I was born in 1927 in a Railway house at Wacol (then Wolston), the youngest of six children. Dr. Moray, a woman doctor from the Wolston Park hospital, delivered me. My father was the local Ganger—responsible for maintenance of the railway line from Darra to Goodna. He was from Roma, and my mother was from Toowoomba. They moved about a lot over the years—at Miles, Mum was the railway gatekeeper—and finally came to Wacol about 1920. There were five railway houses there in the bush along the railway line: Passmore was the Station Master, Dowsett the assistant, Krantzman and Greer were the Night Officers, and Dad was Ganger in charge of the fettlers.

There was a railway weighbridge at Wacol and a shunting line outside our house. Goods wagons would be left there overnight, often with animals—pigs, sheep, or cattle. My husband Ken was from Redbank, and the first night he stayed, he was kept awake by the stock: we were well used to it.

Wacol Memories

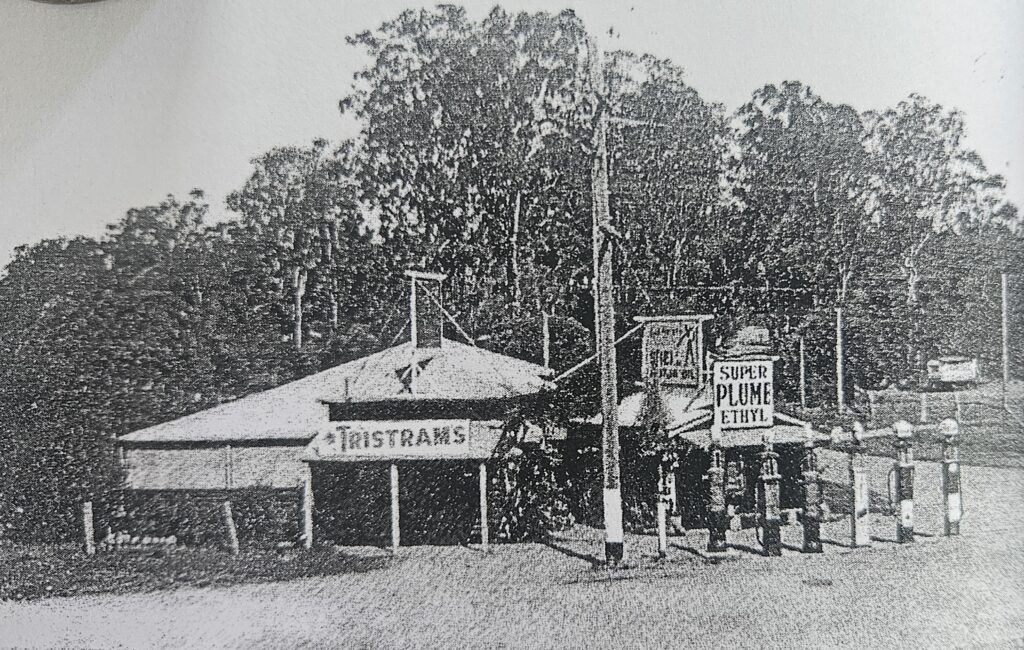

Perce Hamment had the garage at Wacol then, along Ipswich Road; that was the only shop. We had our own chooks and vegies, and the butcher, baker, and fruiterer called by in horse and carts. Any other shopping was done at Goodna. I remember Mr. Trattles ran a picture show at Goodna, in the School of Arts. The Holland clan was settled over on the verge of the golf course (my brothers used to caddy there for sixpence a game). There were several Holland families—I remember one sold honey. Mrs. “Zippy” Holland conducted church services at her home—I went there each week for Sunday school. A minister would visit every so often. Years later, we would pick up the Holland girls and all go to the dances at Goodna and Redbank. We also went to dances over at the Wolston Mental Hospital—a pleasant walk through the bush.

Like the Hollands, we had a tennis court—Dad and the boys brought ant-bed back from the bush and made a lovely solid court. We joined the Redbank Tennis Club and played fixtures up Ipswich way.

During the Depression, Mum was generous to the swaggies who called. I remember some bullock teams from out west would rest in the spare paddock next to our house. Gypsies would gather on the corner up at Ipswich Road. They would fight among themselves, and the police were often called. I first went to school at Darra in about 1935, but after twelve months, I transferred to Goodna, where Mr. Haughton and his wife were very kind. (His brother was the chemist at Oxley). I remember the slates, the inkwells, and the wooden desks.

One local game I remember concerned old tires. The girls would curl up around the inside, and the boys would roll us along the street. We didn’t have birthday parties—but there was always a present and a cake with the family. Each night I would take our billy down to a central spot near the Wacol station. Mr. Grindle had the milk run, and he would fill the billies left there early each morning. The local kids then picked up fresh milk for the family’s breakfast. Jem Grindle and I were friends at school. I remember going up to Wolston House to play—and drinking fresh milk squirted straight from the cow! Jem was a much-loved late child, pretty with curly auburn hair. She loved horses, and it was a horse that killed her—it spooked and threw her into a light pole during the war.

World War II

Australian soldiers were camped in the bush on the opposite side of Ipswich Road. We visited Redbank Army Camp quite often. Mum would bake a heap of cakes and slices, and we’d all go up to give an afternoon tea to some of the men who were far from home. The rationing didn’t seem to affect us—maybe Mum had other avenues of supply. My two brothers went into the Army. Vic ended up in New Guinea, and Jim was sent home from Townsville when his feet gave out.

The Americans

I was fifteen when the Americans came, working in the office at Coburn’s Frock Shop in the city. The owner was Mr. Massey MP. Two of my sisters worked in the factory as a presser and a machinist. My other sister was a shop assistant at David Jones, and later Myers. One brother worked at James Campbell Hardware in the city, and we all traveled by train. The American Army moved in behind the railway houses. The US soldiers disembarked at Wacol and were marched up to their camp—Camp Columbia. The camp stretched way over the hill. The Americans put in another siding to handle the huge amount of bombs and other ordnance moving to and from the big Ammo Dump at Richlands. They built a big hospital in the bush (corner of Wacol Station Road). Mum and my sister did American laundry—for the officers, of course, and they paid well. They came to the house, but none of us became involved with them. We had a blue cattle dog. He baled up a Negro one night—and my brother joked that “His face went white!” On the weekends, everyone in Wacol would go up to the camp to watch the films the Americans showed. But we didn’t see much of the soldiers really.

The Diggers and Trains

Trains to Toowoomba and beyond passed through Wacol—some of them driven by two of my uncles. A fair number of trucks went past too, along Ipswich Road—which just had room for two cars—to and from the Army camps, both American and Australian. There were quite a few accidents. But most war transport was by train. Huge amounts of equipment and materials were carried north. Troops arrived from down south by train. Australian raw recruits were taken by train from Brisbane past our house to Redbank camp for training. From the kitchen window, Mum would wave to them, and to the soldiers in the troop trains leaving Redbank for the war—and later to those in the ambulance trains as the wounded were carried back to the Redbank hospital. And one day, she unknowingly waved to her own soldier son as the ambulance train passed. It was bringing Jim home from Port Moresby, invalided out sick with Phalaria (a bit like malaria). So the railway was central to the war effort—and it was central to our lives too.