Les: My parents were married in England, but I was born here, and I was two months old when I came to Darra in 1924.

Gwen: I was born in England in 1924 too. My father came out here first to get a job and find a house. He had a brother in Ipswich who helped him. Mum followed six months later with the three kids. We arrived in Darra in 1927 when I was three. We lived in various rented houses, then we settled in Station Road, and Dad worked at the Cement Works. My father had bought four house blocks in 1923—total 1 acre—in Maggie Jones’ Bellwood Estate (I still have the receipts), and she built a house in Chipley Street for us. He put in five big tanks, and we ran a few cows which he milked. Dad worked for the Railways—but at the Darra Cement Works. The Railways used a lot of cement, and he tested and tagged the 120 lb jute bags for them. He worked there all his life—and he was a “casual” worker all that time! During the Depression, his work was cut back—three kids, so three days of work. The poor single fellows got very little work in the Depression, and had to “hump the bluey” and perhaps “jump the rattler” (waiting up a hill for a train to slow down enough to clamber aboard). They knew where to call in to beg. But there was no thieving—and we always left our doors open.

Les: I went to Darra State School from 1931-1937. I remember a lovely teacher, Miss Singleton. She wore pretty dresses—she was the best thing about school.

Gwen: I remember being sat next to him as a punishment. But we didn’t get together till many years later. In the early 1930s, the school was closed for a time—first for diphtheria and then for infantile paralysis. As a kid, I wandered all over Darra. I knew every kid and all the local gossip. I was the paper boy for Mr. McSwan, and he would pay me a penny for every new customer, so I kept an eye on every house for rent and visited the new tenants on the first day: usually, they agreed to have the paper delivered. In the early 1930s, we had no water or electricity laid on, no street lights, or kerb and channelling. There was the corner shop (Johnson/Proctor/McSwan), The Darra Hall (Bridgewater), another shop (McElvery), a butcher (Wells), then the barber’s house (Thomas). The Post Office has been in so many places in Darra—the first was in Moffat’s store. (The first official one was a wooden building brought over from Lutwyche in the 1960s). There was a horse trough and the station. That was Darra! For a time, there was a Volunteer Fire Brigade opposite the shops (there was more land there before the extra rail line went in). All the local young men were members, and we kids would follow them whenever there was a fire. Later, they pulled the building down and used the materials to build a Church of England on the corner of Railway Parade and Gordon Street—then had to shift it because of churchgoers’ complaints about the noise from the railway! Quite a few houses were shifted in and out of Darra—in different ways. I remember one was lowered onto electric light poles, then winched along to a nearby site—and later back again! Often houses were put onto wheels—but more like a bullock wagon than a modern transporter. One house was taken to Sherwood—and it’s still there. (And they say in the 1920s, the old hall from the corner of Balfour and Winslow was moved out—and eventually ended up at Brookfield Showgrounds). Very few people had cars, so there were lots of deliveries—bread, milk, meat, smallgoods, fruit and veg—and the fisho and pastry cook. Occasionally the Rawlings man (ointments, etc.), the clothes prop man, and the knife sharpener would call. All these deliveries stopped during the war—and it never really kicked off again. The Darra Hall was in constant use—with dances or picture shows—and everyone went. We all knew each other. But I never went to any dances—not my thing.

Gwen: I went to the dances there as a teenager. Mr. Bridgewater always had a band—usually a pianist, a clarinet (I remember old Fergie), and a drummer (usually Steve Eustace). I liked the Gypsy Tap and the Pride of Erin—but often the boys would stay outside and drink. Many of the dances were held to raise funds for the football club—for 1/6 you got a supper as well—made by the Ladies Auxiliary. The railway gates were at Station Road then, and there was a wooden bridge at Harcourt Road. The Nine Foot Bridge was a wooden railway bridge: you had to be careful when you drove underneath—the clearance was just nine feet—and it was also just the width of a truck! Pannard Road ran from Canossa straight down “Convent Hill” to the Nine Foot Bridge under the railway. It was used by cars until the 1950s, I reckon.

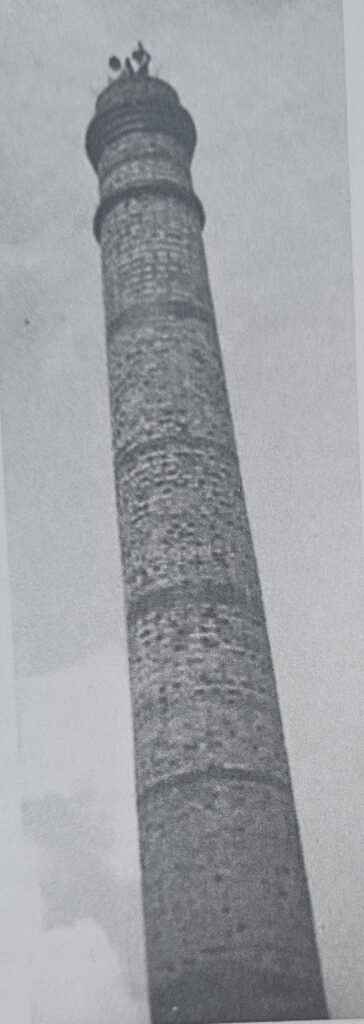

Les: I was thirteen when I started work at the Preston & Burgess foundry at the Cement Works. The foundry was later moved up to Brittain’s Brickworks—and then it was just Burgess. Next, I worked at Brittain’s Bricks and Pipes—first at the brickyard, then in the pipeyard. They had five chimneys then—and they were really high.

WWII

Gwen: My sister Ellen worked there too, and she and a friend climbed up inside one of the chimneys to take a photo—I’d say about 1950.

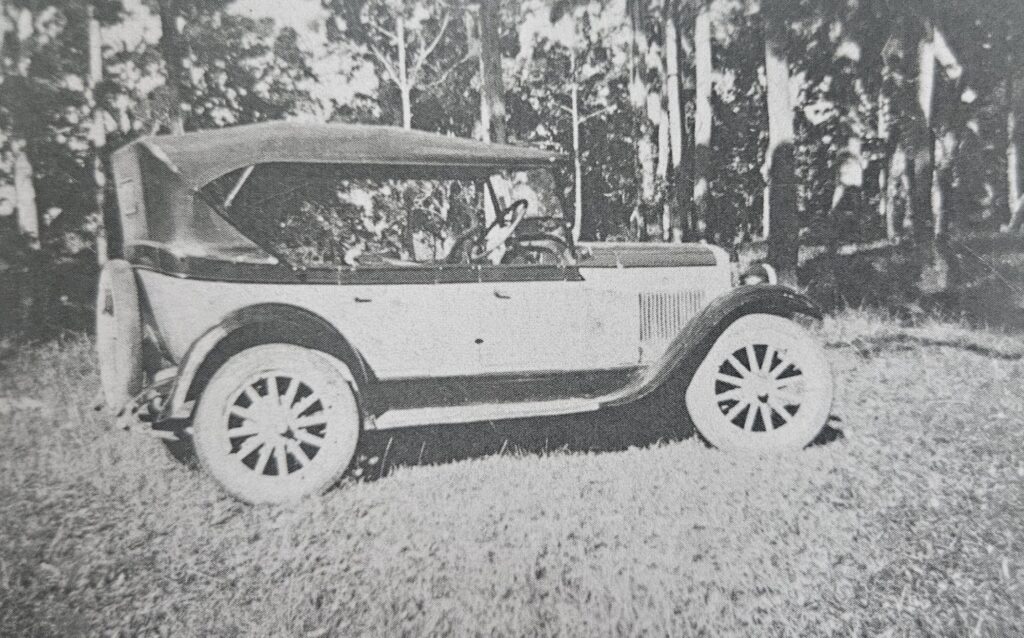

Les: When the war started, I was fifteen, and I didn’t know or care much. My parents had been through the First World War, and they were more concerned. In 1940, at just sixteen, I was making good money at the pipeworks, doing hard work. I would shovel forty tons of wet clay a day—and I earned £7/14/1 at a time when the Basic Wage was £4 per week for a married man! When I was seventeen, I bought my first car—a 1927 Chev 4. There were only half a dozen cars in Darra then, so I was a popular member of the “Darra boys” who met down at the shop. There was nowhere we needed to go, so like all young fellows, we just went on jaunts. When rationing of petrol came in, I got only four gallons a month. To extend our fuel use, we experimented with Shellite, dry cleaning fluid, naphthalene, and kero. To use charcoal, you had to make a burner yourself—I wasn’t up to that. But the Cement Works put one on one of their trucks.

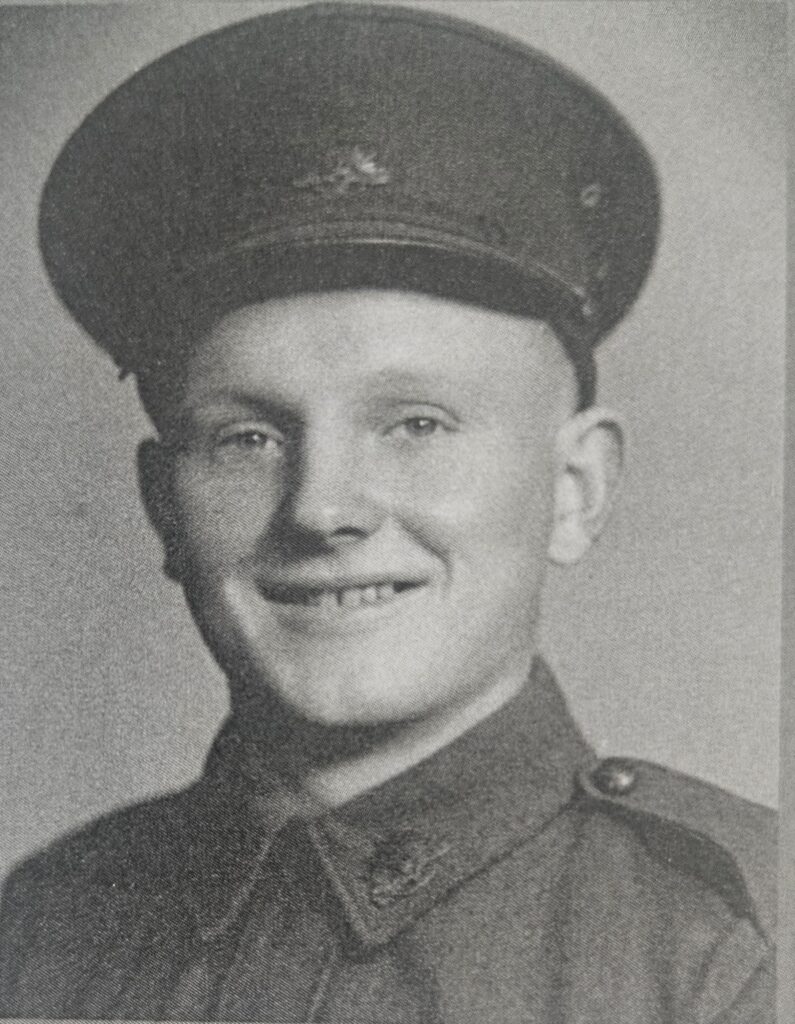

By my 18th birthday, I wanted to join up, so I volunteered for the AMF. I went in with two local mates—Noel McCormack and Syd Dobinson—but we were separated on the first day. Though I was in an Essential Service, I was in the Army before they realized.

Gwen: One of my brothers joined up, and ended up in New Guinea. My other brother was a boilermaker—an Essential Service—and not allowed to enlist by Manpower. He was needed all over Brisbane and worked really long hours. More than once, he fell asleep on the train and missed the Darra stop. One night he slept from Brisbane to Ipswich—then the train carried him back past Darra, all the way over to Sandgate and back to Brisbane before finally coming back to Darra! But several times, as he travelled home exhausted on the train, he was handed a white feather (a symbol of cowardice).

US Army

Les: In 1942, the war came to Australia. The US arrived at the same time, and then we saw lots of Negroes in Darra.

Gwen: I remember twice when my dad got into conversation with a passing US soldier. The first one ended up having tea with us upstairs. The second one he invited to go with me—not him!—to visit a friend’s farm over on the river. The man had said he hadn’t seen the river. But we didn’t go to the dances then—they had changed.

Les: My first camp was on Bundamba racecourse. The Army trained me as a mechanic, first in Ipswich, then Enoggera, then Toowoomba—and I was then posted to Chermside. At first, I was driving a truck—often delivering bombs to the bomb dump at Richlands. A shipload would be taken by train to the Wacol siding, and we picked them up there. I think we came back along Ipswich Road and down Archerfield Road to the dump. The Army had mostly Ford trucks (the RAAF had Chevs), and some were only two-wheel drive. All the roads were terrible—mostly dirt and gravel, and very narrow: Ipswich Road wasn’t much better.

Gravel Quarries

Les: Roads had a gravel pit on Dyne’s property at Ipswich and Kelliher Road. (The Dynes owned a lot of property around here). There was another on Gravel Road (now Westcombe Rd) at about the junction of Sumners Road and the Centenary Highway. Brisbane City Council’s local gravel pit was on the corner of Fonder and Bowhill Roads (that was Price’s).

The US Army took ridge gravel out from behind Durrang Street (now in Inala)—off Blunder Road, down near the creek—on De’bridge’s land, I think. Ridge gravel is a mixture of stones and clay. That’s what they used around their camps and within the bomb dump. (The Orchard Road pit came after the war, I think). During the war, we had a 240v short-wave radio at home—and Dad listened to the London news. It was an STC—a radio then was a piece of furniture, often of quite beautiful wood. Many people still had crystal radios then. In the 1930s, 4BC transmitted from Ipswich Road, Oxley (opposite the Police station). It was common to see a group of five or six people standing outside listening to the program over the outside speaker. I remember they always played “God Save the King” at the close of transmission.

Gwen: When I left school, I worked at the Oxley Bacon Factory—I rode my bike there every day. But that was just for six months, while I was waiting to go nursing. So during the war, I was in training at the Brisbane General Hospital. I came home to see the family on my days off. A few locals—mostly the girls—went to the US dances at Darra. A couple of my school friends married Americans, and at least one went to the US as a War Bride.

After the War

Les: I was in camp at Chermside on VP Day. A group of us went into town for the celebrations, and we got drunk.

Gwen: I was on duty at the hospital and hardly had time to register how important that day was. I got out of the Army in December 1946, earlier than many because of my pipe-making skills. But because I was a mechanic in a transport unit, there was plenty to do for that year. The Darra Motel—then called the Darra Universe Motel—was built in the early 1950s out of old Army buildings—probably from Wacol. And it seems the Catholic church converted another Army hut into a classroom. I bought an ex-Army truck soon after the war, and it was that truck that I used to start my gravel business.