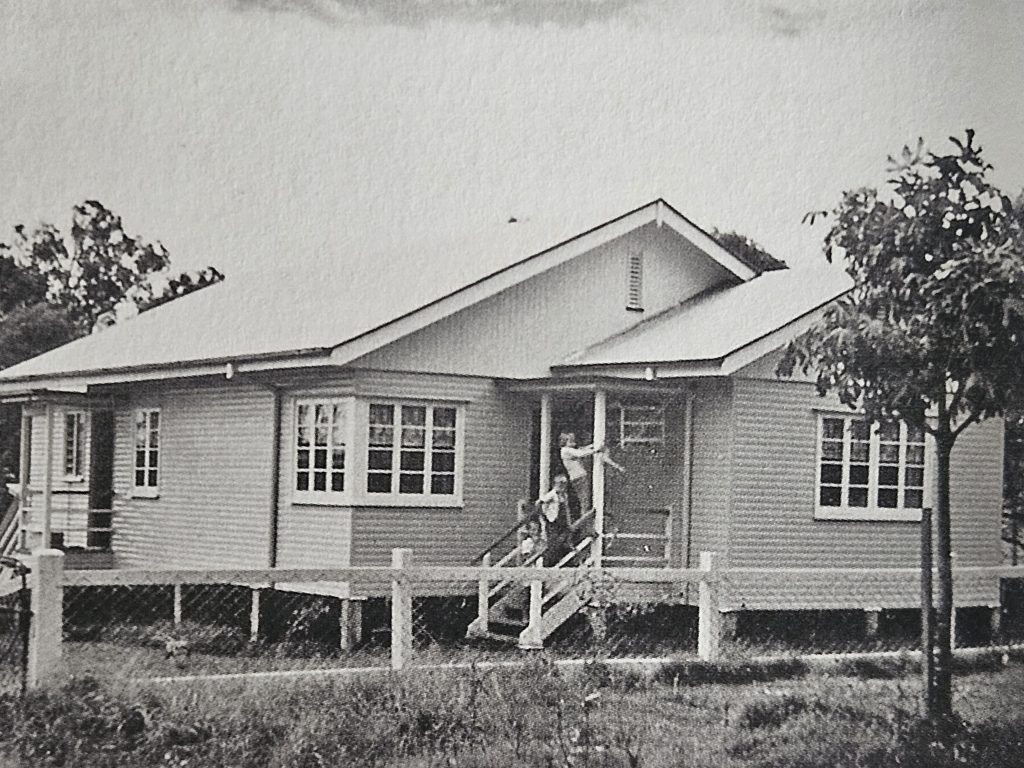

After seven month in Camp Columbia they got a house at Poinciana Street 54, Inala. A lot of Dutch people and immigrants from r European countries live here. It’s a suburb of Brisbane, where the Queensland Housing Commission started building houses in the early fifties. It was built in the middle of the bush. That’s why, just before you move into a house, it has to be disinfected. It is built on poles, against and snakes.

Richlands State School

Richlands, where our school is, borders Inala and was only a five-minute walk from our house. The school was surrounded by orchards and vineyards. Each holiday we would go and get fruit at the Justice of the Peace who lived on Archerfield Road and had grapes amid tangerines. You could pick as many as you could carry and some more for the road. We drive through Magnolia Street to Progress Road and turn right auto Orchard Road. Here is the main entrance of the Richland State School.

The school buildings are lined around the school parade ground. Seven hundred children are lined up, some of them in their green school uniforms with a white hat on. Most of them in plain clothes though, on bear feet. Not all of the parents of these children can afford to buy shoes. We are on parade and Mr McCasker keeps his daily speech. He thunders through the microphone that we have to be obedient, that we have to pay attention in class and he warns us what will happen if you don’t listen. He tells us he had to punish three boys again yesterday because they hadn’t learned their lesson. His head is getting red and he looks pretty threatening.

We are glad when he’s done and we hear the melody of ‘God Save the Queen’. We sing along at the top of our voices, relieved. After the singing we all promise in one voice: “to love God, honour the queen, serve our country and play the game.“

Hans, Jos, Agnes, Chris, Simon and I, all get up at six in the morning and are at school by six thirty. It’s much too warm to stay in bed. From seven o’clock you can pick up sports gear and then you can start playing on the large sport fields around the school. Later in the day, it is too hot. We usually play soft ball. With six you can easily play it. We have a good bat, a soft ball and a few beautiful leather gloves. We didn’t have all that in Holland. At eight we have to be on parade. We are with our own class in rows behind each other, standing up straight, your arms straight down against your body, like little military kids. As soon as Mr McCasker has finished his thunder speech, and the singing of God Save the Queen is over, the military marching music sounds through the loudspeakers and we march to our classes. Our teacher, Mr Parker has a roaring voice and calls out: “Lep, lep, lep, right, lep.’ Instead of “left, left, left, right, left. “He was a sergeant in the army. As soon as we enter the classroom, we have to stand up straight next to our desks. We recite a poem.

Where the Pelicans builds by Mary Hannay Foott

The horses were ready, the rails were down,

But the riders lingered still. One had a parting word to say,

And one had a pipe to fill.

Then they mounted, one with a granted prayer,

And one with a grief unguessed.

“We are going,” they said as they rode away,

“Where the pelican builds its nest!”

Every month we learn another poem, A song of Cape Leeuwin by Ernest Favenc, Seafever by John Masefield, Daybreak by Henry Longfellow. We also learn the tactics of meeting and debating effectively. Mr Parker establishes the school choir and he coaches us fanatically with sports. With his roaring voice he drills us as if his life depends on it. He is strict but fair and he hardly ever hits anyone.

Inala High

There was the central square, surrounded by the school buildings where we assembled each morning to raise the flag and sing the national anthem. Our principal was very progressive and one morning he announced to abolish the hitting at school. Everyone was happy. After a couple of weeks, he told us that it appeared impossible not to hit anyone. The pupils remained disobedient they didn’t learn their lessons and didn’t take the rules seriously. So, he had to start beating us again, as we would certainly understand.

Our pride of our school, our country and the queen were drilled into us. Every day you had to appear on parade in your full uniform, which was a blue pleated skirt and a checked blouse, for girls and a school tie had to be done in the right manner with a school pin on it. Then you had a hat for the summer and a blue beret for the winter. And of course, we had to wear shoes. If you were not in complete uniform at the inspection you would be sent off parade. Naturally we had our own school song

We’re the students of Inala High Onward we drive

Upward we strive To our country, home and school we’re true

And we hail our colours white and blue

When we are asked to give our best

We pass each test, excel the rest

And from our hearts will never die

Fond mem’ries of Inala High

Yes, we’re proud of our Inala High

When questioned why

Here’s our reply In our quest for skills and learned ways

Of our school’s great part we sing full praise

And when our life at High School ends,

We pack our books, farewell our friends

And never to the world deny

Our love and thanks, Inala High

Every morning some children would faint in the burning sun. In 1964 when I was going to school here with Marina, ten girls of thirteen years old, became pregnant. They were seduced in the bush around the sport fields, by boys from the highest classes. The girls were expelled from school and never heard of again. The boys remained anonymous. After that we were only allowed to play sport separately and the boys were not allowed on the girls’ sport fields and the other way around. Months afterwards there was still whispering going on.

When we came from school, we immediately took our socks and shoes off and took off our tie. Continuing nicely on bare feet. My feet were usually swollen and the inside was bleeding because after three years with no shoes on, I kicked the inside of my feet with my shoes. You just had to take care not to bump into a prefect because he would order you to put your socks and shoes on straight away. If you were not in your complete uniform after school you would be a disgrace to your school. So, we walked to the bush as fast as we could, where usually you wouldn’t bump into anybody from Inala High.

February 1962

Mister Carrol writes the words of Waltzing Mathilda on the black board and explains to us what they all mean. There are a lot `slang’ Australian words in it, that other English-speaking people don’t understand at all. Do we know what `sheila’ means? That’s girl and fair dinkum’ means ‘really, honestly’ and ‘tucker’ means food. Well, we do know these words. But the song? Mister Carrol explains and after that we sing the song Waltzing Mathilda.

March 1962

Hans jumped a fence during our break and Mr McCasker witnessed that. He had to come to his office and you knew what you could expect: the cane. You had to hold out your hand and then McCasker would hit you so hard, that you would see red welts on your hands. Sometimes the injuries were so bad, they had to be treated by a doctor. Now and then you heard something from a boy who had been sent to him. Hans refused to hold his hand out and he could choose: the cane or get sent home. He went home. Of course, he told us all the details at dinner. He was rather tall and was showing his smaller brothers how easy it was to jump the school fence. That was not permitted. How could he have known that? My parents didn’t understand all the fuss about it either. The next day Hans went to school as usual, as if nothing happened. McCasker came to have a look in his class to see if perhaps he had been beaten black and blue at home, what happened in many cases. But, naturally, not in his.

One of my younger brothers, Chris, was expelled from the Richlands State School. He was a special case. If he was beaten, he attacked the teacher, threw the chairs or school desks through the classroom or bit the teacher in his arms or legs. In short, his fuses went wild. I always had great admiration for him because he dared to revolt. After umpteen attempts to hit him and the tantrum that ensued, he was expelled and the school inspectors got involved. Chris was not allowed to go to any school in the whole state of Queensland unless he submitted to corporal punishment. My parents were notified of this decision by an official letter that they had to instruct their son likewise. They refused. Finally, after a few months at home, Inala State School took him in and promised they wouldn’t hit him.

November 1962: Guy Fawkes Day

Haseman family, owner of the chicken farm where Hans, one of my older brothers works, invited us to come and celebrate Guy Fawkes Day with them. This morning at school, Mr. Parker told us today we commemorate a military man who tried to set fire to the House of Lords with fuses and fireworks in 1605, with the intention to depose the Protestant king Jacob I. He was caught in action and sentenced to death.

We light a straw doll, light fireworks which don’t really belong to celebration, and the boys, Mark Haseman and my brothers Hans and Joseph, go hunting for rats in the chicken barns and feeding sheds. I stay at the fire, talking to Paula Haseman and her mother who asks if we would like a drink and invites us into the house. It looks like a movie scene to me: beautiful, shining furniture and everything so nicely in its place. Nothing is lying around and everything is clean. Sometimes you see such pictures in magazines or on television.

April 1962

Jos and I are allowed to go into town by ourselves. Jos fell and broke off a small piece of one of his front teeth. We take the bus at the back of our house in Lilac Street to go to Darra where we take the train to Brunswick Street Station in Brisbane. You have to clean the seats in the train with a handkerchief because they are black with soot. Most of the trains still have steam engines here. I like them. There’s a whole row of doors in a wagon with long benches. You can get in and out from both sides. We take the slow train. Before we come to Brisbane we stop at a lot of stations: Oxley, Corinda, Sherwood, Graceville, Chelmer, Indooroopilly, Taringa, Toowong, Auchenflower, Milton and then Brunswick Street. It takes about an hour. We walk to the end of the street and turn right, to report to Simone, our second oldest sister, who works at McWhirters. She shows us how to walk to the Dental Hospital. We follow her instructions and we see the huge letters: Brisbane Dental Hospital, a beautiful building with a high staircase and pillars. Jos doesn’t have to wait long and before we know it, he walks out with a nice piece of white gold on his front tooth. He feels proud. He is worth more with this piece of gold now. We walk on to the General Hospital, where I have to get my eyes checked. It’s not far from the Dental Hospital. I might need a new pair of glasses. I don’t have to wait long either. My eyes are still the same and I can keep the glasses I have. That’s good! When our appointments are over, we have a whole afternoon to do what we like. We go to the Natural Museum which is at walking distance from the General Hospital. This gorgeous building, on the corner of Gregory Terrace and the Bowen Bridge Road has an enormous attraction for us. We see stuffed animals and dinosaur skeletons. We don’t know where to look first. Jos and I have never been in a museum in The Netherlands and we are short of time. When it closes at five, we have to rush back to Simone. We’ll take the train back to Darra with her.

January 1962

When it is too hot to play outside, we watch television. We have three channels and most of the programmes are American series. We love watching Rin, Tin, Tin, the Mickey Mouse Club, Roy Rogers, Ivanhoe and many more. When it’s cooler, we go outside. Joseph, Chris and Simon are the cowboys who are attacked by the Indians, our friends, and I’m Annie Oakley who can shoot faster than the boys. Stagecoaches, gun pop, Indian screams, we are totally into the game. At school we learn that in the old days the stagecoaches of Cobb & Co drove through the entire land of Australia. Even in Inala where we live. We learn ‘The ballad of Cobb & Co’:

There’s a hustle and a bustle in the old hotel tonight

The bar is over-bursting and the lights are gaining bright

They’re waiting for the horses who have been through the night

And they’re waiting for the coach of Cobb & Co Cobb & Co,

Cobb & Co And they’re waiting for the coach of Cobb & Co

There’s Billy Jones the jackeroo still breathless from his ride

He bought a brand-new sulky and he’s standin’just outside

He’s waiting for the pretty girl who’s gonna be his bride

And she’s coming on the coach of Cobb & Co Cobb & Co,

Cobb & Co And she’s coming on the coach of Cobb & Co

June, 1963

At school today we received a round chart of the starry sky which you can turn to this time of year. Marina and I go outside to look if we can find the stars we see on our charts. The sky is almost black with millions of small lights, the Milky Way. The Southern Cross, also called the Crux, is the smallest Zodiac sign in the sky, Mr. Parker said this morning. In the past it was part of the Zodiac sign Centaurus. We can see that easily. Australia, but also Brazil, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, the Coconut Islands and Samoa all have the Southern Cross in their national flags. “Look”, says Marina, “there’s Aquarius and Capricorn.” Now in turns we see other Zodiac signs on our chart: Scorpio and Orion. “These zodiac signs you only see in the southern hemisphere,” says Mr. Parker. Marina and I feel very lucky that we live here.

August, 1963

Marina and I are going to Brisbane. I told my mother Marina could go and she told her mother I was allowed to go. It worked. The exhibition is once a year and there’s such a lot to be seen. There’s a fair, a rodeo, all sorts of animals, parades, judging competitions and lotteries. In Brisbane it’s the event of the year. Everybody talks about it and people from all over the state come here. Its the largest event in Queensland. In The Netherlands we call it a year market. It is not far to walk from Brunswick Street Station to the Exhibition Grounds. We’re very excited. We are wearing our Sunday dresses because it is a real feast! As soon as we step through the porch, we see the Ferris wheel. We don’t dare to get in. There are merry-go-rounds, shooting tents, you can buy lottery tickets and win nice prizes, and you can buy large pink cotton candies and a large bag of popcorn of a metre long! We take one of those so we have something to eat on the way. We keep a close eye on each other because it is so busy you can easily lose track of each other. First, we take a good look all around. There is so much to see. The rodeo has just started. Nobody really lasts very long on such a wild bull. It’s quite a laugh when you see how easily the boys are thrown off. If you’re good at it, you can win some very neat prizes such as a television.

Everywhere you see animals within fences. It really smells awful. Here they are judging the merino sheep. “They have the best wool in the whole world,” Mr Parker says. A little further we see all sorts of cows and still further lots of horses. I wouldn’t mind having my own horse. I would go galloping through the bush. Not such a high one as you can see here, but a small one, a brumby, a wild horse that we sometimes see in the bush.

One of the large halls on the exhibition grounds is full of cages for chickens, geese and ducks. I like the chicks a lot and you’re allowed to hold them. But we have that at home, so it’s not such a big deal for me. For Marina neither. Then we see a lumberjack exhibition. Whoever is the first to cut a long tree trunk wins a prize. It takes too long so we move on. Here the motorbike competition has just ended and you see the boys taking off their helmets and brush off the sand. Their heads are red and sweaty. They look pretty tough though. Next are the mounted police who catch our eyes. These policemen on horses look mighty fine in their beautiful uniforms and with flags. I have never seen so many different kinds of people together in my life.

November 1963

Mr. Parker has a new poem for us today. We will be going to Highschool soon and he thinks the students of the seventh grade should know the poem of Ernest Fevenc. It is about the discoverers, the Dutch, who were the first to visit the unknown south land that was known as ‘terra australis incognita’. Almost a century before the English came. This poem is about the most southern point the west coast of Australia, Cape Leeuwin, which is a lioness Dutch. The lighthouse speaks: The Song of Cape Leeuwin by Ernest Favenc.

November 1963

Its Saturday afternoon, November 22nd, 1963. Paul de Kruyf comes running into our street, jumps the fence into our yard and screams: “President Kennedy has been murdered!” We sort of laugh a bit and tell him he should not make jokes like that. “See for yourself if you don’t believe me. Turn the television on!” When we try to calm him down and make a joke about it, he starts screaming louder: “Turn the television on, then you’ll see!” And to our bewilderment it’s true. What a terrible shock. We can hardly believe what we see and hear. Holding our breath, we are glued to the tube and we see the replay, of how president Kennedy falls in his car and how Jackie tries crawling away at the back of the car, many, many times. It’s just hell and we’re all fighting our tears. The first comments from eye-witnesses point to a building where the shots came from.

November 1963

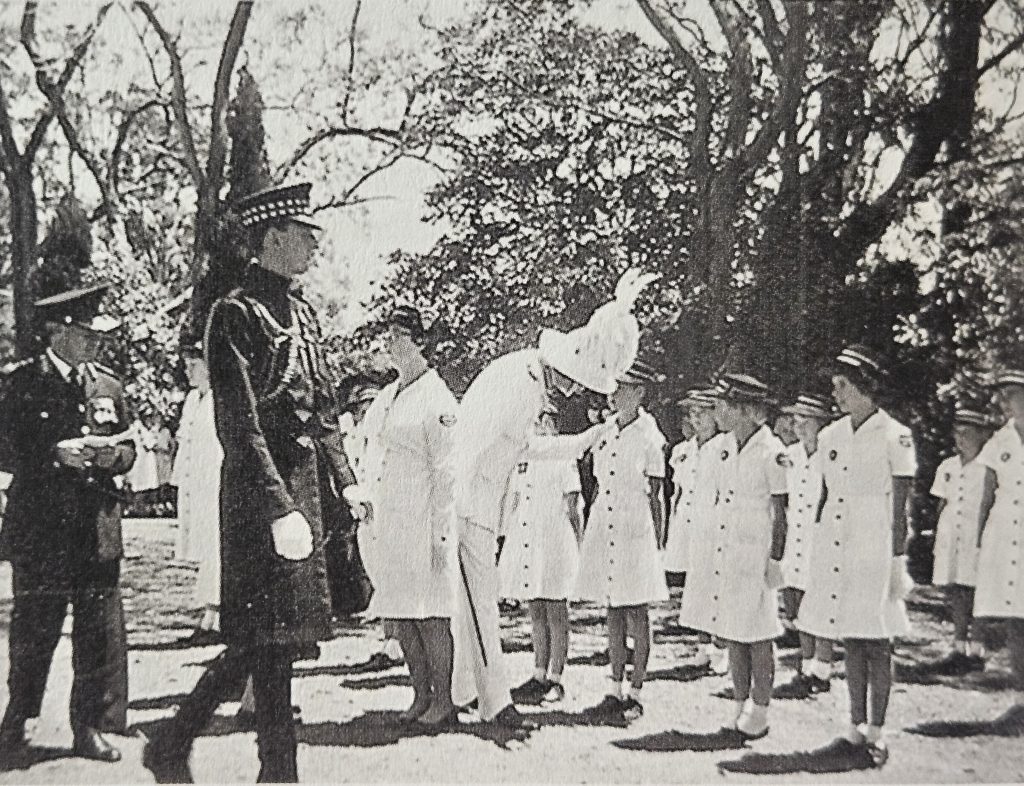

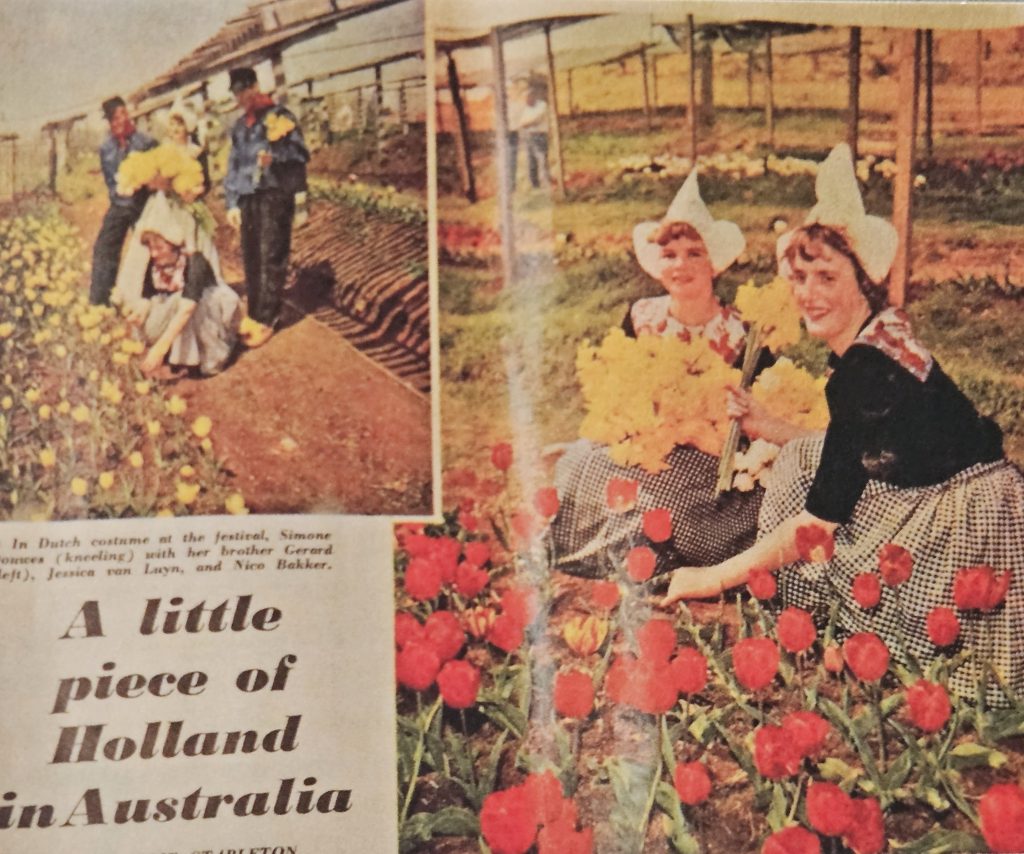

Marina and I are allowed to go on a bus trip for Dutch women. We have an outing now and then because we are members of the Saint John’s Ambulance Brigade. On Sundays we often stand along the lines at a rugby match and we’ve visited the governor of Queensland with a delegation once. We have our diplomas for First Aid and Nursing already so, if something happens, we know what to do. On the morning of our trip, I am sick as a dog, which happens more often when we go away for a day. “It’s all excitement,” my mother says. She is coming along too. We’re going to the ‘Spring Brook Tulip Farm’ in the mountains. Marina and I are wearing our uniforms and hat and go and sit in the back of the bus. It’s about a two-hour drive and soon all the women are talking to one and other. We drive along the coast for quite a while and pass Surfers Paradise, Brood Beach, Mermaid Beach and Miami. Near Tweed Heads, we turn right, towards the inland. Then we come into a totally green area.

Beautiful forests, sometimes a waterfall. When we arrive at the tulip farm of the Van ‘t Hof family, I see my sister Simone standing there and my brother Gerard. They are wearing Volendammer costumes and they will be folk dancing in a while. Everything is blooming here and it smells really sweet. When we drive back at the end of the afternoon, we halt at a filling station, and Marina and I go inside to have a pee. We get some photos of The Beatles and when we ask some more, for the whole bus, we get a whole pile of them. The mothers are begging us for some for their children and now we feel our power. We say, “Then first, you’ll all have to sing some Beatles songs.” And the whole bus joins in with: Love, love me do, I want to hold your hand, She loves you, Twist and shout, the whole repertoire comes by and again and again one of the mothers starts singing another song. Marina and I divide the photos of the Beatles equally and our day is made. We didn’t know that mothers also liked The Beatles. They never told us.

December 1963

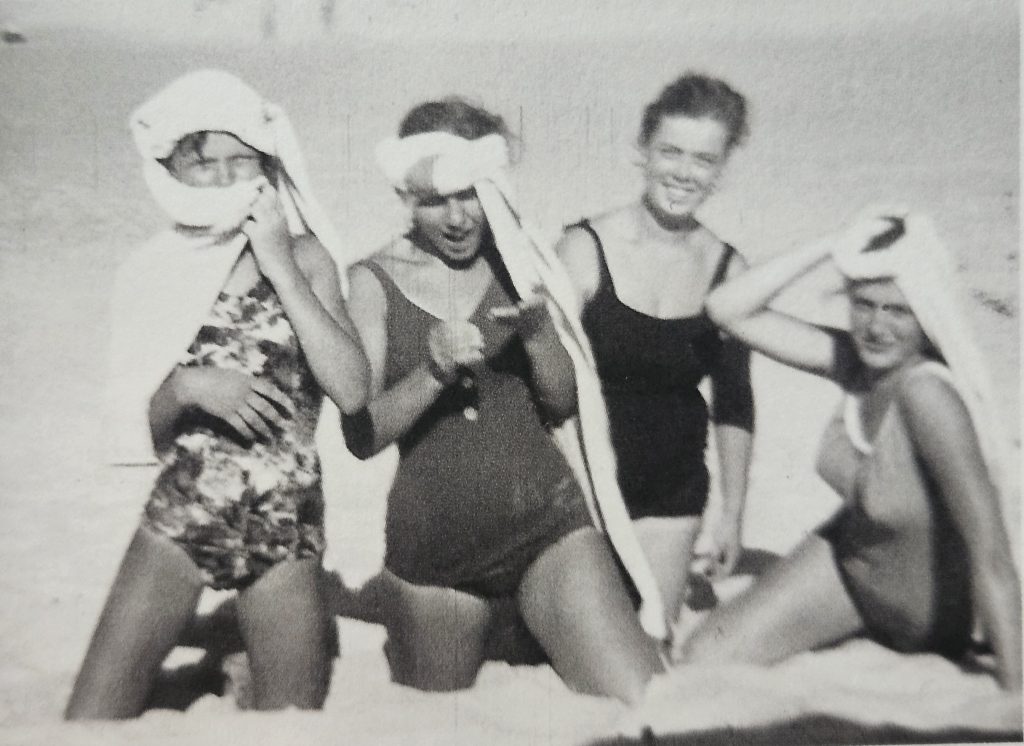

Bob, one of my father’s colleagues, comes by on Sunday and asks Simone might want to come with him to the beach. It’s high summer and we are all puffing and sweating. “Let’s all go together,” my father says. Bob is speechless but we kids are yelling and start running around the house, looking for our bathing suits and after an hour or so, we are ready to go. We have been out with Bob before, to a rodeo, where he was a real cowboy. He has a large pick-up so we all fit in the back easily. My mum and dad sit in front next to Bob. We have so much fun because we don’t often get a chance to go somewhere. We don’t have a car ourselves so with all of us, it almost never happens. Sometimes I go to Saint Lucia College with Ineke, on the back of her scooter, where she works in the kitchen. Then I may help her in the kitchen. That’s also a kind of outing. But this…! We, the four big sisters make turbans for on our heads, the boys are in the water continuously and we dive in now and then. The waves here are so strong that if you don’t watch out, they hit you so hard that you fall flat in the water and you go under. There’s also a very strong current. On high, tall stools the lifesavers are looking for sharks. When they spot one, they get their megaphone and call out ‘Sharks!” Then everybody runs out of the water. We find it all very exciting and amusing. Bob is a bit grumpy so we don’t pay any attention to him.

December 1963

I’m lying in a dark room, am not allowed to read, to watch television and must stay flat on my back. What I can remember this: we we walking back from the swimming pool, where we sat in the burning hot sun the whole day. I had hardly been in the water. I didn’t feed well while walking back. It was my turn to carry the heavy bag with wet towels and swimming gear. I was dizzy and seeing black spots. I did say I didn’t feel well, but I was snubbed with: “You just don’t want to carry the bag.” When I got home, everything turned black I was lying in an ambulance and was dying of thirst. I tried to ask for water but only some strange sounds came from my mouth. At the hospital they tried to make me drink some sort of medicine but I wanted water first. They kept telling me it was good for me but I was so thirsty that I didn’t want to finish that dirty drink Then they took a hold of me and forced the drink down my throat. I kept being thirsty but they didn’t think of giving me some water I felt so hopeless because I couldn’t speak.

I had a sunstroke, my mother told me. And for the time being I had to stay in the dark, inside. Derek Graham came to visit me. Well, he stayed outside because he didn’t dare to enter my room. He had a bag of plums with him, that he got at school, for me. That was really sweet of him, I thought. I got many more plums from friends. At last, I ate so many that it upset my stomach and I spent a long time in the bathroom.

When we needed fruit, we went to pick it ourselves: strawberries, mandarins, oranges, grapes and plums. Everything, ripened in the sun, very sweet and juicy! You paid next to nothing and for on the road, you would get as much as you could carry, for free. For us fruit was a substitute for sweets.

January 1964 – De Kruijf Family

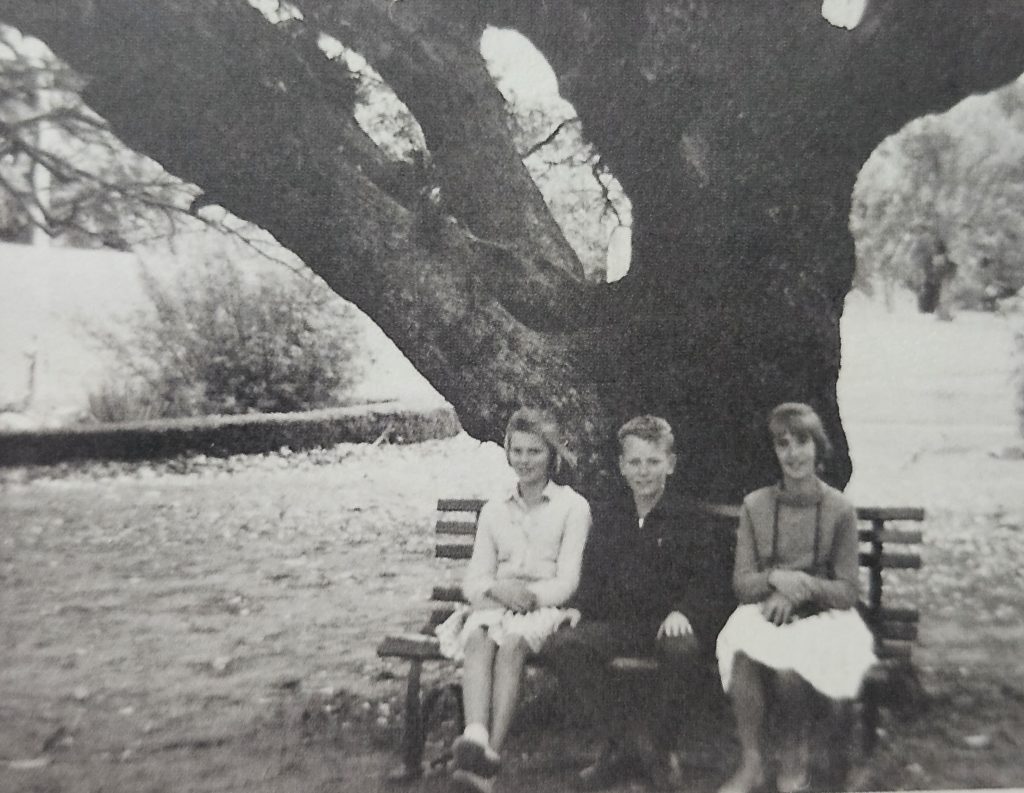

Paul has been living at Old Clem’s for years. We often walk over there on a Sunday afternoon with some family and friends and on our way, we often see wild horses. Hans and Joseph take a rope and try to catch one but I find them a little bit too wild to come closer. We walk into the bush at the end of the Archerfield Road. Here it’s just slightly higher than the surroundings, so you can look very far. In the distance you see mountains and closer by the grape vines of the farmers in this area. We pass the house of an Australian, which looks more like a shack than a house. A bit further we see the house of a Dutchman, that looks more like a villa. They have done very well in this country. After about an hour through the bush, we reach Old Clem’s. Old Clem’s is built on high stilts, so the stagecoaches can park underneath. There’s no running water here and no electricity. The De Kruyf family uses kerosine lamps, a kerosine fridge and even a kerosine iron. When Paul’s mother has time, we can have a look inside.

She shows us the stove that she heats with wood. The water tank is next to the house and catches the rain water. If it hasn’t rained for a long time, Paul comes to have a shower at our place. Old Clem’s is magical. We find it very exciting. Everything is different here than at our house. The centuries old mango trees have a special effect on you.

January 1964

Our five boys sleep in one room all together. Two bunk beds and one single bed. Simon, my youngest brother, sleeps in the single bed and has a chamber pot under his bed for when he has to pee in the middle of the night and there’s also a burning mosquito coil to keep these pests away. The mosquito coil is too close to the bed which makes the matrass catch fire. The room is full of smoke which wakes my oldest brother Gerard, who panics and throws the full piss pot over the bed. It works. The matrass goes out and is thrown into the garden. Everyone is awake. We all laugh and talk about what might have happened, and that luckily the pot was so full. We all go back to bed. After a shower and clean pyjamas Simon continues his sleep, on an improvised bed from a few blankets, on the floor.

April 1964 – The Theunissen family

The Theunissen family suddenly comes to visit. They’re totally broke and have hardly had anything to eat lately. They are thin and look messy. They were our neighbours in Camp Wacol and Jan worked in the coal mines at Mount Isa after that. He told us it was so hot there, that you could hardly breathe. But the money was good. After that he took his family to Cairns for the sugarcane harvest between June and December.

Mr Theunissen says there were so many casual workers in Cairns that he could only work now and then. He tells us that at the sugar-cane fields they first burn a whole field to dislodge pests and snakes and then you stand bent over all day long in the burning sun to cut the sugarcane loose with a machete. They have very sharp stems which can make deep cuts in your hands. His hands show all sorts of scars and cuts.

Agnes and I have to leave our room so Mr and Mrs Theunissen can have a few good nights’ sleep in our comfortable double bed and we can sleep in their van with their kids. We lie talking every night until the early hours. They have seen a lot more of Australia and life than we have. Jantje tells us one night that sometimes they ate from trash cans because they had nothing to eat. Only the idea of it makes me sick and I feel very sorry for them. At the table Mrs Theunissen snarls at her little boy: “Stop your bullshit and stuff your food.” We all fall quiet because we’re not used to such language and reproach. After a couple of days, the family is on their way again.