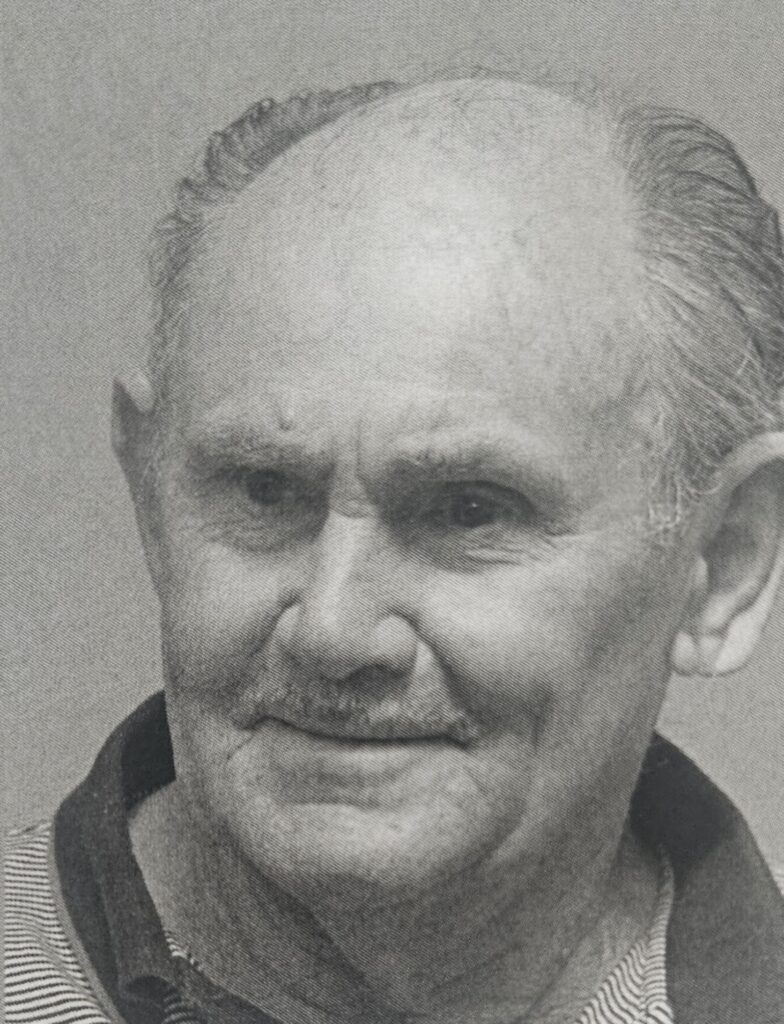

My mother’s parents were born in Australia, of Irish stock, and my father’s parents were English. My parents were married in Paddington in about 1925. I was born in Paddington in 1927, the eldest of five children. My father had a milk and ice run in Paddington and Toowong, but when the Depression came, custom dried up, and he went broke. So from 1929, our family of four traveled around the country in a horse and cart looking for work, and sleeping in a tent my mother had made. To get the dole, you had to be at least 10-20 miles from the previous fortnight’s claim, so there were a lot of people on the road. We went up as far as Monto. There was some work there, but no money. My father was usually paid in kind—flour and milk, or horse feed. We were on the road for a couple of years.

Coming to Darra

In 1933, my grandmother gave my father three blocks of land in Queensland Road, Darra. (They had bought them at the first auction of Darra Estate in 1914-15). Dad had bought an old timber house and shop in Rosalie for £12.10, and gradually he transported the bits with two horses and a wagon. I remember it cost a penny each to cross on the ferry at Indooroopilly, so my mother, brother, and I had to walk across the railway bridge to save the fare. Using this, plus timber taken off our land for the stumps, my father built us a house, then a small dairy and cow bails. We bought our first cows from Maggie Jones, because she would take 5/- down and 5/- a week. We soon bought a milk cart, and we did two deliveries a day to our customers around Darra (there were no cold rooms then—the milk was still warm). I was helping from the start—up to milk at 2 am, then deliver at 6 am, home to clean up, then milk again at 10 am, and deliver at 1 pm.

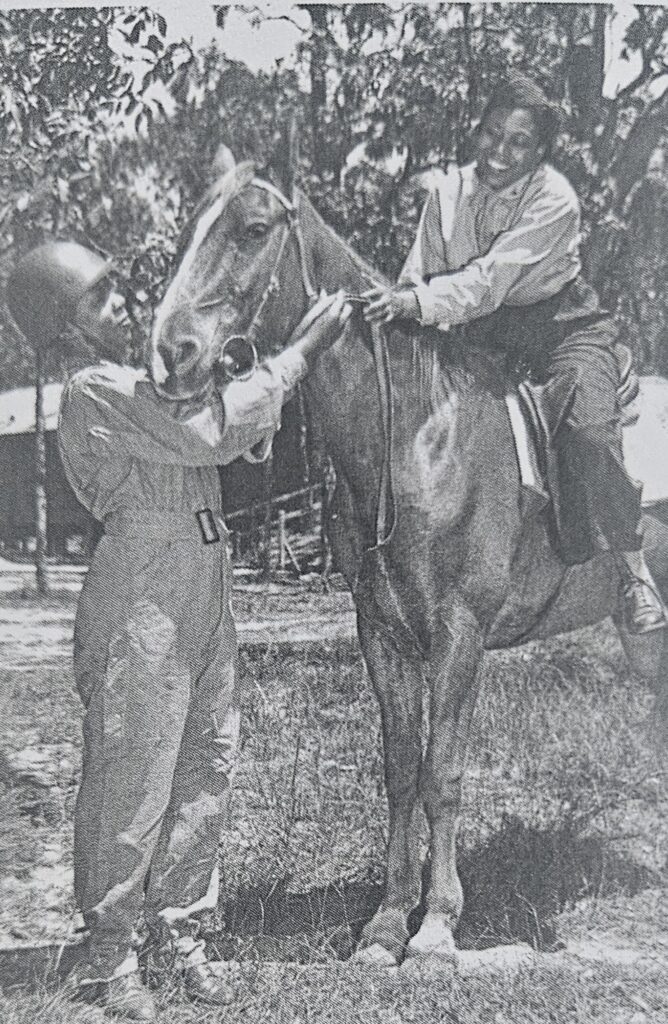

I went to Darra State School. But often I didn’t arrive until 10 am, and many days I didn’t go at all. I saw my teacher, Mr. Bourne, when I delivered milk to his house more often than at school. He was a good fellow—though Mr. Ernst and Miss Singleton liked to swing the strap. We always went barefoot—and though it was cold on a frosty morning, we could run easily down the gravel road, our feet were so hardened. I would see Bob Eason and Teddy Burgess hunting wallabies in the local bush—and they went barefoot too. The cows were tagged by BCC, so they grazed all around the area. We would round them up on a horse, with a stockwhip. We had a dog, but he would only work for my father. And generally, the cows knew what to do and when. About 1935-36, we bought another bit of land from a Darra man for just the price of the rates. And when in 1938, BCC advertised sixty-three acres, up around where Gardenway is now, we bought it at auction. Ours was the only bid, and my father paid just £1 an acre. Land was so cheap then. We had about thirty cows, though only about half were ever in milk at one time. But we did all the work ourselves.

Dairy Farms

Everyone knew the Grindles—they had a huge holding—from Wacol Station and along Wolston Creek to the river at Wacol. A large tract of their land was taken for the Americans’ Camp Columbia. I remember riding over there one day to see Jim Grindle. I came across an American sentry, and I just galloped past him. When I returned, at an easier pace, he said, “I could have shot you, you know.” At that time, much of the modern “Centenary Suburbs” was dairy farms. Goggs Road ran from Gravel Pit Road here in Darra to 17 Mile Rocks long before Centenary Highway replaced it. And Loffs Road then joined both Gravel Pit and Sumner Road. (Westcombe Road was originally Gravel Pit Road). The Sumner family had cut up their land but kept the river block for some time. Phil Hawkins bought the piece with the orchard, and he sold oranges to the locals. Snow Harrison’s farm was on the corner of Wacol Station Road and Sumners Road, down to the creek. (I remember the creek was tidal, so in drought, we would all cut water lilies for the stock). He was a good axeman, and I remember he was deaf from WWI. Snowy put down a corduroy (a track made of logs laid side by side) so the stock could get to the creek water without bogging. But he lost the use of one arm in a shotgun accident on the farm. Snowy never did much farming after that. I remember his three daughters—Mescal, Nina, and Barbara: the women all lived in Manburgh Terrace later. Fred Maurer’s farm (now McLeod Golf Course), put cattle into the Brisbane Show each year. They had a big hayshed and stored a lot of lucerne. Marrs—who had a big boarding house in Tank Street—bought the farm for their son. Alan grew sorghum for the cattle. He had two silos built from breeze blocks and put a water tank on top. The silos may still be there, on McLeod Golf Course. Jack Gibbs had one of the plots which ran from Sumner Road down to Sandy Creek. He grew lucerne on the black soil down by the creek. He had a T-model Ford, and he would jack it up, put a belt from the engine to the chaff-cutter, and then bag up the chaff to sell.

A freak storm finished him. His house was almost eaten out by white ants, and when a whirly-wind went through, the house collapsed on him. (The Crooksons lost their roof that day too). After he came out of the hospital, he stayed with a family in Darra and worked at the Cement Works from then on.

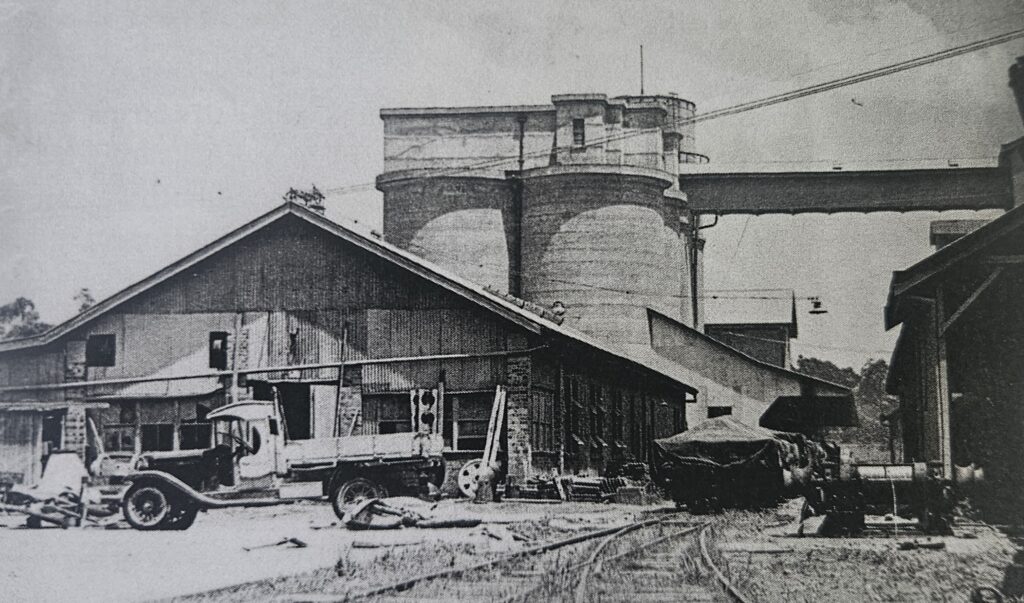

Darra Cement Works

I worked at the Cement Works too. They opened about 1916, and at first, they brought lime from Gore (down near Warwick). When that closed, some of the workers came up and settled in Darra. From 1936, they brought in coral by barge to 17 Mile Rocks. At first, trucks carted it over from the river, and huge pyramids of coral built up. I remember one day we heard screaming, and we looked across to the coral heaps. A truck had gone over the edge into the heap—and we watched its lights as it slowly sank through the pile. The Cement Works bought a strip of ground through “the lagoons” from Maggie Jones to put a direct road from the river to the factory. Years after the war, they put the conveyor belt along the same path. The Cement Works started with just two small kilns, and they ended up with six. The war brought increased output and so increased employment.

World War II

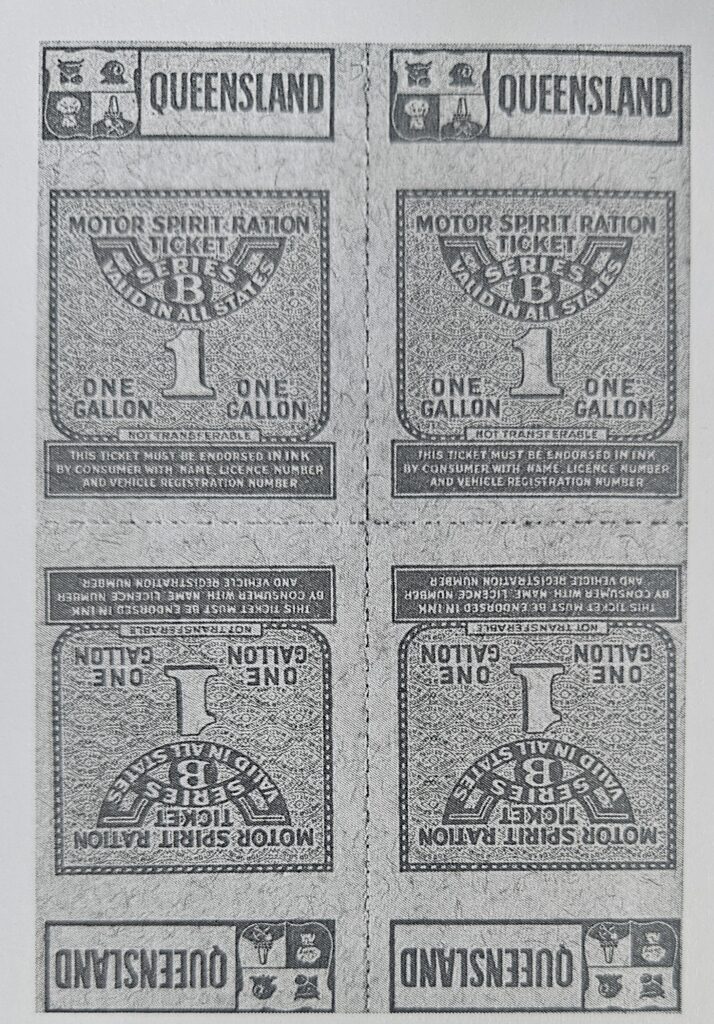

I remember everyone talking about the start of the war at school—I was at school that day. From then, we listened to the news on our crystal sets. I was glad to leave school. In 1941, on my fourteenth birthday, I started work at the Oxley Bacon Factory, working 5½ days a week for 19/6. After a few months, I had to come home to help until my father could get another lad. Then later, I worked at the Brickworks, then the Cement Works—a lot of local lads moved jobs every so often. There was more work during the war—and we could at last buy a pair of boots! But I had to go home to work when needed. Then we heard that the US Army was paying £7 a week for men to service their trucks. There was a drought at that time, the cows were dry, and we weren’t making that much between us off the farm! So both Dad and I applied and were accepted. But Manpower wouldn’t let us leave the land! Manpower also rounded up all the swaggies and sent them to the Northern Territory to build roads with the CCC. The US Army came out around here—now Gardenway to Middle Park—to train for wet weather driving. After rain, they would deliberately bog the trucks, then the soldiers would have to practice winching them out. This was all on private land—and while our stock was in the paddocks! But we decided it was OK—as long as they closed the gates. They also strung phone cables all over the area in communications training. Much of it was left behind, and I used some to make aerials for my crystal sets.

Mr. Bridgewater ran the Picture Show and the Dance at Darra Hall. He owned the hall (which was made of tin) through the war too, but I don’t know how the US Army arranged the use of it for their dances. I never went to the Army dances—there were already too many fellows—but the girls loved to go. I wasn’t off the farm much, so I didn’t see much of the Americans. And I see pictures of crowds dancing in the streets on VP Day—but I remember nothing: it was just another day’s work to me.

After the War

When the Yanks left, the RAAF moved in to clean up any remaining dangerous munitions in the Ordnance Depot over at Richlands. The CO used to live at Archerfield Homestead I think, and the men took over the camp in Archerfield Road. I used to deliver milk to the homestead—that must have been in 1946. We bought one of the first cars available after the war—a Hillman Minx made for the Army—and I delivered in that. I remember going to dances at the Homestead in the 1950s—run by the Lapidary club. They were held in an Army hut that was still there. Part of the US camp at Wacol was taken over by the Housing Commission, and a lot of returned soldiers ended up living there. There was a housing shortage after the war—and shortages of many other things too. Later (1948-49), I delivered milk to the new Serviceton settlement, where a returned soldiers group took over the US camp in Archerfield Road.