Parade

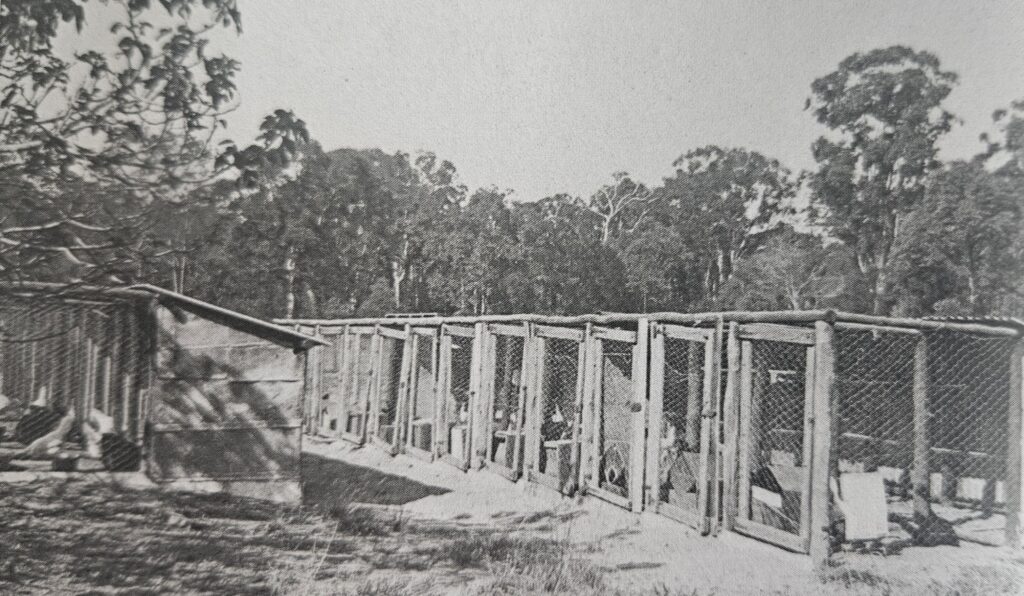

My grandfather Robert Burke Sparrow was from Sandgate. He worked at the Ipswich Railway Workshops, and he bought land for a “hobby farm” in Richlands from the Dynes about 1910. He retired there to his poultry farm on Archerfield Road. Dad (Howard Sparrow) was born in 1904, and he worked with my grandfather on the Richlands farm until sales dropped in the Depression. Mum (born in 1911) was a city girl, from Petrie Terrace. She met Dad through Auntie Beattie, who she met playing basketball (netball). They were married in 1929, and then rented a house in Freeman Road, Richlands. I was born on 14 March 1931, at Lady Bowen Hospital, and my 4 sisters followed.

School

I started school in 1936, and went to Richlands State School until 1941, then came back again later. I have some good memories of those days. The school was a small building, and they had a wind-up gramophone on the verandah. Each day we marched into school to the tune of “Colonel Bogey.” The school committee held a Fancy Dress Ball most years. In 1936 or 37, Daphne Hyde and I went as a bride and groom. Aunt Beattie made me a full “swallowtail” suit—with braces and gloves—and I still have it. The mobile dentist set up his chair on the verandah one day, and I had a tooth pulled: it was traumatic! And when I got home I was in trouble because I had forgotten my little sister Mary. She had had a tooth pulled too! I remember a visit from the Department of Wildlife who brought a display of Aboriginal artefacts around the schools, and I remember Dad came to the school one day with a Relief gang cutting the grass. Grandma would take us back to school on Sundays—she ran a Sunday school under the school building. During the war, we had to have air raid drills. I still remember the sloppy mud in the bottom of the slit trenches.

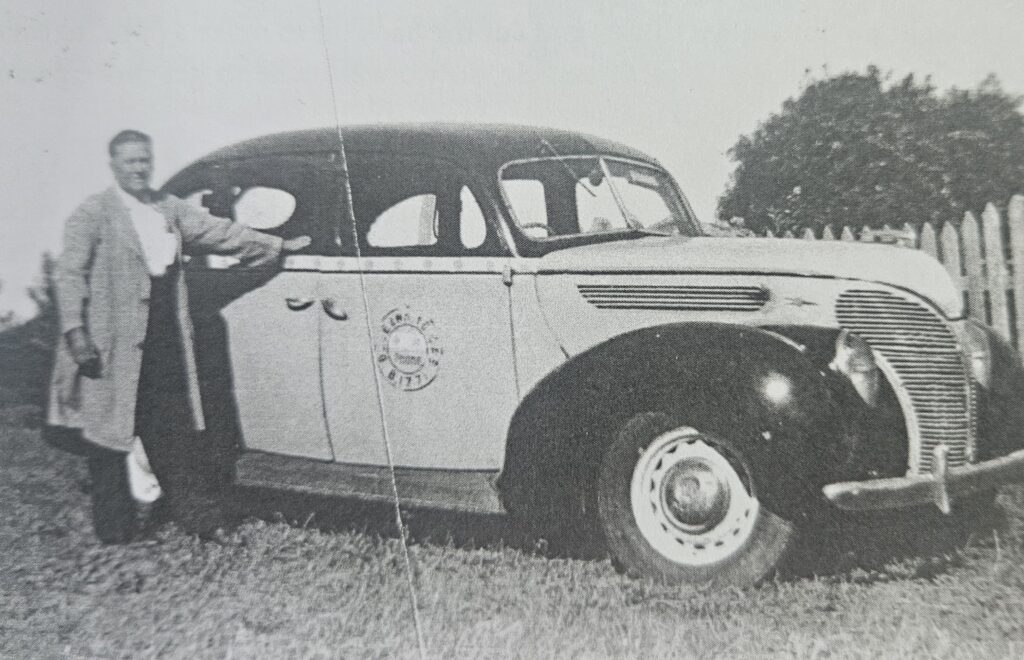

WWII Taxi Driver

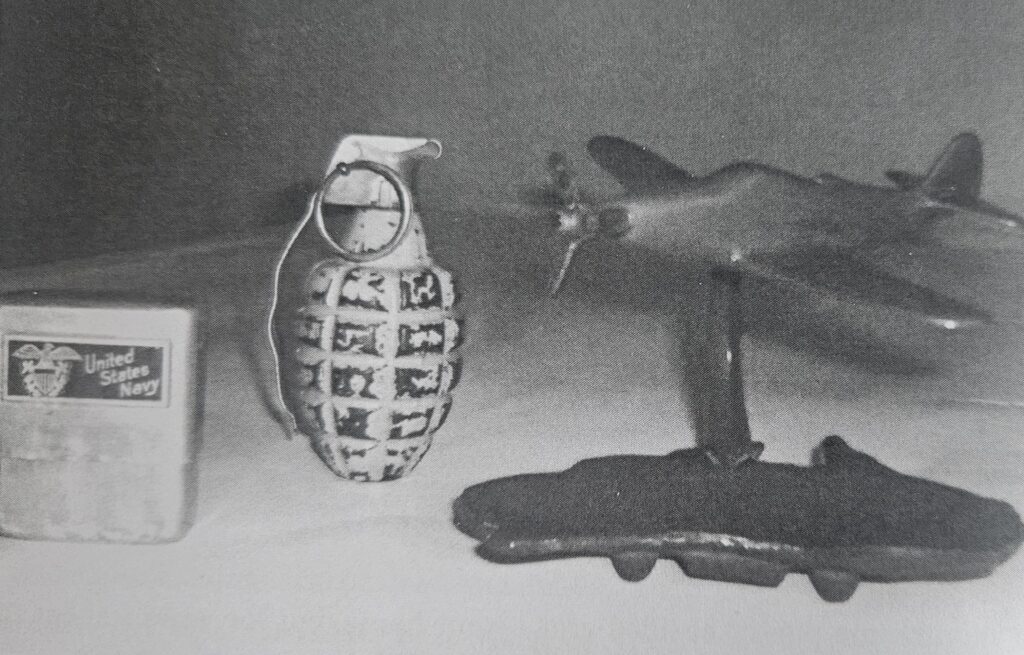

Dad had a lame leg, caused by a childhood accident, so he could not go into the Army. He did Relief work for years. Then in 1941, he was offered a job as a taxi driver in the city. Most able-bodied men were away in the forces, which gave him an opportunity. So we rented in Red Hill and then moved to Milton. It was my job to clean the taxi each night, and I never knew what I’d find left behind. I still have a US Marine Corps Lieutenant’s cap, and an aluminium US cigarette packet container (made in Illinois) that I found more interesting than the small change I discovered in the back seat.

I also have an expended US practice hand grenade (they were painted yellow, and so called “pineapples”), and an ashtray the soldiers called “Wings over Australia.” It was a map of Australia curved up to take ash, with a model Airacobra plane above. It was cast brass, made at the Richlands camp and given to my Aunt Beattie by a visiting soldier. An Army sergeant neighbour used Dad’s concrete ramps to service the Army jeeps he brought home—and from that time I loved them. Later I fully restored one, and I was in the Military Jeep Club for many years. In the 1995 “Australia Remembers” celebrations, the Jeep Club took part in a re-enactment of the 1941 US Pensacola fleet landing at Eagle Farm, and of a Troop Train leaving from Exhibition station (there was an army camp there during the war). Dad bought an old Dodge tourer and cut the back off to make a “ute” to carry things. This qualified as a farm vehicle, so we were able to get more petrol. Taxis were strictly rationed for petrol. Soldiers—mostly American—were the bulk of Dad’s passengers. He told us of one big fare—a group of coloureds he drove from town out to Wacol. When they got there, a big fellow took out his knife and rubbed it up and down his arm. “We paid you in town, didn’t we?” he said. “Oh yes,” said Dad, and drove off quickly.

Back in Richlands

With the fear of invasion in 1942, I was sent back from town to stay with my grandparents on the Richlands farm, and back to Richlands school. After a few months, the panic subsided and I went home, but for years I spent my holidays on the farm.

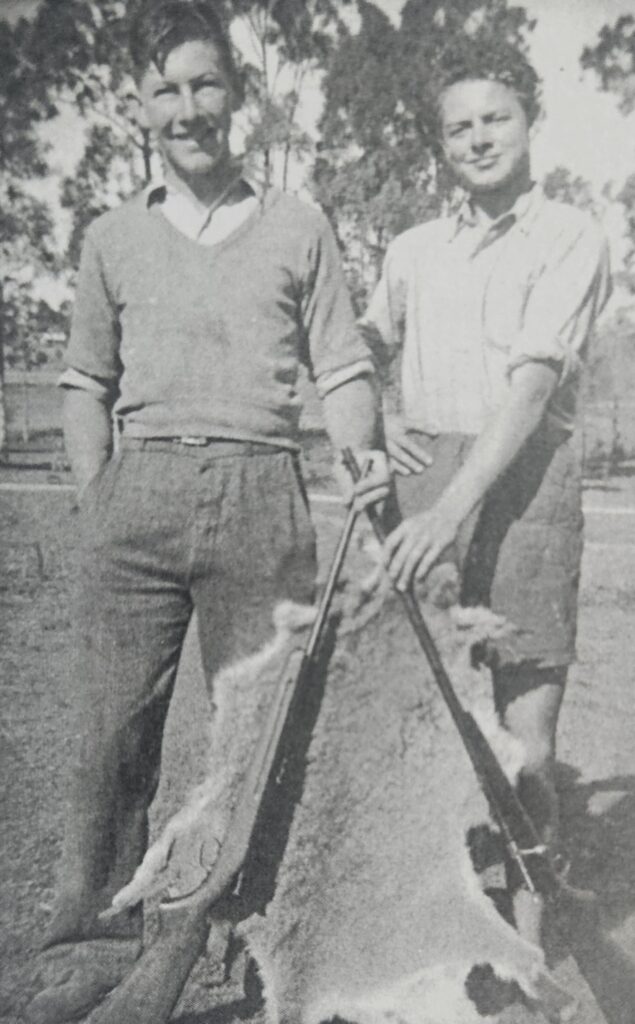

I would roam the bush with my mates and a .22 rifle, shooting anything that moved—kangaroos, wallabies—even birds (which I now regret). We would catch blue-clawed lobbies in the creeks on cotton thread, then cook and eat them on the bank. We used an old fruit tin and made a wire handle to lift it from the open fire. I remember following my uncle Jim along the furrows as he was ploughing, picking up the big white grubs. We’d feed them to the chooks, and it was comical watching them fight over this delicacy. For a time, Jim cut and sold cordwood (of a length to go into a kiln or baker’s oven). Years later, Jim delivered bread, and in the holidays I went with him. The horse was so well trained—he would just plod along the road, and whenever Jim whistled he would catch up. When Uncle Jim let me wear the coin bag, I thought I was Christmas. I liked to watch old Balfour the blacksmith working at his forge in Archerfield Road (where the drive-in was later). He made horseshoes and fixed farm machinery. He also had a big chaff-cutter.

US Soldiers

I loved to watch the US planes from Archerfield practicing “dog-fights” over Richlands. Later I joined the RAAF, and now I’m restoring an old Vampire for the Queensland Air Museum. US soldiers would come to the farm to buy eggs and chickens. They would then go and cook them in the bush. I remember a couple of times they held “chicken-plucking contests” in the yard. Grandma provided buckets of hot and cold water, and they would bet on the outcome. They also liked gambling on the American “craps”—and the “Swy” (Two-up) that the locals taught them. At other times they would pin a £10 note to a tree and try to hit it with knives and bayonets—money meant little to them. Some of these soldiers became quite good friends of my family and would visit and have morning teas with us. They were always polite, and they always brought lollies for the kids. One day, they came and rounded up all the kids (about half a dozen of us) and took us over to Wacol (Camp Columbia) to watch a baseball match. They shouted us ice cream, chocolates, and fruit, and we had a great time.

The War Ends

When the Yanks moved out, we boys would go scavenging in the bush. We would break open ammo and collect the cordite, then light it. One day, we were still collecting it when my young cousin John threw a match into the tin. It went up, his eyebrows were singed, his singlet caught alight—and I got into strife from my uncle because being older, I “should have stopped him.” When the war ended, I had just turned 14 and was working as a “floor boy” at a furniture factory on Coronation Drive (later the Coronation Motel site). The “Woodcraft Manufacturing Co” was owned by Mr. Antonioff, a Ukrainian I think. When he heard that the war was over, he came into the factory and gave us all the rest of the day off. I leapt on my bike and raced home. I was first to burst into the kitchen with the news: “Mum, Mum—peace has been declared!”