Background

In 1863, John Andrew Dunlop arrived in Moreton Bay from Scotland. Just nineteen years old, he soon found a place, clearing land along Oxley Creek for a pioneer farmer. Eventually, he became a land-owning farmer himself and grew cotton and other crops along Oxley Creek for many years.

Dunlop Park at Corinda was created from his first property “Monkton Farm” (Just prior to amalgamation into Greater Brisbane Council in 1925, the Sherwood Shire acquired and named suitable vacant land for community parks. Sherwood Forest Park was another.)

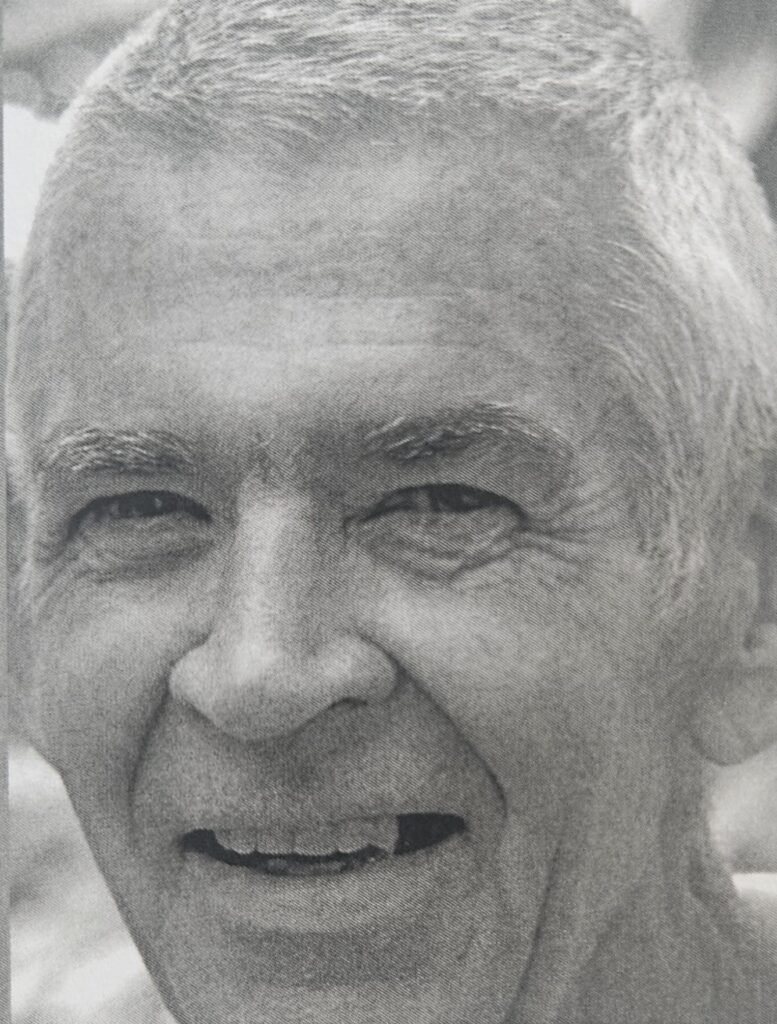

My mother’s family, the Berries, have been in the district since the 1880’s. Thus, my parents lived on adjoining properties and met after World War I and married in 1925.

WORLD WAR II

I was born in 1937, so I have no memory of the start of the war. My earliest memory is the stock reply to so many childish requests, “You can’t have/do that, because there is a war on.

All children were issued with an identity disc or bracelet. Mine was fairly soft galvanized metal, with the name typed into it. I still have mine, and it shows teeth marks. They were hung around the neck and were tempting to chew on.

Oxley/Corinda

I remember the trenches in the school yard, and the routine Air Raid drills. The Air Raid siren on the footpath outside the school yard was sounded for a test, at a particular time, one day each week. One day there was a genuine warning. We were at home at that time, and we moved into the family shelter. It was an underground shelter, dug near the vegetable garden by my father, and had a roof which had once been on a river launch, with a sliding hatch entry. I recall my mother sitting there knitting, looking just as relaxed as if she was sitting in a chair up in the house.

Later, we found out that, on that day, the hospital ship “Centaur” had been sunk off Bribie Island, and then later a plane, failing to identify itself, had led to the ensuing alarm.

There was war time propaganda. All the children were given leaflets at school. The younger ones were given a leaflet with a rhyme which began: “Johnny Jap is flying high, dropping bombs to make us cry.”

When Darwin was bombed, one of the most trusted teachers at school told us that just one bomb had fallen, and that the Australians had chased off the Japanese. We now know this was not the case. Secrecy was common. Everyone had to be careful when writing letters, and I remember my parents receiving letters stamped “Opened by Censor”-to check that they contained no information useful to the enemy.

Many of the radio programmes were war related – a lot of war time news, and daytime serials such as “Blue Hills” and “Martin’s Comer” had story lines of people going off to or returning from the War.

There was some paranoia. Rumours circulated that local Germans were sending secret signals from “The Fort” (on the river near Canossa Hospital). We had people of German descent in the community, and they were very good people, such as Karl Hoeppner, who drove the Shire grader, and parked it at the work site when it was too far to go back to the depot. When he was working on the roads nearby, we would hang around and watch for hours.

Archerfield Aerodrome

Oxley Road, with a single bitumen strip and gravel verges, was a busy thoroughfare for US convoys. They were often very long and passed the schools in both directions, many days each week. Planes from Archerfield were often overhead many hours each day.

We could hear the noise of aero engines being tested at Archerfield, and also the exhaust noise of Liberator bombers, each of which had four engines, warming up before take-off.

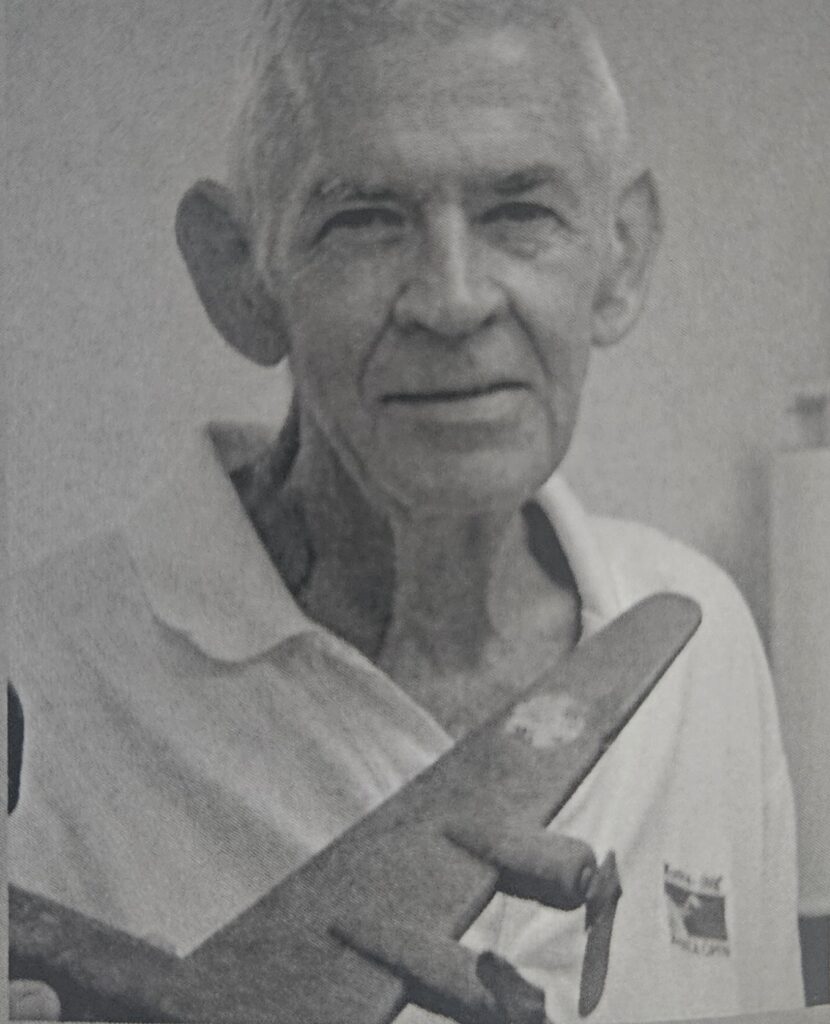

I was a plane spotter by the age of eight, always aware of the planes coming in and out of Archerfield. I could recognise Liberators, Fortresses, Kittyhawks, Wirraways, Corsairs, Avro Ansons-and there were hundreds of yellow Tiger Moth trainers. Toys were hard to get, and my father made and painted solid timber models of these planes for me, with propellers that would spin as you ran.

In March 1943, an RAAF DC3 crashed after take-off from Archerfield, into the Blunder, near Oxley Creek, and over twenty passengers were killed. All this was hushed up, as was the shooting up, by the US Military Police, of the shops at Oxley/ Blunder Road crossroads.

The Brisbane River

We lived beside the river, and were in it, on it or beside it as often as possible. We enjoyed swimming, diving, canoes and fishing. There were always war related activities occurring on the river. Sometimes we would see a line of high fronted landing barges come up the river, and they would turn at Seventeen Mile Rocks and land at Mandalay, on the Fig Tree Pocket side. Occasionally, aircraft-carrier-based fighters flew up the Brisbane River, at very low levels. Standing on the high part of the riverbank, you could look down on them; they were so low near the water.

Almost every night, we could hear dance bands, especially the saxophone, playing down the river at the Mandalay dance hall. The “Mirimar” and “Majestic,” and other launches, brought boat loads of people up to the dance hall, which was just upstream from Lone Pine Sanctuary. The Americans often had picnics on the Fig Tree Pocket riverbank, with long tables of goodies, including Coca Cola, which was unavailable in most shops.

My first Coca Cola came from one of the Mandalay picnics. We could travel over the river in old canvas canoes, and sneak things (such as Coca Cola) from the tables. I am sure the US military were quite aware of these activities.

I still have one of these old canvas canoes, which once belonged to my friends, and it had been paddled into the old Oxley Hotel during the 1893 flood! It is in poor condition now.

The Local Area

Virtually every year Oxley Road, near the present Golf Driving Range, was covered by flood waters. We would ride our bikes down there to play, and it was good to watch the Army trucks ploughing through the water.

Guy Fawkes night had always been a highlight for us. With the war, there were no crackers available, and we were too young to pinch ordinance from Camp Freeman, as some of the older boys did. We improvised. We wound strips of torn sheeting into a ball, sewing it through with twine. When it was the size of a small melon, it would be soaked in a bucket of kerosene. When ready, it would be set afire with a match, or by use of a mouthful of kero and a match. It was then thrown from person to person, caught and thrown on very quickly. Little kids and wimps (I was one of them) kicked it with their feet.

In the later War years, we acquired parachute flares from the Camp Freeman area, and emergency air strip lighting flares, which were like a broomstick. They burned with an intense light, which illuminated a wide area for quite a long time.

The Presbyterian Blackheath Home for Boys, on Cliveden Avenue Oxley, was moved to Killarney during the war, and the buildings were taken over by the US Army. The home was used for training women and was also a searchlight site for some time. The American troops going to Blackheath avoided driving past the school on Oxley Road by taking a back road, and eventually they built up such a camber on the gravel corner near our place, that they could take the sharp corner at almost full speed. They put their foot out on the running board of the jeep, to brace themselves as they went around the corner.

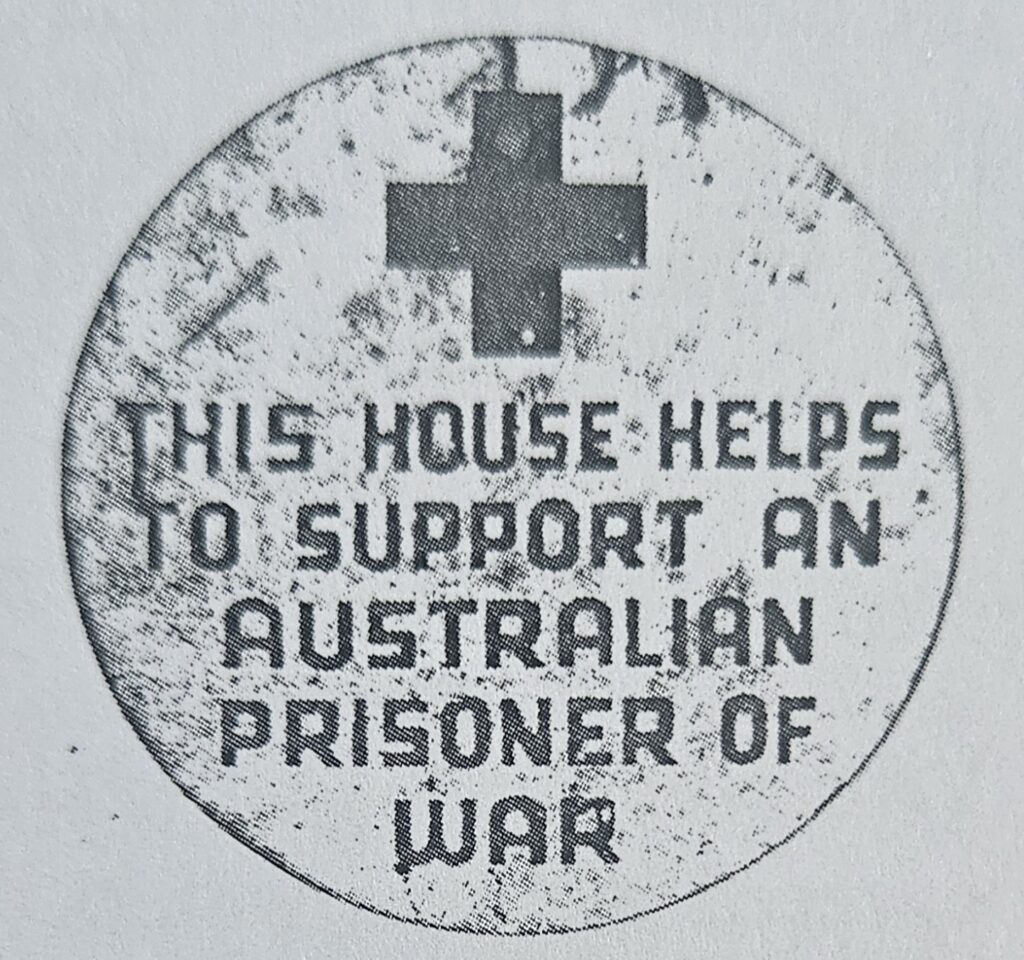

To achieve the mandatory blackout, some of our windows were painted black, where the curtains were inadequate, and the car lights had hoods fitted that looked like top hats. At our letterbox was a metal Red Cross badge reading “This house helps to support an Australian Prisoner of War.” We had ration cards for clothing, meat and petrol, and we produced our own eggs, mangos, custard apples, persimmons, mulberries, bananas, cabbages, and other home-grown vegetables.

My father was a local Air Raid Warden. He was a gas victim during World War I in the Somme campaign, and he was amused by the grave warnings issued at the meetings of the Air Raid wardens, by people who had not been exposed to shell fire and gas and had no real understanding of combat conditions. I still have his ARP helmet, which was once white. The other equipment, I remember, was a Gas Alarm clacker, a very long handled rake to push sand over smouldering material, and a tubular whistle.

Almost every man smoked in those days, and so did my father, even though his lungs were gas affected. Usually, his cigarettes smouldered away on the ash tray, with just one puff at the beginning and at the end. Australian cigarettes were preferred, mostly Capstan. American cigarettes were said to splutter and had a different smell. My mother smoked also and rolled her own with ready rubbed tobacco and Tally Ho cigarette papers. Serious smokers preferred Log Cabin flake cut tobacco, which had to be rubbed before it could be made into a cigarette.

Camouflage Net making

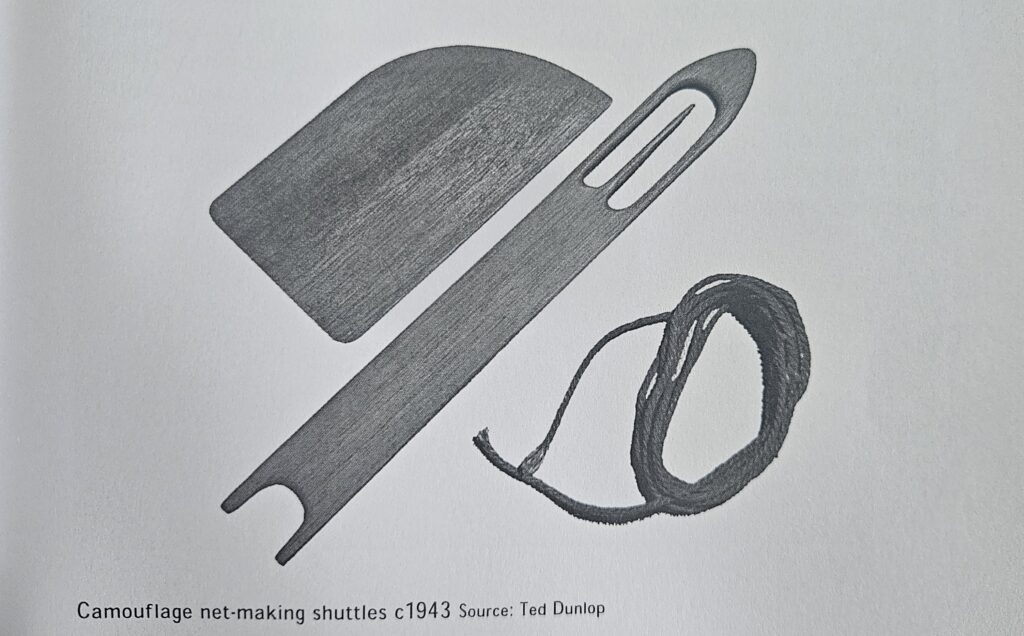

There was a national project for making camouflage nets, and my mother became the local Secretary. The volunteers met in the Scout Hall, and took great pride in their work, as though they were knitting for a competition. Nets could be as large as 29 feet square, and the final inspecting ladies could detect one loose knot! 420 nets were produced by the Sherwood group, to replace those that had been blown to bits during combat.

The first group of nets was made with a smooth linen twine, but later during the war, around the time of the Coral Sea Battle, they were changed to being made with sisal cord. The object of this was to provide a net that could be hung from the side of a boat and allow a handhold for survivors. The rescue boat could then move slowly through the water and avoid stopping-when they would have become a sitting target.

This sisal was harsh and hairy, and cut into the hands of the net makers, and was very unpopular with them. They wore their “Net Makers” badges with pride, and were critical of those who would not volunteer to help, because they were “too busy”.

Oxley/Corinda

I would go to the netting hall after school and get a ride home in the car. The rolls of twine and sisal had to be transported by car, and enough petrol was found for that task. It was not possible, however, to get permission to buy a new battery, so the ladies had to learn to wind the crank handle, to get thp.ear to start.

The netting hall was near the railway line, and at times a troop train would stop, and the ladies would rush around trying to provide cups of tea for the hundreds of soldiers hanging out of the windows. The men would be laughing and “chiaking” (showing off) because of the impossibility of the task. The ladies would rush up the steep embankment, but only manage to get a cup of tea to a few men each time.

Many years later, my mother was awarded the British Empire Medal for her community work, including those duties carried out during the war years.

After the War

I was eight when the war ended, and I remember on VP (Victory in the Pacific) Day, standing out on the road. We could hear the Blackheath Home boys giving three cheers. My older brothers went into town for the celebrations in Queen Street.

Convoys began carrying aeroplanes, with their wings removed, along Oxley Road. These aircraft were carried out on barges and dumped in Moreton Bay.

Rationing continued for years. Food and clothing rationing eased before the petrol rationing. There was a great shortage of building materials for some years.

Disposal Sales of military equipment were held. My family bought a very heavy army tent and fly (second tarpaulin). This was used for holidays for many years after the war. Mother also bought a bright yellow parachute, which had been coloured this way to have high visibility after a pilot had to ditch into the ocean. This was laboriously unpicked for a supply of silk material for dressmaking.

Even now, some remnants of the war years remain. The Oxley CWA building is an army hut from Camp Muckley, which was over near Archerfield at Acacia Ridge.

During the war years, in late afternoon, there was a radio serial called “Search for the Golden Boomerang”, which kept me glued to the radio. It was sponsored by Hoadley’s Chocolates, who made Violet Crumble Bars-“But you will have to wait until the war ends, because all our production is going to the troops.” After the war, I did get a Violet Crumble Bar. They were very expensive, nearly a shilling I think, so it was cut up into small pieces, to be eaten slowly, in true wartime austerity style.