Before the War

My Dad’s great-grandparents were local pioneers. They homesteaded The Blunder – when the first selections were opened up there in 1865. King Avenue in Durack (then Oxley) bears their name.

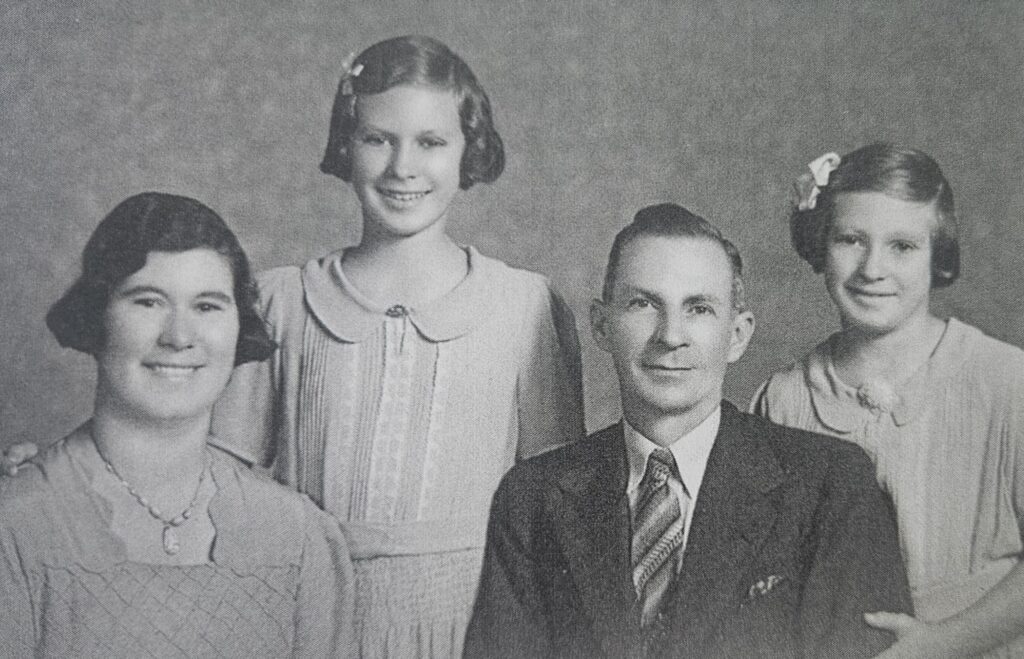

Dad’s parents came out from England as children, the Weekes from Devon, Prices from Oxfordshire. They met in Oxley and married in 1892 – making them early settlers of that area. Price Street in Oxley is named for their eldest son Richard, who was killed in France in WW1. My father, William Henry Price, was born at Seventeen Mile Rocks, Oxley in 1896.

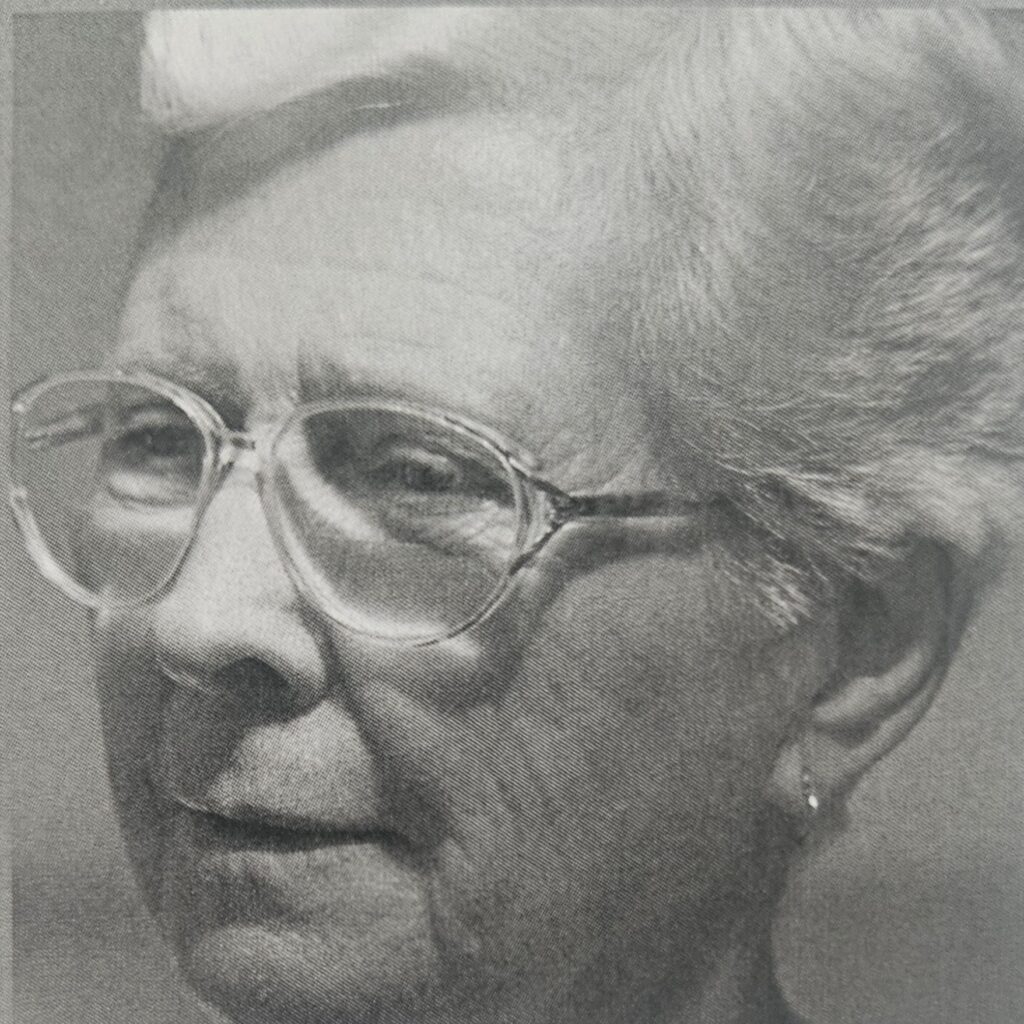

My mother, Freda Nutter, was born in Preston, Lancashire in 1907, and her family immigrated to Salisbury then Corinda when she was seven. They met and married in 1926, in St Matthew’s at Sherwood. (I was later married there too, in 1948).

I was born 9 July 1928, in my grand-mother’s house in Corinda: she was a mid-wife. My sister was born in 1932 in our house at Oxley. I went to Corinda State School. (Twenty-five years ago I started a Past Pupils Group from my era which still meets monthly).

WWII and Oxley

I was twelve when the War started. Corinda school had slit trenches dug in the grounds, and we had to practice reaching our allotted places, and then squat down in the trench until the “All Clear.” (I remember I went to Oxley school for a few weeks because our trenches weren’t ready).

We each had a drawstring calico bag, and I remember it carried a rubber cork to bite on and a calico sling for breaks. We had classes on recognising the different gases that might be dropped on us. The teachers had “clackers” to sound the alarm, but since the siren was right next to the school, they didn’t really seem necessary.

When the War started, at first it was all “Rah, Rah! We must go!” But then lots of young men from Oxley went to war, there was hardly a household that was not affected. Some Sundays we would drive up to Redbank to visit friends and relatives in training there. We were close to Archerfield aerodrome, so later, we could see the Americans practicing dogfights above us, and there was a constant stream of Army trucks along Oxley Road.

The Oxley Red Cross Group – led by Mrs Buchanan the doctor’s wife – met at the Oddfellows Hall opposite our shop, where they knitted and sewed to help the war effort. At night windows had to be blacked out. All the street names were painted over, there were no streetlights, and vehicle headlights were restricted to slits.

It all happened so fast and so many new regulations were imposed that somehow, it was just accepted.

And besides the worry about the war, there was also an air of excitement. New happenings – soldiers, sailors and airmen from many distant countries were in Brisbane: new and strange languages and accents were heard. There were movies, newsreels, dances, parties etc and life seemed to be one new thing after another.

After Scholarship I went on to Commercial State High. There we collected donations for the Australian troops – and I was chosen to write the card to the regiment we were supporting (I think it was the 7th or 9th Battalion in South Africa). The teachers went out to buy the gifts.

The Oxley Sports Centre was a social club for the young people of the district. There was no early pairing off like now – we did everything in a group. So, the boys would play football and cricket, and the girls vigoro and hockey. We would all go to the dance at the Oddfellows Hall.

Blunder Road

The family still had land at the Blunder during the war and we would go over on the weekend for wood, and to check on the cattle. In 1942 the Americans set up a camp by the creek on Blunder Road, just opposite our land (which ran from Bowhill Road to King Avenue – which is now named Inala Ave). Dad was angry that they dug under the road to tap our spring without a word.

The camp was on Delbridge’s land. The Durack Bowls Club (Delbridge Park) was Price land-and during the war years BCC bought the gravel from that site to keep gravel on the roads. I remember they had a man there every day to keep the records, and Dad was paid threepence a cubic yard. After the war, it became a dump.

I remember Mr Brough worked for the Americans as a guard, and there were mounted guards round the Darra Ordnance Depot perimeter – two men rode in opposite directions, I think.

My father had become a foreman at the Oxley Bacon Factory, and in 1943 Manpower gave him a permit to buy and run the butcher’s shop in Station Road Oxley. So, he took me out of school to be the shop girl – and I am now a qualified butcher and small-goods woman. My sister was brought into the business later on.

Rationing

There were no imports during the war, so some things were simply not available. Much of what was grown here was exported – mostly for the troops overseas. Rationing was a nuisance, but not too bad, and we were never short of food. I remember shoes took a lot of coupons. Before the war, when women went to a dance or ball, they wore beautiful evening gowns, but this ceased with rationing. Such a shame really, as everyone looked so elegant.

We knew shortages were much worse in England! Each month, Mum sent parcels to our relatives there – always including a tin of dripping or lard. And just before it set, she would push fresh eggs into the lard: apparently, they travelled quite well.

Oxley/Corinda

Shortages continued long after the war, and one good source of clothes and more became the Army Surplus stores.

It was illegal to trade ration coupons, but it made sense to do it. We made our own clothes – and Mum bought parachutes to make blouses and ‘Underpants. So, Dad sent clothing coupons to a friend on the land, and he sent down his meat coupons (he killed his own meat). Then Dad could help out local families. Everyone in Oxley knew and helped each other.

We took the coupons from the customers, then Mum had the tedious job of pasting them onto sheets and taking them into town to the Rationing Board every couple of weeks. Also, in those days there were no local banks, so Mum had to go to town each week and lug home enough change and notes for the week’s trading: imagine the weight of the pounds, shillings and pence.

Food

There was no shortage of meat. We sold at least 100 sheep a week-everyone ate mutton then. We sold only about 2 lambs as they were expensive, maybe 2 pigs and 3 bodies of beef (cut into forequarters and hindquarters).

All this meat was cut and sawn by hand – no power saws in those days. It was hot and heavy work. We made our own dripping and lard, plus about 100 pounds of beef sausages each week – which always sold out quickly. We also sold a few rabbits.

Chooks then were for eggs – and most families had their own: we had 30-40 Leghorns in a corner of the back yard. I remember there was a poultry farm on the corner of Rudd Road-and Dad was an amateur poultry judge.

By WWII we had a walk-in freezer at the shop. There was no refrigeration at home, just an icebox, and the Ice Man (Lido) came every day. And I remember even before that, we had a hole in the earth under the house, with a pottery dish. In summer, we would wet the soil, put the butter in the dish, put on the lid, then cover it all with a wet Hessian bag. We also hung a wire meat safe under the house for cooked meat – and the breeze kept it all at a reasonable temperature.

The Coloured Americans

The only black I had ever known was “Snow” Fraser – the blacktracker at Oxley Police Station. He was a lovely gentle man, tiny with white hair – and everyone held him in high regard.

But the arrival of the Americans in 1942 brought dozens of Negroes from Camp Freeman wandering around sleepy Oxley. They seemed a bit cheeky: maybe it was their youth, maybe it was the sudden freedom. We felt intimidated as they were an unknown factor. But we were curious too, for the same reason.

They approached the girls – and some weren’t averse to the attention. I know of two rapes – and while that happens with armies everywhere, white or black, our tiny community was devastated, and the Progress Association complained. We did not see blacks in Oxley after that.

The Big Shootout

Events like this were suppressed at the time – publicity would be bad for morale. But I know about this incident because it was local and my father and my husband were both involved.

Bryan was on duty at Camp Columbia that day-in late 1943, I think.

Sergeant Lewis at Oxley Police Station got a call that about twenty drunken coloured soldiers had taken over Lobegeier’s store at the corner of Blunder and Ipswich Roads. He called Dad, who was the local ARP man, to go down as a witness. All the people from the Oxley hotel and Hart’s garage were out peering through the fence.

The men had guns and the situation was out of control, so the MPs called Camp Columbia, requesting a jeep with a machine gun mounted on it. Bryan brought it down and was very relieved that the MPs then took over. The store owners crept out the back door.

The MPs gave a warning “Give up and come out or we’ll shoot,” which was answered by gunfire. So, they opened up, and riddled the place with machine gun fire until there was no response.

The survivors were sent to the front line in New Guinea.

Blacktracker on track

There have long been rumours of Japanese paratroopers being dropped in behind the Blunder, and definite reports that the soldiers at Darra Ordnance Depot were unusually all armed for a short time. Things soon returned to normal there – and it has been suggested that the Japanese had neither the capability nor the capacity to bring paratroopers here. This story has never been officially confirmed. But it was told to me by people who should have known.

It seems that in 1943 a local farmer’s dog found a Japanese parachute that was only partly buried. The alarm was (very quietly) raised, and Snow the Oxley police blacktracker was quickly brought in.

By nightfall, Snow had tracked down two or three Japanese paratroopers: Archerfield Aerodrome seemed to be their interest/objective.

The American NCOs

When the Officers Candidates’ School was built at Camp Columbia (in late 1942-43), the NCOs rented the Oxley Progress Hall in Station Road for their club (the Officers of course had a club on the premises). The trucks brought men down from Wacol and returned them to camp at midnight every night.

I noticed the Americans had better clothes – and the soldiers would have their uniforms professionally altered to fit. They were proud of their appearance in a way the Australians weren’t.

Occasionally, they would have a big Army band and it could be heard far and wide, but generally it did not cause any trouble as they usually played on a Saturday evening.

One of the older NCOs came to the house to pick up the pressed meat loaf that Dad made for their sandwiches. Then one by one, others came to the house as well.

We had a piano and my mother had a glorious soprano voice, so we had nightly sing-alongs. A couple of NCOs played piano and Bryan played the guitar. My sister and I enjoyed the peanuts and candy bars they brought us. I was not sixteen yet and I remember those days well.

On special occasions Mum would cook wonderful meals and sit the soldiers down to enjoy home-cooked food, which was a real treat for them. We also had fold-up cots on the verandah so they could relax in a home atmosphere when on a week-end leave. I remember that she would boil dozens of eggs in a kerosene tin on the wood stove, then send my sister and me to the club with them so the “boys” would have something to enjoy with their drinks.

My parents were also wonderful to our own Australian local boys who had joined up: Dad gave each a gift of money before they left the community for overseas – and another when they returned.

The end of the war

On VJ Day (August 15, 1945), Bryan was on guard duty at Ascot Camp -Camp Columbia had closed in July. But Mum and I went to town, and we had coffee with him.

I remember the crowds of people laughing, crying, singing and dancing in the streets. They waved balloons, streamers and flags. It was amazing and exciting and the relief was almost palpable. It really was overwhelming and is difficult to put into words.

I was seventeen when Bryan left, and he said my Dad was too good with a knife to broach the subject of our future, so he simply promised me he’d come back straight away. We quietly wrote and looked forward to his return.

The Lona and Bryan Story

In the beginning

When I was to have my seventeenth birthday, Mum was keen to have a studio portrait taken (she had one of herself at that age). But photographic studios were not permitted to use film for civilian portraits during the War. You could buy film for small cameras such as Brownies, but studio film was reserved for service men and women.

The President of the NCO club (Bryan Grantham) suggested that Ipswich photographer Mr Whitehead – who did many Camp Columbia photos, might do it as a favour for the US Officers. Mum agreed that he take me up to Ipswich.

Mr Whitehead said “No!” to my portrait. But eventually he suggested he take us together. I was mortified, and said “I don’t want my photo taken with a Yank.” (Insult to injury as Bryan was a Southerner, and so a Rebel not a Yank!).

But Bryan convinced me that his mother would like it (my mother wrote to her, and several other American parents too). So, we had the photo sitting, then had to go back for the proofs, and then I agreed to go to the pictures after the last visit. So, by July we were going steady – and in October he was sent home.

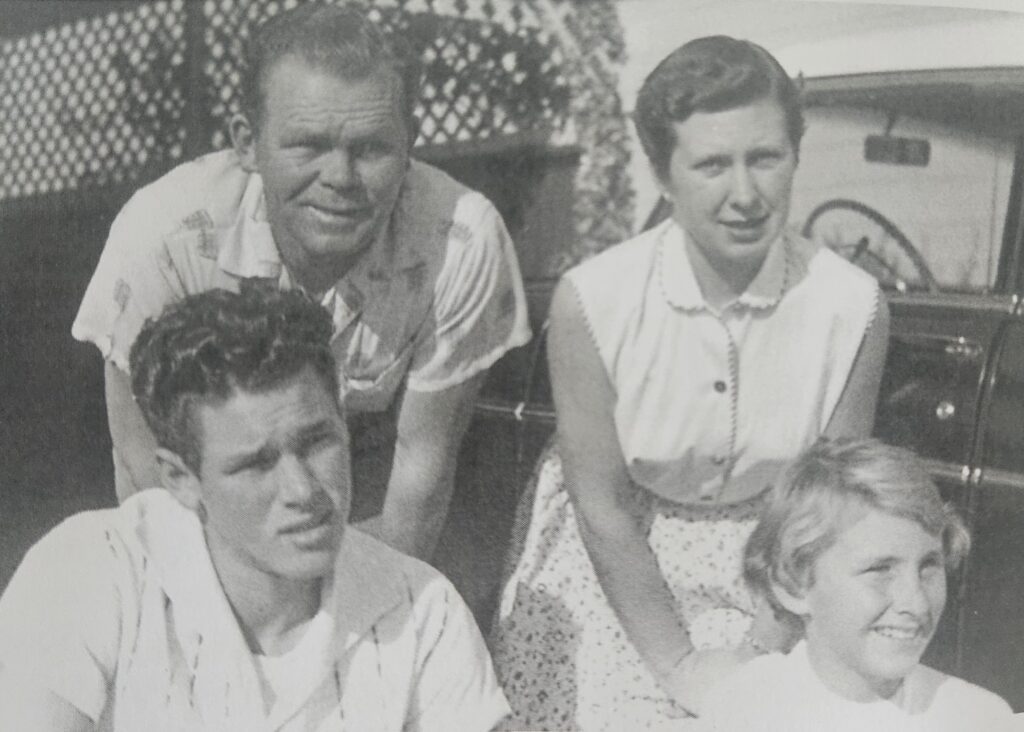

Bryan’s return

When he got home to Mississippi, there was no trace of him in the house. His family, notified that he was dead, had cleaned his things out, and his mother was in poor health. And the $3000 he had sent home as savings was gone.

So, it took almost two years for him to find work and save enough to return. When he arrived in June 1947, he stayed with us and got a job. We were engaged in July on my nineteenth birthday and married the following February, on Valentine’s Day.

In Oxley

In late 1947 we bought land near Oxley Station, in Ardoyne Road, and my builder uncle Byron Stolz built our house – it took eighteen months as materials were still restricted eg he could only get two roofs and two baths a year.

Dad wanted Bryan in the business, and he agreed. I was sceptical, but we all worked hard, and built up the business until we were making 1200 household deliveries a week – to Richlands/ Serviceton/ Darra and to Oxley/ Corinda.

In The States

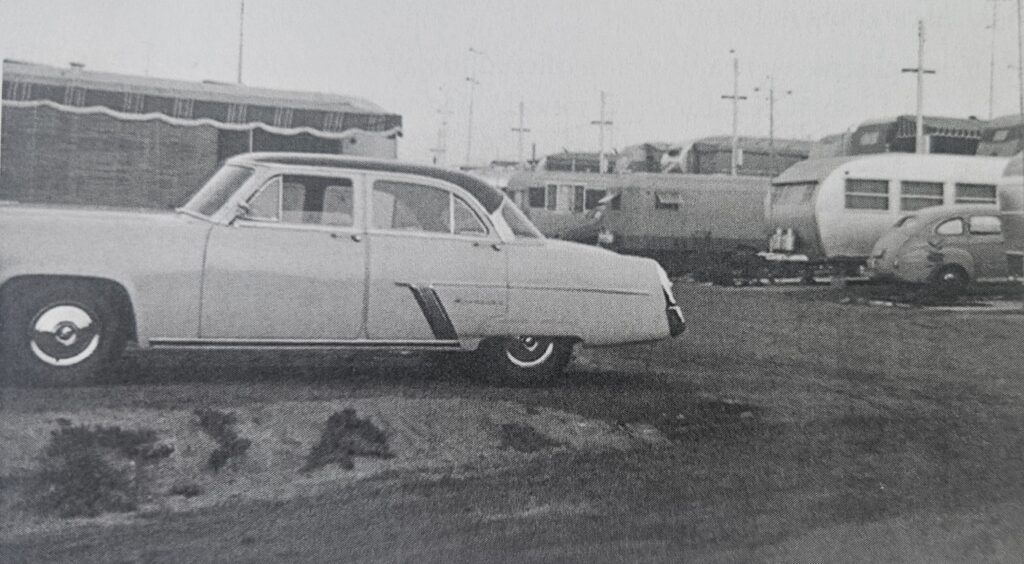

But eventually they fell out, as I knew they would. When Bryan came home after finally quitting, I said “Do you want to go to the States?” He had two questions for me: “Are you serious?” and “Are you packed?” It took eight months to get the paperwork organised, and then we sailed on the Queen Elizabeth to New York via England. It was 1951 and I was twenty-two.

So, we spent twelve years in the US (1951-63), mostly in California. In 1960, the Union sent Bryan to Nevada, to work at NASA’s atomic test site – and after checking the equipment he was the last one out before a blast. Timing was all secret, so if he didn’t come home, I knew there was a blast – or a disaster.

In that time, we adopted Bryan’s brother’s three children, so at twenty-eight I had two teenage children and then a baby. We all lived in a three-bedroom mobile home for a time-in all I have moved twenty-six times!

I took out American citizenship in May 1959. There was no dual citizenship, and even to vote at the PTA you had to be an American! I enjoyed my time in the States, and each year I still celebrate 4th of July and Thanksgiving. This year there were seven of us here, talking over old times.

In San Diego I knew quite a few girls who had come over on the bride ships. We had an Aussie-New Zealand Brides Club which met once a month, and we would take along Aussie goodies such as lamingtons, scones, passionfruit tarts, pikelets and such.

I think I am the only one of that group to return to Australia – but not all marriages between Aussies and Americans were happy. In addition, local War brides were generally not accepted in US coloured communities – and the mixed marriages were not fully accepted by the locals here either.

Return to Oxley

In 1957, my parents took a year off to travel and spent six months with us. Gary and Cheryl were delighted with their grandparents, and we all went on a wonderful camping holiday.

In 1960, my parents were ailing and offered to pay for me to come home and bring the new baby Craig for three months. It was lovely to meet family and see how things had changed – e.g. Inala had appeared in the bush – but I missed Bryan and Cheryl and was glad to get home.

Things were becoming stressful at the Atomic Test Site, and my daughter suggested we all come to live in Australia. My son and his girlfriend agreed to follow, and so we four immigrated in 1963 – and came back to Oxley. I remember Bryan’s tools took up our whole family allocation of free transport of belongings. Once more, we began a new life.