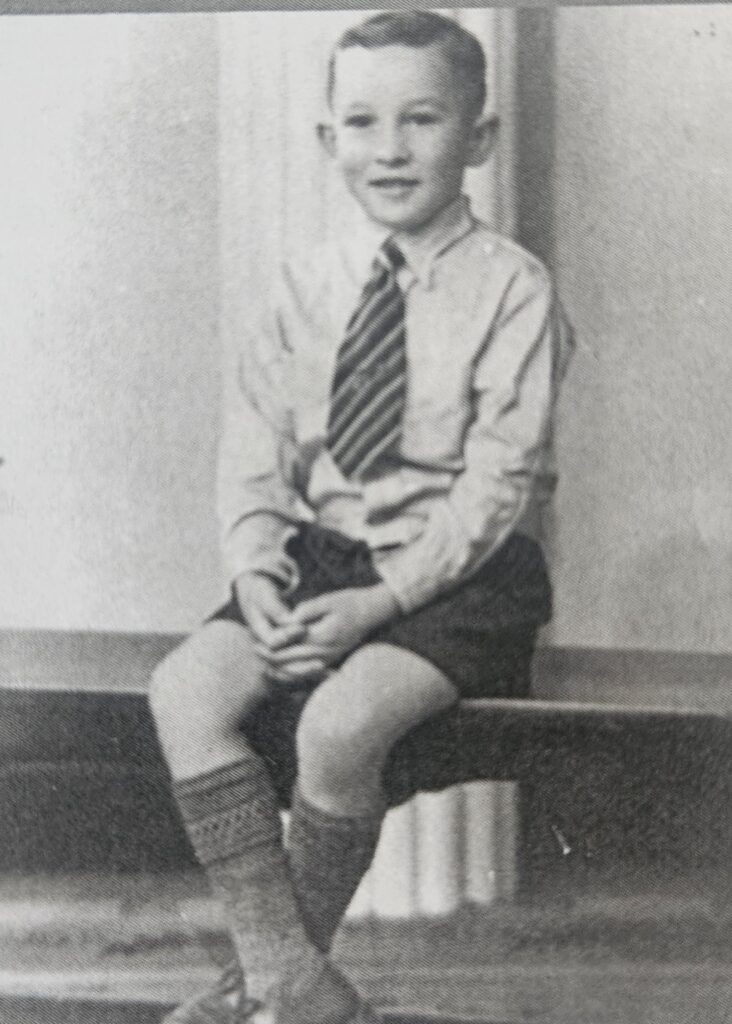

Richlands, at the time of the arrival of the Americans, was a small ‘pocket of farms to the south of Darra, with about seventy-five homes and farms, many empty blocks, and only one access road—Archerfield Road to Darra. I was one of the first babies born in Richlands Estate, and I was five when war broke out in 1939, so it meant little to me. But then in 1942, Richlands was invaded by the 636th Company of the US Army Ordnance Corps.

Richlands State School

In 1942, I was eight years old, one of about sixty children at Richlands State School. That year, we attended a school that was on a war footing, with the windows taped up to prevent glass from being blown over us. There were buckets of sand to put out incendiary fires, and many angled slit-trenches in the schoolyard. The school was supplied with two-inch-wide tape for all windows (used as up-and-down bars to prevent glass from being blown everywhere in a bomb explosion), fire buckets with a stirrup pump, and sufficient slit trench length to accommodate us plus our old teacher, F.C. Cooper. The slit trench dimensions were approximately 600mm wide, 1020mm deep, and 12m long, with a zigzag every 3m. They were revetted with good timber, with a spacer bar top and bottom. They also had child labour to bail them out after heavy rain.

I remember one student’s excuse for being late to school, which he used more than once. He said that he couldn’t get into the bedroom to get his clothes because his mother was entertaining American soldiers. So all the schoolchildren were aware of the scandal. The added rumour was that her husband stood at the door to collect the money. Reminders of war were all around us, but we still played Cowboys and Indians in the metre-high grass and bracken fern that covered at least half the school grounds.

Darra Ordnance Depot (Richlands Ammunition Dump to the Locals)

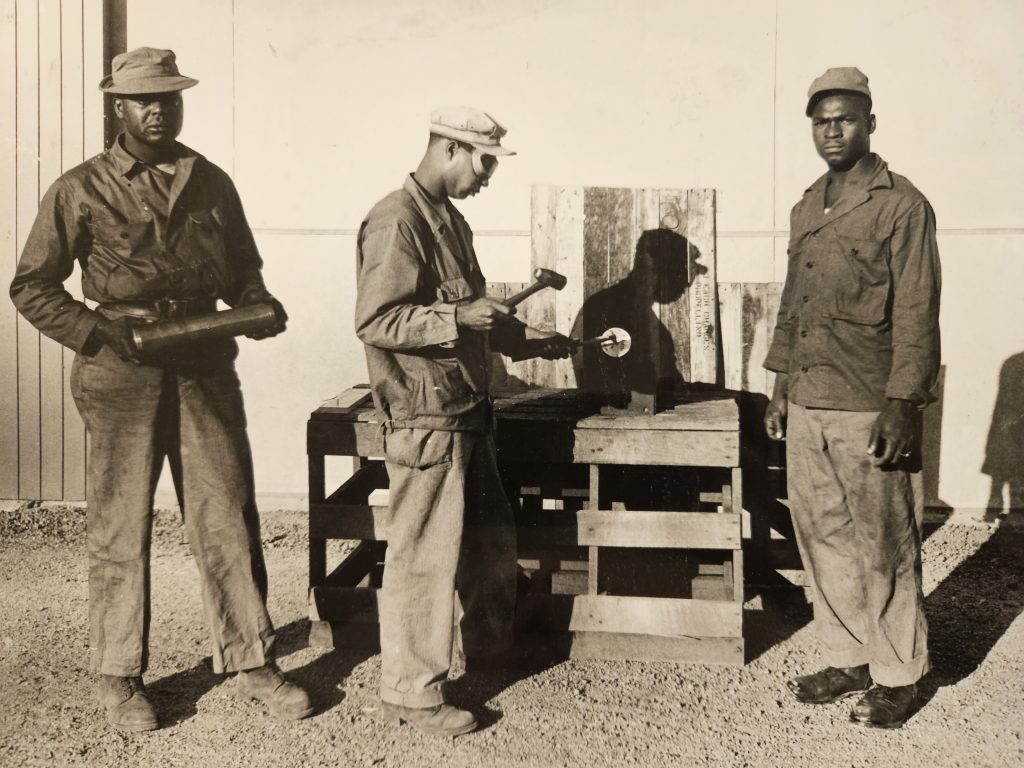

The 636th Ordnance Company of the US Army was a labour and transport group—coloured soldiers were not used as combat troops at this time. They worked within the Darra Ordnance Depot and built their camp in the area that became Serviceton and later Inala. Another company worked the Wacol rail siding used by the Ammo dump at Richlands, and more were camped in Freeman Road. Hancock’s Timber Lease (or what was to become Forest Lake) was used for the ammo dump. Reputed to be twenty square miles or more, it was soon covered in roads that wound everywhere on high ground. There were tarpaulin-covered igloo-type storage units along all the various roads, and the ammunition and bombs were stored in these buildings. Archerfield Homestead (the rebuilt cottage, not the grand old house) was used as the Command Post, handling all their internal telephone communications, and they built a 120ft fire tower about a quarter mile past the homestead. There was an immense firebreak surrounding the ammunition dump, and this was patrolled by civilian guards on horseback. Where the firebreak left Progress Road, there was a guard hut with a telephone connection to Wacol and Archerfield House. (When you are a local kid, you get to know things). At the end of Archerfield Road, just short of Government Road, they built the control gate for the ammunition dump. All ingress and egress, whether by Government/Progress Roads from Wacol or by Archerfield Road from Darra and Brisbane, was controlled from this point.

Our Playground

For my brother and me, our major playground was these local bush areas, which we had always roamed at will. Jimmy was ten years old, and I was going on nine in 1943 when we were attracted into the ammo dump adventuring. We would go through the barbed-wire fence that bounded our property, cross into the scrub of Percy Down’s property behind ours, cross Government Road, and head northeast through the dense bush to the first ammunition dump clearing (approx. Renoir Crt and Morrisit St. Forest Lake). From this site, we went to other clearings, always skirting the roads. We also wandered down to the firebreak via Government Road, which ended at that point. The firebreak was patrolled by mounted civilian guards, but as we travelled in the scrub, the ammo dump guards never saw us—and could never have caught us on horseback in the bush. Of course, we never considered they would shoot us, as we used to talk to them at our back fence and had got to know them. Our point of turn-back was when we could see the two enormous fibro buildings up the rise over Bullockhead Creek (which I now know to be the Small Arms Renovation Plant at Ellen Grove). We never crossed the road leading to them from the ammo dump. We climbed the fire tower a few times before it was burned down in a bushfire in 1946. I remember it as built in four sections high with a roofed lookout building at the top. Whenever Jim, Ronnie Armstrong, and I climbed it after the war, it had feral pigeons in it. This was very exciting stuff for two little boys. We could do these things in less than two hours, so we were never queried at home.

The Richlands Community at War

Jim Kimber served in the Australian Army, Jack Victor served in the RAAF, and Jim Gudge was also in the Australian Army. Richlands was largely a farming community—an Essential Service—and I don’t know of any other locals who went to war. It was very unfortunate that some Italian people did not have Australian citizenship and suffered internment during the war. This was strange to us because these good people were not our enemies at all. They were not naturalised Aussies, which forced them to report to the police at Oxley regularly—a 5 km walk each way, in addition to working their farms. My understanding is that some eventually volunteered for internment.

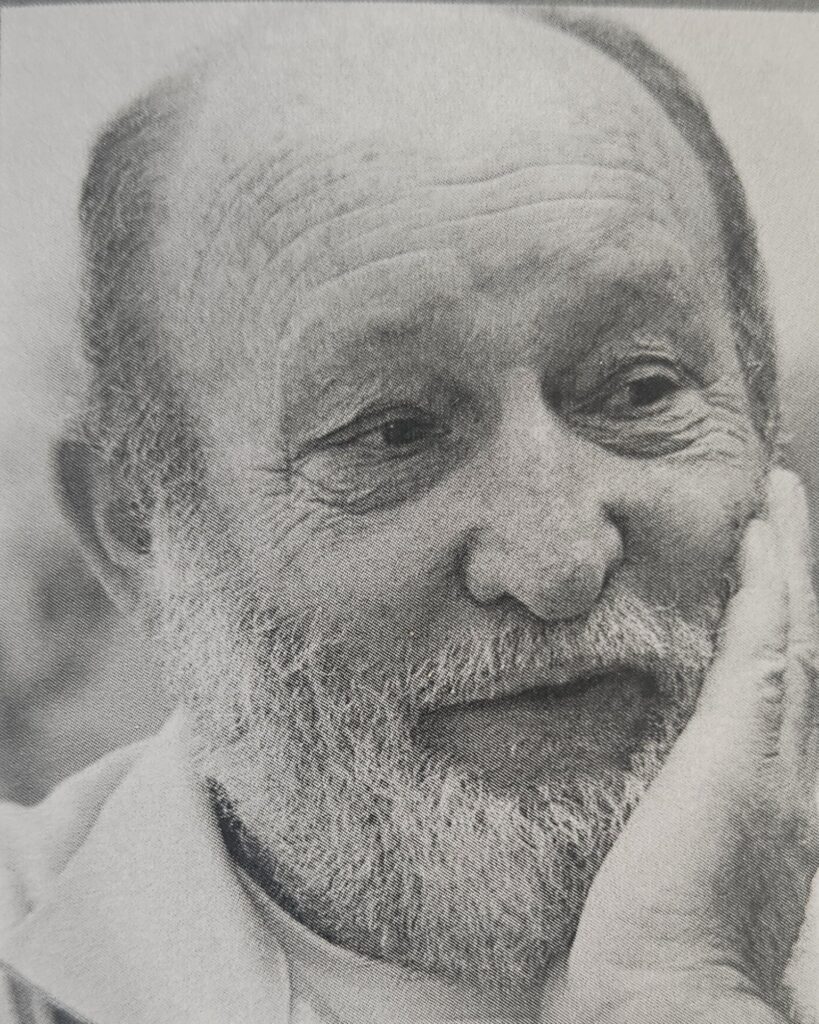

The Clark Family

Due to his age and health, my father was only acceptable to the VDC (Voluntary Defence Corps), with whom he saw 1098 days of service, from January 1942 to December 1944. He had postings like Rocklea ammunition factories, the water tower at Margate, and finally to the Torres Strait Islands—where he spent 327 days on active service. They visited most of the islands regularly on patrol by pearling lugger. He was away for almost a year. My mother kept things going. She was really good on the end of a cross-cut saw, with Jim or me on the other end—cutting into blocks the trees that Jim and I felled. This occurred every Saturday morning—and Dad was amazed when he came home at the huge amount of firewood at the back of the house. I was eight years old, with my brother at nine, and our two sisters older and younger than us, so my mother had her hands full and did not do any washing or ancillary work for the Americans, white or black. Like the other local families, we didn’t volunteer time, goods, or money to support the war effort: we had nothing to give. After the fighting moved further away from Australia in late 1944, the VDC was disbanded, as “Dad’s Army” was no longer required. My dad came home and got a job at Goodna Mental Asylum. He approached the US Army and received a permit to travel by pushbike on the Army munitions road to Wacol when en route to and from Goodna. Government Road was part of the US munitions road.

The American Way

Within days of arriving in Richlands, the Americans swiftly pushed a new road through to Wacol for rail-to-wharf cartage. The American way to build the road was very direct. Their contractors, Thiess Bros, drove their bulldozers through five privately owned properties (including ours), graded and gravelled the road, and built a bridge over Bullockhead Creek. My brother Jim and I were “overseers” of everything that was happening. A week later, an Australian Army officer knocked on our door to notify my mother that the road was going to go through our property. We kids quickly let him know that the Americans were already using it twenty-four hours a day! Sometime after this, we received official notification by mail. At the end of the war, our property was handed back. I don’t know if any compensation was ever offered: certainly none was asked for or received. My father, with the aid of his two sons, re-erected our boundary fence on its correct alignment and removed the road fence, and that was that.

American Drivers

The big trucks, heavy loads, and poor roads tested the drivers at times. I saw an amazing incident one day on Progress Road. A loaded truck came sliding along in wet weather on the unmade track. The truck became bogged down, and the soldiers went to get another to pull it out. It bogged too—and eventually, there were five vehicles bogged in a row. The last vehicle was a jeep: maybe this was an officer, because at last, there was action. The biggest man I have ever seen—a big Negro—walked to the back end of the jeep and held it up while others stuffed branches under the wheels to get traction. Then he walked to the front and did the same, and the jeep was free.

It was only then they brought in a Diamond T winch truck—which they should have done in the first place.

Australian-American Relations

The American arrival in Richlands was not an announced event. It happened, and they were accepted as being there as Australia was on a war footing. We people of Richlands got on well with the “636th”. Chewing gum was always offered to the kids by the troops. They were very kind to some of our womenfolk—and to the rest of us as well, as almost every Saturday night our family attended their open-air pictures. McEwan Park Inala, bordering Archerfield Road, was the site of the 636th Ordnance open-air picture theatre. All locals were invited to attend screenings: we sat on logs for seats, enjoyed the show, then walked home. I saw Walt Disney’s “Dumbo” among other films there. This was my first picture show—”Thank You, America.” To my knowledge, there was no conflict in any shape or form in the three years they were here. And when the Americans left, it made no difference for us children. Life simply went on.

After the War

Some of the American camp buildings were left in situ and were, in time, occupied by the people who formed the Serviceton Co-op. One of these huts was moved to Orchard Road by the Browns and is still there (in 2005). No igloos remained as they were tarpaulins: they probably went with the Americans, and the timber frames—well, I don’t know.

Bushfire

In 1946, a bushfire went right through the ammo dump. From the time I can remember, we had always had bushfires, but that 1946 fire was enormous: it swept up from way down Greenbank way. It did not threaten Richlands people directly, but to see the old Ammo dump area—”Wow” is the good word! It was unstoppable—it had a lot of fuel as it had not burnt since the 1939-40 era. The fire lookout tower went up in flames. The police asked for help to locate any known ammunition. So my brother Jim and I were thrilled to have a ride in a police car to a site opposite Bulls in Government Road, where we showed them two very big yellow chlorine gas cylinders. They used their radio, then dropped us near home. They obviously removed the cylinders before the fire got to that area because they were gone after the fire.

UXOs — Unexploded Ordnance

We did know of some big aerial flares, and we pulled them apart to get the parachute silk from them. We gave this to our mother, and she made blouses and shirts out of it. Also, I still have a scar on my hands from removing the projectiles from .50 calibre Browning (machine gun) rounds. We gathered the cordite and let it off in the bush for fun. No-one was ever hurt. The Americans got rid of the bombs and most of the ammo. Then the RAAF moved in to clean up. And the bushfires probably helped. There were broken cases of small arms ammunition spilled in some storage areas, but I never saw any large quantities at any time, and I don’t know of any ammunition being buried in the ammo dump or its environs. But every so often, even today, someone finds some…