Darra Before the War

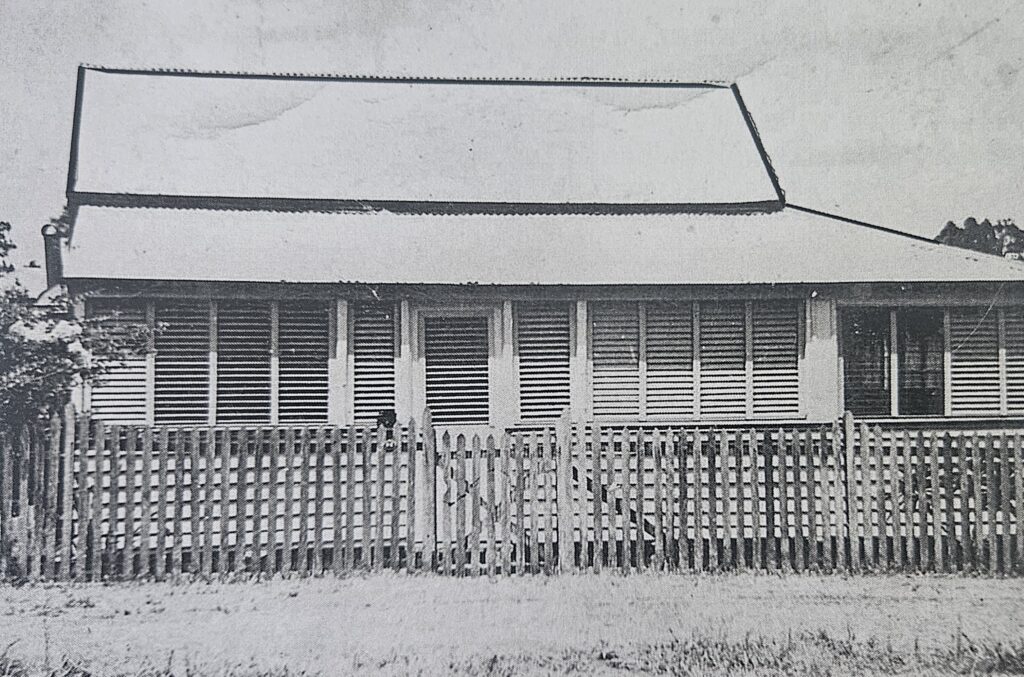

Both my parents were of Irish extraction, from families who came to Ipswich (which was then expected to become the capital of Queensland) and then to Grandchester in the mid-1800s. Both were born here—Father in 1878, Mother in 1893. I was born in 1923, at St Mary’s Hospital in Ipswich, and my family moved to Darra when I was three or four—about 1926. My younger sister and brother were born in our house at 86 Rowe Street; Nurse Burns covered the district on her bicycle. I went to Darra School from the age of four, and then on to St Joseph’s Convent at Corinda until the Scholarship year. During the Depression, my father had only about two days of work a week, and when he collected his Relief pay at the Oxley Police Station, he met men who had walked from Ipswich! For extra income, Dad worked for Scotts, who had a local sawmill. He was felling trees for them, over Richlands way. There were swaggies about then. One called at our house twice every year, and Mum always gave him food and tea. Dad called him “Fixed Deposit.” My first job in 1937 was in Milton at Morrows biscuit factory (later Arnott’s) — for 10/- a week. After the 3/- train fare, there was only 7/- left, and that money was important to the family. When my sisters started work too, we would all be rushing to catch the 6:30 train in the morning.

Neighbors said they knew if they were in front of the Hogan sisters, then they would not miss the train. Darra before the war had only a few shops—butcher, shoe repairer, two general stores (owned by Proctors and McKelvies), and a dance hall. The Station House was right there, so they could open and close the swing gates for the trains.

Darra Dances

There were regular dances at the Darra Hall run by the owner, Mr. Bridgewater—often the whole family would go. Dancing was a major social activity—I remember on occasions a couple would bring their baby, and it slept happily under the seat while they danced the night away. Mrs. Kelly played the piano and Henry Eustace the drums. Some of the older people would play euchre at the back of the hall, and when we had supper, the children would all slide around on the polished floor. Darra Hall was known to have a well-sprung floor for dancing. Twice a year there was a ball held to raise money for the Ambulance Service. Then we really got dressed up!

World War II and Darra

Until World War II, Darra was very small. We all knew each other and mixed in well. We didn’t really worry about the war until 1942 when the Japanese came close to Australia—and especially Queensland. Then there was a cousin who became a POW in Crete, and the man who lived opposite who was at El Alamein (while his wife at home looked after six kids and a nephew). It became real then. Several of my friends were called up. One Darra mate, Ernie, sent me a unique Christmas card from New Guinea. It was a piece of aluminum from a crashed plane, etched with a couple dancing, “Merry Xmas”—and “Remember the dances.” I still have it. I changed my job to the Oxley Bacon Factory in 1943. There were locals there that I knew, and we were picked up by a bus at Oxley Station. There was often war work—overtime, but we were treated well there. (I was later offered a job working for the Americans at Somerville House, but I decided against it. I didn’t regret the decision.)

The Americans

I remember when the Americans came. At first, we were impressed by the soldiers—some from the American Army Air Corps at Camp Columbia came to the dances at Darra. But the Americans were used to segregation, and black and white soldiers would fight terribly, so the US authorities declared Darra a “black” area. I was nineteen then, and my friends and I stopped going to the local dances and took the train into Brisbane to the dances there. The Trocadero became black too, but we often went to the Coconut Grove in Adelaide Street—and the dance at Redbank was good too. We were a bit scared of all the soldiers. Several of us were followed, and our parents started to come and meet us at the station. We found handprints on our windows several times. And my sister and young brother were frightened one night when a big black man just walked into our house. They took off! He didn’t steal or spoil anything, but we started to lock our doors and windows—we had never done that before. The younger local lads—14-18—would gather on the steps of the shop for a chat. We knew them all, and if we caught the last train, some of them would see us home safely. I have thought since that these Negroes were used—taken away from all they knew, put into the Army, and sent across the world as laborers, maybe to be used as cannon fodder. But then we didn’t know what to expect—and this spoiled Darra for us. But not all the locals were scared of the Americans! Two of my best friends married Negro soldiers here and went to the US as war brides. But they found the segregation and poor living conditions in America hard. One had her first baby here, in 1943 I think, then later followed her husband to America. She came back to see family twice—but on the second trip, she actually died on the plane on the way over.

Boundary Riders

We heard that the American Army wanted boundary riders for the Richlands ammo dump—men who could both ride and supply their own horse. The pay was good! My father was a retired stockman. He had a horse, which he had broken in himself (I watched him, slowly flicking a bag onto and off its back). He kept the horse in a paddock next door, so he was well qualified and happy to apply. (He had been head stockman on Brunette Downs in NT, and when the owner Al Cotton won a contract to supply horses for the British military in the Boer War (about 1900), Dad and his two brothers had gone to South Africa with the horses. Somehow he joined the Constabulary there—we have a photo—but I don’t know how long he stayed. He went back to Brunette Downs for a time when he returned, before coming home to settle in Grandchester). So with other horsemen who were over age for the army, my father (who was over sixty) became a boundary rider at the Darra Ordnance Depot for a couple of years. The guards didn’t ride together—each man rode a solitary trail. There was no uniform—I remember Dad wore his own large-brimmed Aussie hat. He always rode a grey. I can remember seeing him ride off down the road—he always looked good in the saddle! And I remember the whole family walked over to Richlands one day to have morning tea with Dad at the ammo dump. Maybe there was accommodation there too. Some of the men weren’t locals: I remember Dad’s friend Charlie Law was from up behind Tewantin. He came to Christmas dinner, but he didn’t live in Darra. And they must have worked shifts—the place had to be guarded at night too.

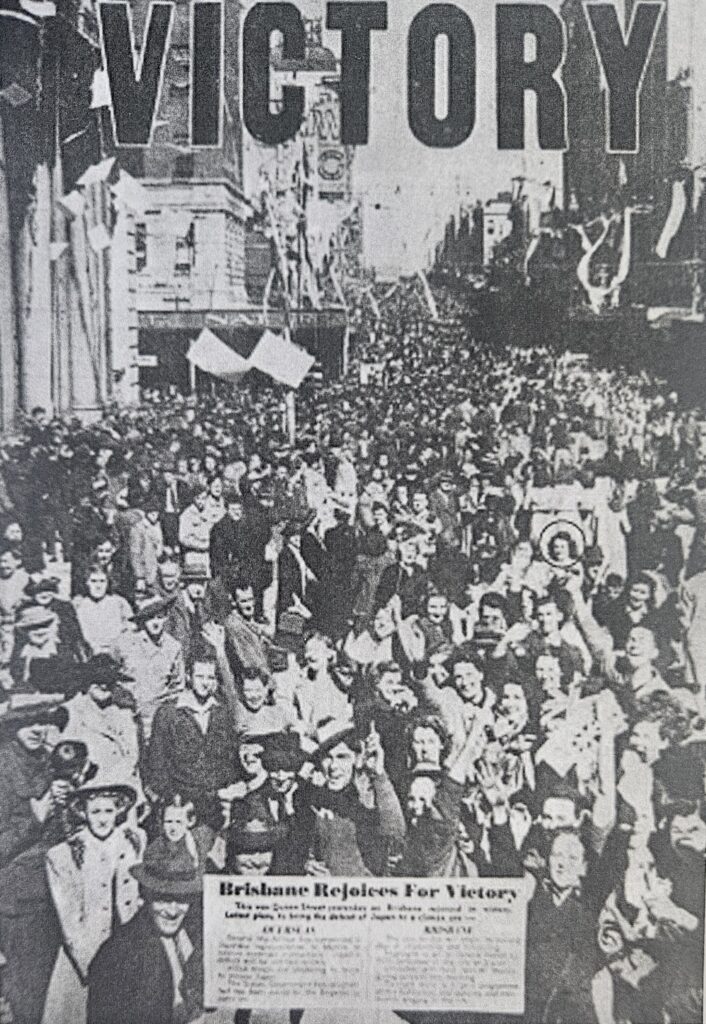

VP Day

I remember VP Day very well. My sister and I were in the crowds in Brisbane, caught up in the excitement. We can be clearly seen in that great Courier Mail “Victory” photo of thousands celebrating in Queen Street. But I remember later sitting on the front steps at home, wondering what was going to happen next. I felt sort of empty—the war had been at the center of our lives for so long…