Early Days

My family, parents, and two brothers arrived from England in about 1926; my mother had two sisters here already. I was born in Beaudesert on 27 February 1927, and my sister was born two years later. Dad couldn’t get work as a jeweller here, so he bought a truck; he had been in transport in the British Army. But he lost it in the Depression—when the floods rose to six feet under our house in Buranda. We moved around a bit, then Dad bought two acres in Richlands. I think the price was £50, and we paid 5/- a month, collected by agent Mr. Dabelstein. Archerfield Road was just a sand track then, with wheel ruts and overhanging greenery; it was quite pretty. The family moved there in 1934, and they lived in a tent at first. But I had contracted polio at age four and needed daily treatment, so I was in the Marchant Home (later Montrose) at St Lucia for twelve months. But at last, I joined them, and by then Dad had built us shacks of bush timber. One was two bedrooms, and the other a separate kitchen, both with ant-bed floors. Like most of the houses in the area, they were home-made but quite well-made. I remember a neighbour built his house differently—out of packing cases, and lined it by pasting Courier Mails all over the walls. Over the following years, Dad gradually built us a nice regular house. There were no facilities—no water, electricity, sewerage, or roads. We put in tanks and two wells. One well had beautiful clear water, and in summer, we dropped watermelons in to cool them; I remember I fell in once trying to retrieve a melon. During the Depression, Dad was on Relief, working on the roads. It was paid according to the number of dependents a man had. And Dad got 2/- extra because of his skills in concreting—he was very handy. Mr. Carroll had a horse and tip-dray—it took a yard of gravel at most, but he got extra too. They would go to collect their pay at the Oxley Police Station in Mr. Dick’s horse and sulky. And on the way home, they would stop at the Oxley pub for their one luxury for the week—one beer, which cost sixpence.

Richlands School

I started school at Richlands—I think in its second year, 1935. Miss Williamson was the first teacher, and the parents had to take turns in transporting her to and from Darra Station. I remember seeing Mr. Connell sitting outside the school in his sulky, having a quiet pipe before we were let out. By the time I was twelve, I had a horse. We couldn’t afford a saddle, so I rode bareback, and that gave me a lot more freedom. When I first started work, I would ride to Darra, take the train to work, and leave the horse in a yard near the station. I tell my grandchildren that “I was in charge of music at my school.” And I was. The school had bought a piano, but the committee couldn’t keep up the payments and they lost it. So I was given the job of putting on the gramophone for the pupils to march into school. I remember the record included “Colonel Bogey” and “Officer of the Day.” The pupils had to mark time at their desks until Mr. Cooper gave me the signal to turn it off.

I played the button accordion, and when I was about eighteen, I first palled up with another accordion player—an Aboriginal fellow called “Rosie.” I went up to the Richlands school and offered to play for their weekly dance (their music was from the old gramophone). We only played there a couple of times. Later, I formed a dance band with two Englishmen. I swapped to the drums then, and we played at the school dance again to get practice. Our first payment was just 10/- each. We did improve, and the “Keith Brough Dance Band” played for years at dances, twenty-firsts, and weddings all over Brisbane. But we started at Richlands school. And at a Richlands school reunion in 1984, my school friends celebrated my MBE with me. I remember one day a bloke with a wagonette and horses came to the school. He announced that he was a “one-man circus” and would perform outside the school that evening. A lot of people came—there was not much else to do. He set up stakes on the level couch grass and formed a little ring of rope, with acetylene lamps around for light. I remember his dogs walked a tightrope, and that it was an entertaining evening. At the end, he passed around his billycan, and people put in what they could. We didn’t have much, but it was a good life.

The War

I was twelve at the start of the war. I remember reading about it and saying to my dad that Hitler and King George V should have a fight, and whoever won the fight would win the war. But it didn’t happen that way, and my elder brother Cliff joined the AIF and went off to the Middle East with the 2/25 battalion. When Australia was threatened, they were brought back and sent to New Guinea. He was wounded on the Owen Stanley track, and he carried the bullet in his side until the day he died. At school, a few of us made an air-raid shelter. We dug a big hole (easy in the sandy loam) then put logs across the top. We lay sheets of tin across the top and covered them with earth. The entrance was at one end, and at lunchtime, we would crawl in to eat our lunch. There was just room for about six of us—and often we raised so much dust we had to come straight out again.

The Arrival

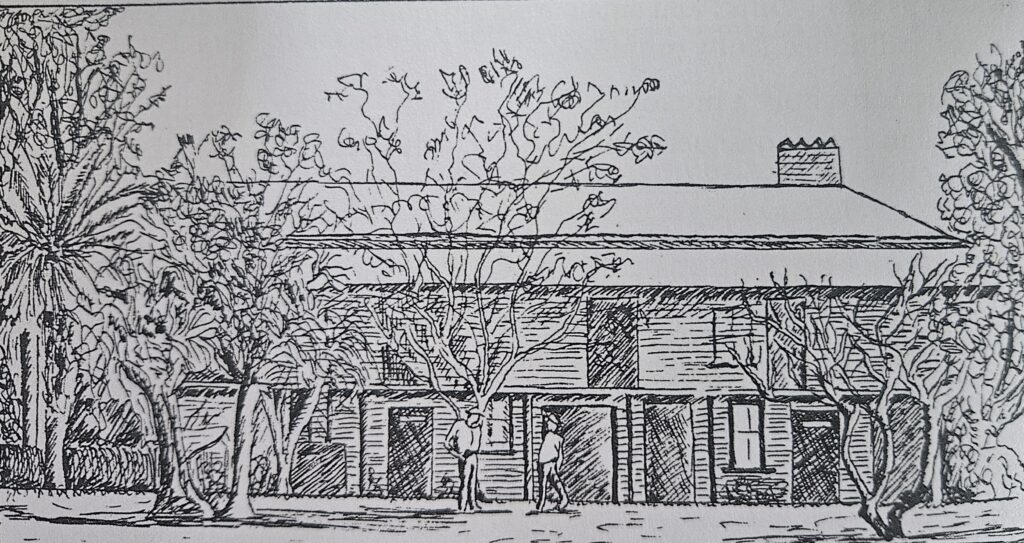

The first I knew of the US Army was one day in early 1942 when I heard, then saw 30-40 trucks loaded with ordnance coming down Archerfield Road. I had never seen such a thing! There were very few cars in the area: we used horses, bikes, and foot. The trucks stopped nose-to-tail at the end of Archerfield Road, near our house, then went on and started dumping the bombs just anywhere in the bush. In a few weeks, they got organised and put in roads and phones, etc. But some of that first ordnance was never found in the cleanup after the war. The command post was at Archerfield Homestead—an old house on high stumps, I remember. It was nearly two kilometres south of the camp, and access was just a track in from Archerfield Road, which ended at Government Road then. Trucks would be lined up for a kilometre, from the gates near our house back to the Camp, waiting to be unloaded. I reckon every type of ordnance known went past.

The Gates

I remember the first Americans to arrive—Pioneers, I suppose—had to build the camp from nothing: they had to dig a hole to keep their perishables cool. And at first, the men guarding the Ammo Dump gates were unshaven and dressed like cowboys—even tying their .45s to their legs. They always had a big fire going and were happy to chat with anyone who came along. I remember one night they had us kids taking potshots at hurricane lamps with their guns. But an officer came along and caught us out. Soon things changed. The men were shaved and in uniform.

Civilians Later Employed

Civilians were later employed by the Americans. My father was employed as a guard on the gates—usually he was stationed at the Wacol gate. There were three gates to the Ammo Dump. Archerfield Road was the main entrance, No. 1 phone. Then there was the “Wacol” gate on Progress Road, No. 6 phone, I think. The “Back gate” on Blunder Road was No. 4 phone. That gate seemed to be used only for occasional troops; everything went in and out the front gate. There were phones on trees dotted all around the perimeter firebreak, and more throughout the depot. I would guess there were twenty or more, all numbered and all linked to the communications centre at the Homestead. The Ordnance Depot was quite separate from the Freeman Road and the Blunder Road camps, and I know of no contact with Camp Columbia either. The Ordnance Corps officers soon found that an effective punishment for minor infringements was to dump the offending soldier with full pack at the Back Gate in the middle of the night. The Negro troops were terrified of the bush. And they seemed terrified of the white officers. But at times, they would ring me at the switchboard asking for a lift back.

My Work During The War

In 1943, when I was sixteen, I started work for the Americans at the Darra Ordnance Depot too. I worked on the switchboard up at the command centre. I had several horses by then, but I usually rode a particular one if I worked at night. I could leave the reins slack, and she would canter home down a little bush track in the pitch dark. They paid pretty well for those days (my salary was £240 pa), and they were good to work for. I had an ID disc with my photo and a number on it. This would get me into the American PX at the Archerfield Road camp, and some of the locals were allowed in too. It was somewhere to go. I could get cigarettes for 6d a packet, but I didn’t smoke, so I never really bothered.

Mounted Guards

The US Army employed seventy civilians as guards riding around the perimeter of the Ammo Dump. There must have been fifteen at least on duty at a time, in three six-hour shifts. Most men, each with a Colt .45, “rode the circle,” others criss-crossed the area, and the man in charge was a “rover.” They had to phone in at certain points at certain times. I had a list at the switchboard, and my job was to raise the alarm if any rider didn’t call in. I don’t remember ever having any trouble. The riders were from all over, all good horsemen and most good bushmen too. The man in charge was Dick Skewthorpe, from a well-known buckjumping family; recently I saw a bust of him in the Stockman’s Hall of Fame. The civilian guards’ quarters were at the Homestead, though there were a couple of locals who went home each night. The stables were around the mango trees, and one big long building was their mess hut. After the war, I organised a few dances up there in the mess hut. I worked in one room in the old house; there was an office in another room, and I think Dick Skewthorpe lived there. The men lived in the big American tents. We hardly ever saw the Americans up there.

The Camp

At the Ordnance camp in Archerfield Road, they built a big igloo and set it up with seats and a stage. They showed films there, and every Monday was a vaudeville-type show, with comedians, singing, and dancing—a real “legs show.” The performers were Australians, mostly professionals who volunteered to entertain the troops on nights off, so the show was of a good standard. A lot of things went on. I remember one local couple “adopted” a Negro soldier. You could see them at the shows, the men sitting either side of her—and both with their arms around her. He returned the favour by sending hotboxes of food over to her, straight from the mess kitchen. Not all husbands were so obliging. Another man came home from the war to find a new black baby, and he divorced his wife soon after.

Ammo Dump Danger

This was one of the biggest ordnance depots in the country, and there was some really big ordnance stored there—the biggest I know of was a 4000 lb bomb. There were tracers and mortars, chemicals and gas (this was over towards Wacol, I think), and small arms ammunition too. There was a factory that reconditioned faulty munitions. The Americans built a fire tower—120 feet tall—not far from the homestead, and civilian guards manned it all the time, with phone contact to the command post. A fire could have caused a catastrophe. When my brother came home and brought his Army .303, we set up sandbags in our back paddock for some shooting practice. But pretty soon, an American officer arrived and told us to stop because of the danger of a stray bullet setting off an ordnance stack. Over at the Small Arms Renovation Plant, a bloke had his legs blown off in an accident. So it was a dangerous place.

After The War

I bought my first car about that time—a 1927 Chev Whippett, which cost £40 as I remember. I went to a few dances at Darra—and played there once or twice, though they had a regular booking with Henry Eustace and Bill Lupton’s band. In June 1945, I left the Depot and went out west droving. When the war ended, we were about twenty miles out of Muttaburra, and a local stopped to tell us the news. I was the youngest, so I was left to look after the sheep while all the men went into town to celebrate. After the war, the RAAF moved into the Ordnance Depot. I came back from out west, and as I had good references from the Americans, I became a mounted guard for the RAAF. Maybe they contracted the work out, because for a time, we were paid by Luya-Julius, a Brisbane trucking firm. But they hired only a handful, and four of us (Norm Slaughter, Syd Murphy, Dave Mulley, and I) couldn’t guard the area properly. To cover the 24 hours, we worked out our own shifts. Murphy—and his blue cattle dog—lived at and guarded the Archerfield Road gate. We stabled our horses nearby. And we worked out some strategies. We would sweep the roads by tying branches and bushes behind Norm Slaughter’s horse and buggy: Norm had a good four-wheel buggy pulled by a nice black horse, which he drove down from Harrisville. Then we could check for tyre marks, and we caught a few that way. People would wait till we passed and then come in scavenging. There were still some pretty high-quality tarps there, and lots of small ammo and things. The adults stole ammo too, and some would lob a grenade into a fishing hole for an easy catch. One day I apprehended a couple of 14-year-olds with sugar bags full of grenades and small arms ammo. They could have been killed—and there were deaths over the years from UXOs that went off unexpectedly.

The Dump Explosion

The Americans had cleared a lot, but there was still a lot of ammo at the depot. We stored for the Dutch as well, and I remember there was a near disaster one day when a heap of ordnance went off. We were sitting down at the RAAF camp in Archerfield Road, having lunch when we saw smoke by the gate. We raced up there and just got the horses away before it went up. The Dutch had a lot of crates stored near the gate, mostly mortar bombs and small arms. They were well covered by tarps, but it had been raining for days, and the water must have seeped in. The problem started when it reached a Seamarker flare: they are made to go off when they get wet, to alert rescuers for a ditched pilot. One did go off, set off some grenades, then small arms ammo went off—and up it went. Flames leapt high in the air, and lumps of shrapnel lobbed everywhere, including onto our house. They evacuated the houses closest to the Archerfield Road gate. The fire appliance from Oxley stopped outside our place—and the flying debris smashed its windscreen. The explosions went on for about four hours. There was a pile of 250 lb bombs stored nearby. They were too close for comfort, but luckily they didn’t go up. I have a Courier Mail cutting showing Norm Slaughter, who was in charge that day, with I think it is the CO Flying Officer Dutton, standing amongst the ashes, with a storage igloo in the background. The RAAF’s job was to clean up the area and make it safe. The Army was called in to help. There were convoys running day and night taking the bombs, etc. away; the trucks were lined up from Pine Road waiting to be loaded. And where did much of it end up? In Moreton Bay! They were interesting times.

“More than 8000 tons of Chemical Warfare Agents were dumped east of Cape Moreton by the US Army in 1945.”

“In 1945 at Darra Ordnance Depot, a US soldier was killed, and two others were injured as a gas shell was being got ready to be included in this dumping of CWA’s at sea.”

Source: “Mustard Gas dumped off the coast” (Courier Mail, July 16, 2002, Sean Parnell)