I have lived in Forest Lake for years. But during World War 11,-I was in Java. When the Japanese invaded, the Dutch East Indies government escaped to Australia and ended up at Wacol. My family came later, in 1945.

Dutch East Indies

My grandfather was Polish, and he met and married my grandmother, who was Javanese/Dutch, in Surabaya. He added “de” to his name, which made it sound Dutch. So my mother was born in Surabaya in 1900 and grew up in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia)

My father was a Scotsman who came to Java when he was a teenager. His parents had died, and he came out with some other young men. He met my mother when both worked at the Singer Sewing Machine Factory in Batavia. They married in 1920, and then went to South Africa to join my uncle who lived in Durban. My grandmother followed her daughter.

I was born in Durban, South Africa, in 1921, the first child in my family. My father worked there for a time, though we were never registered. But it wasn’t what my parents expected, and we returned to Java when I was two or three. My three sisters and two brothers were all born in Surabaya.

So I grew up in Surabaya, educated by the Ursuline nuns in a convent school and my mother and I were very close. In 1942 I was twenty-one and worked in a Dutch bank.

Invasion

And in 1942, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies! That they were coming was known: we were paid off at work and told that we would all have to look after ourselves. No doubt a few people left the country, but for most, this was the only country we knew.

The Japanese took the houses they needed for their officers. At first, a payment allowed a family to stay in their home. We all paid. But within two months, they took all the big houses anyway. One morning three or four soldiers came into our house, sat down and put their feet up on the table. “This is ours now” they said. Our dog barked — and they shot him!

They interned the British first, then gradually all the Europeans. Our whole street was given a couple of days to be ready — and we were only to take what clothes we could carry.

In the Camps

Our family was separated. Mothers and daughters were kept together in the camps — with boys up to age twelve. Fathers and sons over twelve were put into separate camp. My younger brother came with us at first, but when he turned twelve, he was taken to a camp in the country, and only later sent to the men’s camp with my father.

At first, we were mostly Dutch in our camp, but as more were interned there was a great mix of nationalities in together. It was amazing how quickly the children learned to understand and communicate in several languages.

We were in the camps for 31/2 years and moved several times for no apparent reason. One camp was a gaol, and the inmates were still there! That was scary for us.

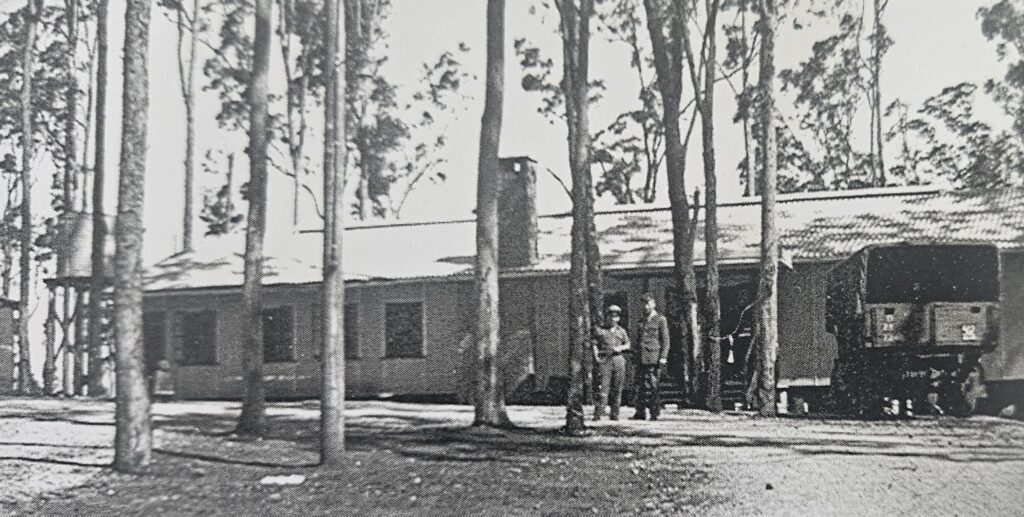

Our first camp was close to Surabaya, and I remember one camp I was in was Tjideng. The camps seemed to be old Army barracks. It was very crowded. There was very little there. The bunk space was narrow, and clothes were stored on a shelf above. We were given a mat, a fan and a bowl – usually half a coconut. That was all.

There were no toilets or paper. The food was terrible, and we all became sick and skinny. At first, we had to fend for ourselves, and many went into the bush to catch frogs etc. Later there was a central cookhouse, but the food was little and poor – offcuts of sago plants etc, very little meat, and no sugar or salt, butter, milk or bread. We were lucky: later, my mother was made a cook for the Japanese officers – so she could steal extra food for us at times.

During the day, we would be sent to work in the gardens or cookhouse or cleaning. Some of us made knitting needles from bamboo, and knitted socks for the Japanese – we were rewarded with little lumps of brown sugar, which we craved.

My sister Eva, two years younger than me, couldn’t cope. She became uncontrollable – maybe she had a breakdown – and was eventually taken away to a military hospital. Though we have searched wherever possible over the years, to this day we have no information on what happened to her. We are still looking!

We didn’t get much news in the camp. Some Javanese were employed as guards, and one would talk to us at the fence, but he had to be careful. And there was one Japanese officer who was friendly: he organized messages to the men’s camp for us. He said he knew what it was like – he had been interned by the Australians.

One day we were all summoned to assemble in the compound square. A Japanese officer told us that Japan had attacked Sydney and destroyed the centre span of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. We laughed – we knew there was no centre span. As punishment, we all had to stand in the scorching sun all afternoon.

Another time – it was just before the Allies came – we were all lined up-and our hair was cut off. Maybe it was for lice, I don’t know.

Liberation

One night, the Japanese guards were there as usual. By dawn next morning, they were gone – and much of the camp was burning. The gates were open, and some fled. But most of us gathered in our national groups, discussing what we should do.

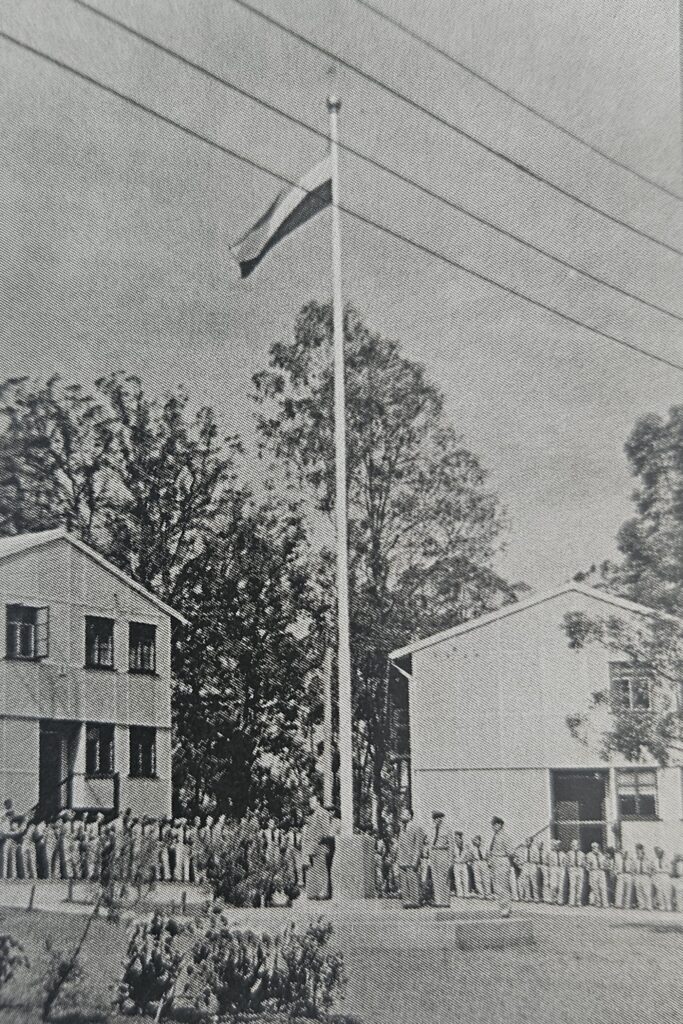

Japan had surrendered, and Mountbatten came into our camp – looking for the British first. But the Indonesians declared Independence from the Dutch too! They seized abandoned Japanese weapons and started killing the Europeans. So, the British put many back into the camps for safety.

Soon it became clear that things would not return to the pre-war situation: the Indonesian revolution had begun, and we had nowhere to go.

Refugees

After a few weeks with the Red Cross, our family of six was put on a refugee boat-the “Arcadia” I think. It sailed down the west coast of Australia, across the Bight, and eventually we reached Sydney.

We had nothing when we arrived in Sydney. First we had to walk – in our weakened state-from Circular Quay to Railway Square (three or four kilometres). Then a train took us to another camp – at St Mary’s near Penrith. They were army barracks again, but we were safe.

I remember the cook put on a banquet for us that first night. We couldn’t believe the food! We had been half-starved for so long.

But then the Medical Officer came in and swept it all onto the floor.

“Do you want to kill these people?” he yelled. “I want them all to start their recuperation with chicken soup.”

We stayed at that camp for a long time – about twelve months. There was a housing shortage after the War, and unemployment too. But we were expected to find work. I went to work for a local textile company. I had to stand all day – though I was still weak, and I developed asthma from the fibres. I wasn’t used to factory work, but I was helping my family-and at least I wasn’t afraid.

About this time I met my first husband. George Smith was an Englishman who had worked in Asia – he spoke several Chinese dialects – and he had been interned in the Philippines. He was in charge of the Red Cross Rehabilitation Hospital and housing for the personnel at Jervis Bay Naval base, but even so, our family had to share a house.

Because of my languages, I was soon working with George in Housing, and later for the Dutch consulate in Sydney. We eventually married. George was thirty five years older than me, and we only had a few years together before he died.

It was much later, in 1956, that I met Geoff at the Arthur Murray Dance Studio in Sydney. He is ten years younger than me! But he understands my history – and he spent time with the Occupation forces in Japan.

We came to Queensland in 1974, first at the Gold Coast, then Springwood – and now we have lived in Forest Lake for eleven years, to be near our daughter Jennifer.